Creators, Makers, and Doers: Adam Rosenlund

Posted on 11/16/16 by Arts & History

Adam Rosenlund knew from a young age exactly what he wanted to do: create comic books. While that passion continues to blossom, Adam augments his career as a hired gun for various kinds of illustration work. His bread and butter creating illustrations for national and international business entities provides him stability, and he spends the rest of his time focusing on personal comic projects. He and co-collaborator, Ethan, will soon celebrate the publication of their first book, published by Dark Horse Comics.

What is your primary creative output?

I would say illustration and comic art.

Do you prefer one over the other?

I think my passion is for comic art, but I make the most money off of illustration. The commercial side tends to be more illustrative and then the passion comes from making comic books.

Are you working on any comics right now?

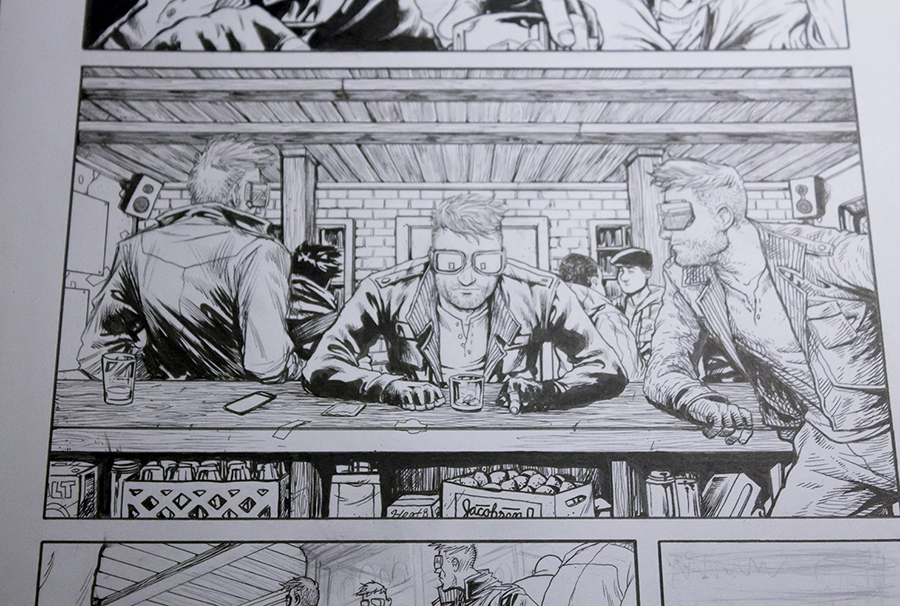

I have a Web comic. It hasn’t been updated in a while, but that’s mostly because of work, actual paying jobs that get in the way. And then currently, I’m actually working on a book with my friend Ethan. It’s been a long time coming, but we’re working on a book for Dark Horse Comics. I believe that’s slotted for summer of next year. The lead times on those tend to be really big. For comic stuff, that’s kind of what I’m doing right now. And, doing that has kind of slowed the output of the other stuff that I can turn around super-quickly. I haven’t actually been able to make a lot of actual comic books that I put out there in a little bit because of that and the other work, but once that comes out I think the flood gates will open and you’ll see all the other stuff I’ve been working on in the meantime.

Where does Dark Horse fit in the comic book industry?

They’re one of the top publishers, especially on an independent level. They don’t have the output of Marvel or DC, but they’re like an Image Comics style place. The deal that we have, Ethan and me, we basically retain ownership and they just put the book out for us. So, it is really nice. They’re great to work with. They’ve made books like, Hell Boy and Sin City. So, they kind of started with the idea of having creators in mind, so they can own the properties that they create. They do some licensed stuff as well. Up until a couple years ago, they had Star Wars stuff. They do all the Aliens and books like that. They have some licensed properties, but the most popular stuff that they put out is definitely their creator-owned books.

How did you get your start in comic books?

