A Brief History of Boise

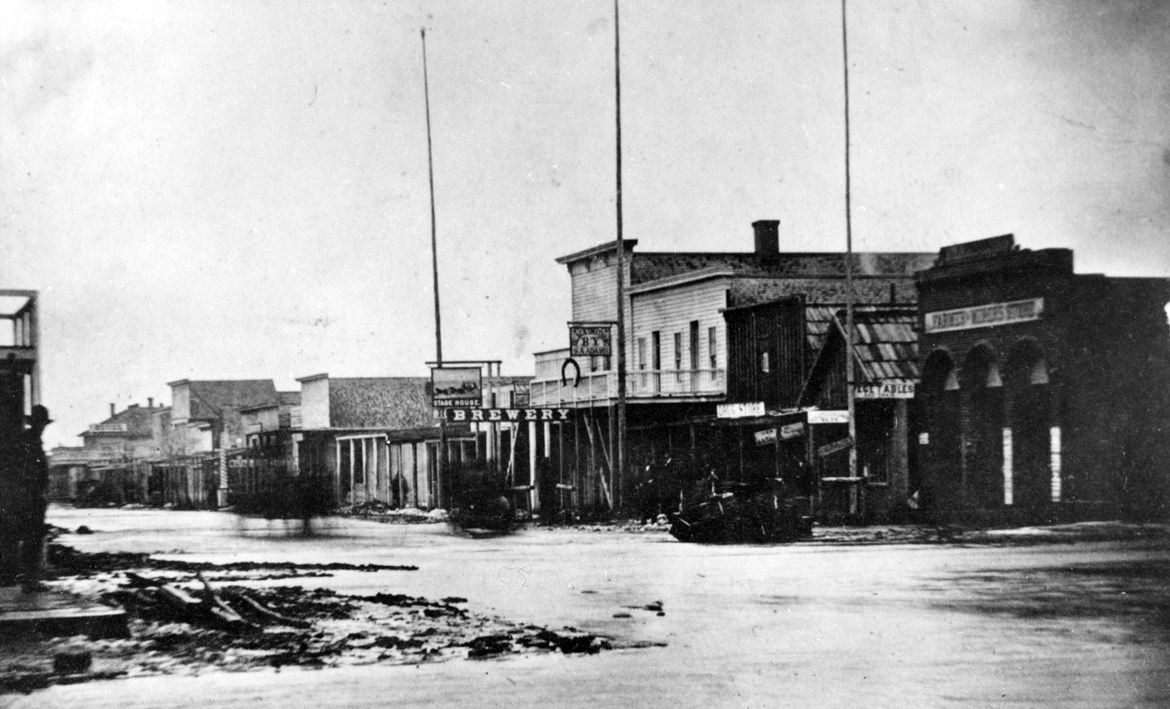

Boise, Idaho. Looking west from 6th Street circa 1866. Idaho State Archives, 65-132-6.

Overview

The city of Boise sits at a unique crossroads. Established in 1863 along the Oregon Trail, the city exploded out of the high desert, and has witnessed a long history of dynamic change and community growth. While Boise was first built and settled by pioneers, miners, and entrepreneurs from around the world, this landscape has been home to humans from time immemorial. A broad and rich tapestry of cultural and ethnic identities have been represented throughout Boise’s past, and preserving this diverse history is crucial to creating a more welcoming and inclusive community into the future.

Indigenous encampment along the Boise River circa late 1800s. Idaho State Archives, 62-86-7

Indigenous Peoples of the Boise Valley

For thousands of years, indigenous people occupied the Boise Valley and Snake River Plain in southern Idaho. Bands of Northern Shoshone, Bannock, and Northern Paiute people lived in these areas, migrating with the seasons, and following food supplies and other resources across the region. The Boise Valley was an important gathering place, particularly for the Shoshone, who migrated there in the autumn for salmon spawning and made their winter encampments. On the east end of the valley near present-day Table Rock, indigenous people made ritual use of the geothermal springs and buried their dead in the hills above the plain. Today, Eagle Rock Park (f. Castle Rock), is a central part of an annual gathering known as The Return of the Boise Valley People, where descendants of the original inhabitants of the valley meet to share stories, traditional foods, and honor their ancestors.

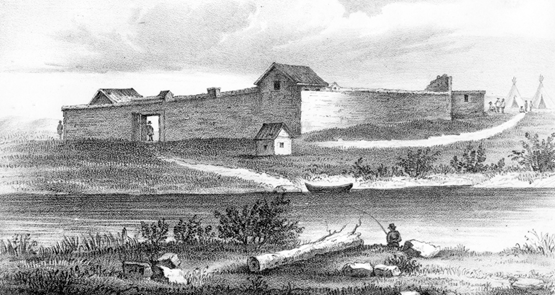

Lithograph depicting the original Fort Boise established by the Hudson's Bay Company near current-day Parma. The fort was abandoned in 1855. Idaho State Archives, 1254d

The Arrival of White Settlers, 1811-1860

In 1811, an expedition of white explorers entered the Boise Valley, and soon fur trappers and traders flocked to the area. Inspired by the sight of the tree-lined river cutting through the high desert, white explorers named the region for these woods. Labeled “Wood River” by native English speakers and the “Boise River,” by the French, the French designation stuck by 1834, when Fort Boise was established near the confluence of the Snake and Boise Rivers. This (nonmilitary) outpost supported fur trappers and traders, and by 1840, Fort Boise was a vital stop for travelers on the Oregon Trail needing food and other supplies. Increased traffic along the Oregon Trail led to more contact and more conflict between indigenous tribes and white settlers. The United States responded to tribal/indigenous raids against Fort Boise, fur traders, and wagon trains with military retaliation, particularly after gold was discovered in the mountains and sparked a frenzied rush of people into the Idaho territory.