Since I was five, it’s basically the only thing I’ve wanted to do. It’s the only thing I’ve really worked toward as a career option since I was very, very young. Even if it wasn’t exactly comic books, I would hopscotch between that and wanting to be an animator and wanting to do plain illustration. I went back and forth between that and comic books, and never really wanted to do anything else. So, I set my mind towards that as my goal and just pursued it all the way through. Professionally, I would say I’ve been doing comics and illustration since junior year of college, which was 2004 or 2005— I don’t know— a long time ago. That’s basically when I started pursuing it and trying to build a book of clients and actually put myself out there in a professional manner, not just drawing my silly little funny books and stuffing them away in a file somewhere.

What is the genre or style that you create your comics in?

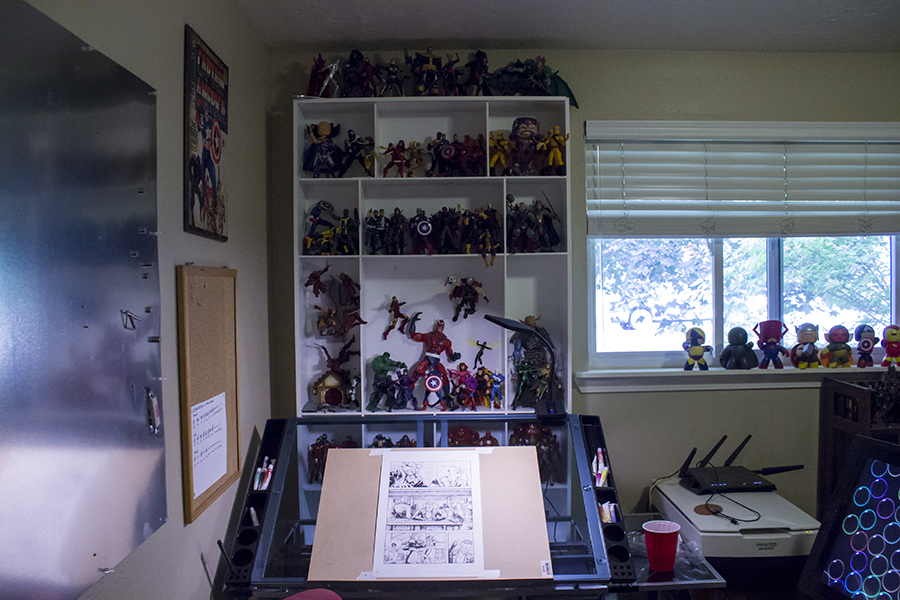

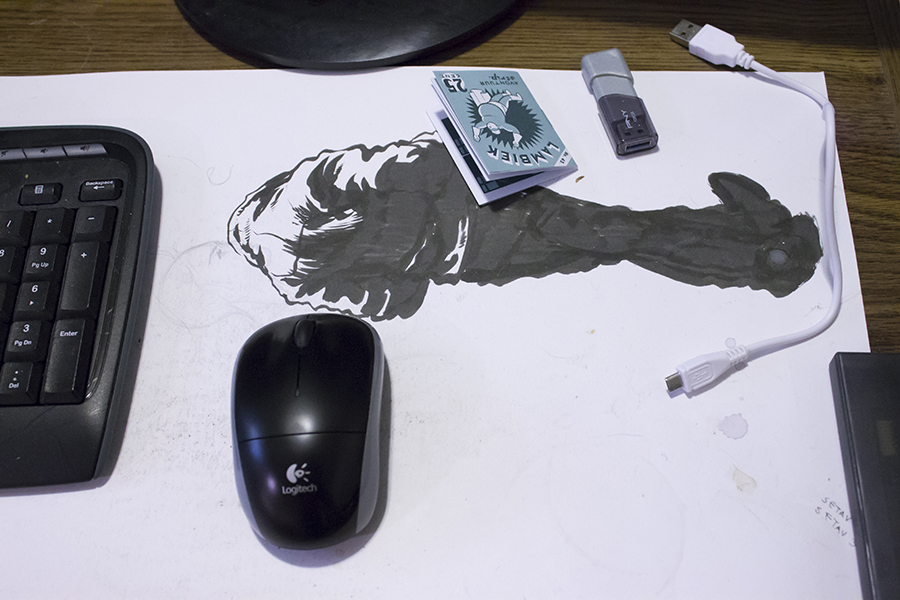

Mainly what I do is science fiction. A couple of the books that I’ve been doing with my collaborator have a cyberpunk focus. We were very heavily inspired by French and European comics from the ‘70s and ‘80s. It has a very unique aesthetic and can parlay in both fantastical, silly subject matter, but also be very serious books as well. I mean, I still like Spiderman, X-Men, and Captain America, stuff like that, but I think the stuff that gives me the most creative reward is the science fiction questions. We tend to ask ourselves a question about current society but extrapolate it thirty or forty years into the future. Plus, it’s just a hell of a lot of fun to draw that kind of stuff, like robotic eyes and cyborg lenses and that kind of stuff. I like getting a bunch of little mechanical details and things like that, stuff that will give you carpal tunnel syndrome if you’ve been drawing it for too long. That’s the stuff that really is fun for me, really fulfilling to draw. So, I tend to just lean into it.

For the comics, do you do both drawing and writing or do you just focus on the drawing?