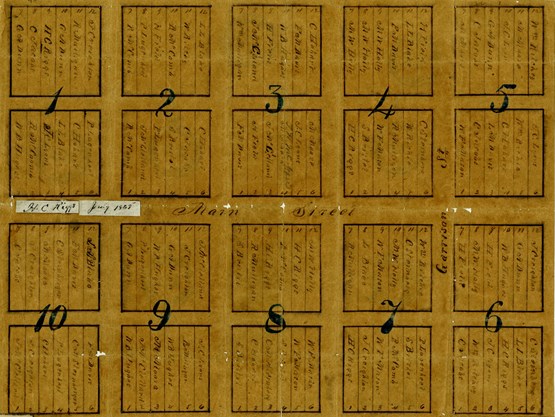

Boise’s original plat, drawn in July 1863, included ten blocks centered on Main Street. Idaho State Archives, G4274.B63 1863.R45

Gold, Grit and Growth, 1860-1863

In August 1862, explorers struck gold in the mountains above the Boise Valley, about 25 miles northeast of the future Boise city. Within months, thousands of people descended on these gold claims and built mining towns nearly overnight. In the Boise Valley, merchants and entrepreneurs followed the overwhelming demand for supplies and set up businesses to support miners and ship food, equipment, and other materials into the mountains.

Sensing the potential for rapid growth, a group of businessmen met on July 7th, 1863 to organize a small town they called Boise City. They set aside plots of land along what is now Main Street between 5th and 10th streets, and designated parcels of land to construct public buildings. Sandstone was quarried from the base of Table Rock for construction and by the fall of 1863, Boise City had over 700 residents, with the promise of many more to come.

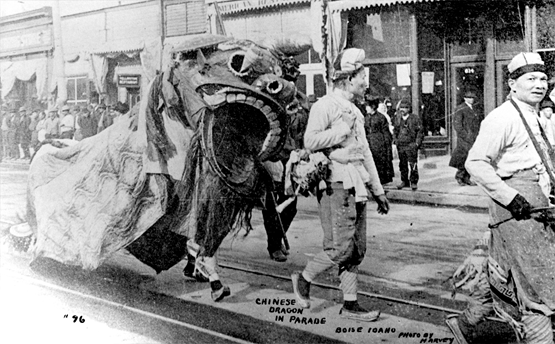

Dragon in Parade, circa 1900's Boise, Idaho. Idaho State Archives, P1979-148-2. Dick d'Easum Photography Collection.

Faces of Change

Once Boise City was officially established in 1863, and with a gold rush underway in the Idaho territory, the US government dispatched soldiers to remove Native American people still residing in the Boise Valley. A combination of vigilante forces and military efforts pushed indigenous people into the foothills or away south of the town. Outbreaks of measles and tuberculosis killed hundreds of people, and in March 1869, US military forces marched the remaining indigenous people to Fort Hall, in eastern Idaho, and the recently established reservation there. Today, the city of Boise still stands on the ancestral, cultural, traditional, and unceded territory of the Shoshone, Bannock, and Northern Paiute people.

Boise continued to grow and change as people from around the world moved to the new city hoping to strike gold or to capitalize on business opportunities that arose alongside the mining industry. Census records show boarding houses full of people from the Basque County, Central America, Japan, and eastern Europe within a few city blocks. In 1870, Chinese people made up over a quarter of Idaho’s population, and Boise saw the development of not one, but two different Chinatowns. A broad and rich tapestry of cultural and ethnic identities have been represented throughout Boise’s past, and preserving this diverse history is crucial to creating a more welcoming and inclusive community into the future.

Destruction of the Hip Sing Tong building during Boise's urban renewal era. Idaho State Archives, 72-100-90/Q.

Balancing Progress and Preservation: Boise Urban Renewal

Boise has grown and changed dramatically from its founding, but much of its historic landscape has been lost. During the 1970’s, many downtown buildings were demolished to make way for new businesses and surface parking lots. Urban renewal, or the process of reviving or modernizing cities, targeted many of Boise’s diverse neighborhoods, resulting in the destruction of Chinatown, the redevelopment of the River Street neighborhood, and the near-total loss of residential architecture along Grove Street. Small parts of the Basque District, and some iconic landmarks including the Egyptian Theatre were saved from demolition. Today, through preservation, public art, and collection efforts, the City of Boise works to reconnect residents with many of these lost historic and cultural spaces, to foster a greater understanding and appreciation of the diverse community that built and sustained the city for generations.