I mostly focus on the drawing. I’ve been lucky enough to find my friend Ethan, who also wanted to pursue comics, but he is more focused on the writing aspect than he is with the drawing. We share the same brain in a lot of ways, about what inspires us creatively. So, finding him was an amazing opportunity, so we collaborate together. We come up with story ideas together, but he’ll do the scripting phase and I’ll execute based on that script. Luckily I’m not just a hired gun on a lot of those projects, like you can be with some of the other type of work. If you’re working for Marvel, a lot of times it’s like, “Here’s your script. Try to stick to it as best you can.” You don’t really get that same sense of, “This is mine, I created this thing whole cloth.” But, with a lot of the work that my buddy and I are working on, it feels like a 50/50 split. It’s as much my baby as it is his.

Can you talk about your illustration work? Is that how you make a living?

Yes, for the most part, but it widely varies. I do work for video game companies. I do editorial illustration. I do work for record labels. I just finished a job for the Grammies and an album cover for a talent search band award-winner, which was kind of an interesting project. It’s all over the map in regards to illustration. That stuff, I would say, is probably more hired gun type work. Lately, I don’t have to pursue that work. That type of work that comes to me is right in my wheelhouse. I’ll get a cold e-mail from somebody saying, “Hey, we love your stuff. We have this concept in mind and we thought you’d be a great fit for that. What do you think?” Then we work out the details from there. Luckily, I haven’t had to do much in the way of, the hustle, in a few years, because usually within two weeks of a project ending, somebody else is e-mailing me about starting something. Hopefully I can just keep going down that path as long as possible, because I always feel like the hunt and the business aspects of a creative job is the kind of a thing that causes you to lose interest in that job relatively quickly. So, luckily, I haven’t run into that issue in quite a while and I’m able to concentrate on making cool stuff instead of doing the nitty-gritty details of trying to hunt down work and that kind of thing, which is never fun.

When you’re working in both illustration and comics, do you still work on paper or is it mostly digital now?

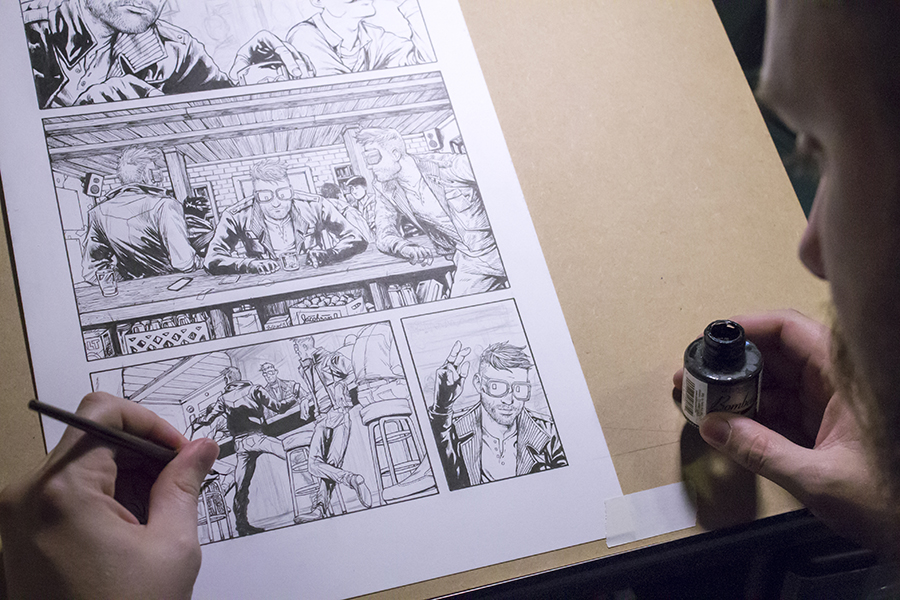

For illustration, I would say I’m mostly digital now. I’ll do elements on paper, but usually I’ll just scan those in to use as an element in the digital piece. For some reason, for comics, I need to have a comic page. I need to have an eleven-by-seventeen piece of paper with all the ink done by hand. For deadline purposes, I probably shouldn’t be so precious with it because it’s a lot of the waiting game and fixing mistakes takes a lot more time there than it does on the computer. But, I like having that tactile thing at the end where it’s like, “This is everything, it’s the whole page, here it is”—instead of it just being a file that exists on my computer. I’m not that precious with it when it comes to most of the illustration stuff because I think it’s probably that differentiation between, “I’m working on this, it’s work.” Even if I like it versus, “This is my thing.” So, I like to have an end product with the comic because it’s mine. If it’s just a client hiring me to do an illustration for an album or something, I’m not as precious with it, so I’m more than happy to just do it digitally. Plus, it makes the revision process a lot easier for them. If they come and say, “Oh, we need to tweak this,” instead of having to gesso over the eye or something and fix it and then repaint it, you just fix it digitally and take five minutes.

Can you elaborate on the divide that happens in your work between the physical process and the digital? Do you enjoy working digitally?

Yes, I do. The way the tools have evolved, I have one of those monitors that you can draw on. And, between buying and creating a breadth of brushes, I feel like you can do so much with a very small impact on your work area. I can make oil paintings, gouache paintings, pen and ink, and ink wash digitally and it’s just all right there, nice and clean. The feel of it’s good. The feel of actually making it feels, not one-to-one with actually doing it physically, but close enough that the pen stroke has satisfaction to it. But, there’s still something not quite there with it.

In regards to comics, it’s that tactile thing, you can feel your hand rubbing against the paper, you feel the smudges, you have ink on your hands at the end of the day. It feels more worked. It feels like you smithed something, like you made something and you have a thing to show for it. It’s not just a bunch of ones and zeroes sitting on a hard drive; it’s a thing that will live forever or be lost to the sands of time.

Is creating the physical artwork more prevalent in the comic book world?

I think it is just a matter of tradition, but I think that’s eroding away. A number of comic artists that I really like a lot don’t work on paper unless it’s something that somebody buys or something that they specifically want to keep or get a specific effect out of. A lot of people are just moving to digital because it’s quicker. You can probably get more done with less effort. In a lot of ways, in the comic industry, it is a very tradesman art form, especially if you’re just doing work for hire. So, the person at the end of the line that’s handing you the check for making this book doesn’t care how you get to the finish line as long as the finished product looks good. They’re making the book and they’re selling the book. They’re not selling your art.

What are your opinions of the comic book community here in Boise?

It’s growing like crazy. If you see the Library Comic Con, people are there—a lot of them. I think the opinions from the industry that Boise is a place where people create comics is growing. Chris Hunt just put out his first full book and it seems to be doing very well for him, getting a lot of traction through mainstream press and everything like that. I think everybody’s very supportive. There’s not a lot of backbiting that happens. In larger comic communities it has the same old effect that most communities have where this guy doesn’t like this guy or this problem happened between these two people or these two groups of people. Boise’s just inherently positive when it comes to comics. That could be an issue of it being very small, so, it’s like, why hate on anybody? We’re all a community here. We’re trying to bring comics as an art form to greater popularity in the community and, honestly, it’s a great place for any comic artist to live, because—especially in Boise, it’s like this oasis of arts and culture in the middle of Idaho. Especially being a free-lancer, your money goes pretty far here in Idaho versus living in New York City or one of those other metropolitan areas. You lose a little bit of that larger arts world appeal living in a place like Boise, but I wouldn’t trade it for any of those other places.

So there is a community of comic book makers here?

Yeah, and it’s growing all the time, and I think it’s especially prevalent with kids. A couple years ago, we taught a class to kids about how to make comics for the Boise Art Museum. There was twenty, twenty-five kids in there. They were all just ecstatic about the idea. If you have a story, you can turn it into a comic. The nice thing about comics is you don’t have to wait the way you do if you’re making a movie. You don’t have to have actors, you don’t have to have a budget, you don’t have to have special effects. If you have paper, if you have a pen or a pencil, you can make any story you want, as big or as small. You can make a galaxy-spanning epic or just a story about a guy who had a bad day at work, going home to make soup. You can tell any kind of story, as big budget or as little, in comics. So, I think the appeal is there, that you can get your story out there in a very short amount of time with not a lot of, I wouldn’t say without a lot of effort, because obviously making comics can be difficult, but it can come fully formed to the public. There’s not too many cooks in the kitchen. It’ll just be you, your idea, and whether people accept it or not, it’s out there.

Are there any resources missing here that could help the comic book community be more successful?

It’s hard to say. I wouldn’t say there’s anything missing. I think it’s just a matter of size. A place like New York or L.A., it’s a massive city with a massive art community. In Boise, it’s just a matter of time, really. The community has to grow, and especially niches within the community. There’s the greater arts community and then there’s the illustrators or the comic artists. Just as the city grows and as interest grows, I think everybody will rise in the tide with it. But resource-wise, I mean, honestly, if you’re an artist coming up in Boise, I would say you have more opportunity to make a name for yourself, at least within the community, than you do in those larger cities. You’re not just a pebble on the beach, you actually matter here because there are fewer peers and there’s fewer people competing for everybody’s attention in Boise. If you want to be more nationally or internationally renowned, getting your start here, you have a greater opportunity to get in front of people that can be an ambassador for your work. It’s a lot easier here than it is in a larger market. I think people, if they poo-poo the idea of trying to be an artist in Boise, they’re not thinking it through well enough. There might be something to be said if you’re looking for a variety of artists. I didn’t go to school here in Boise, I lived in New York for a while, but Boise’s actually been a great place.

Finally, do you have any words of advice for other illustrators or aspiring comic book makers?

The most important thing is to just draw and make stuff. Even if it’s bad and you know it’s bad and you feel in your heart of hearts that it’s awful, make it, get through it, throw it away, and make the next thing. I think the old adage in comics is that everyone has to get through a thousand awful pages before they make a good one. I honestly think that’s right for any medium. You have to work your way through. It’s all a learning experience, and it’s all learning experiences for your entire life. There’s always new things to learn when it comes to creating comic books, so, just do it. Even if all you have is copier paper and Bic pens, you can make a comic book.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History.