Creators, Makers, and Doers: HomeGrown Theatre

Posted on 12/20/17 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton ©Boise City Department of Arts & History

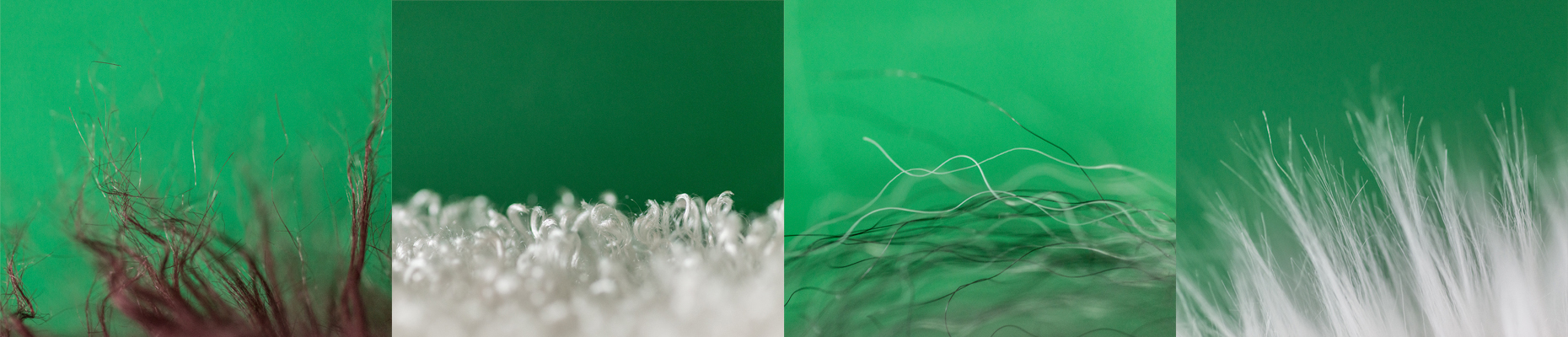

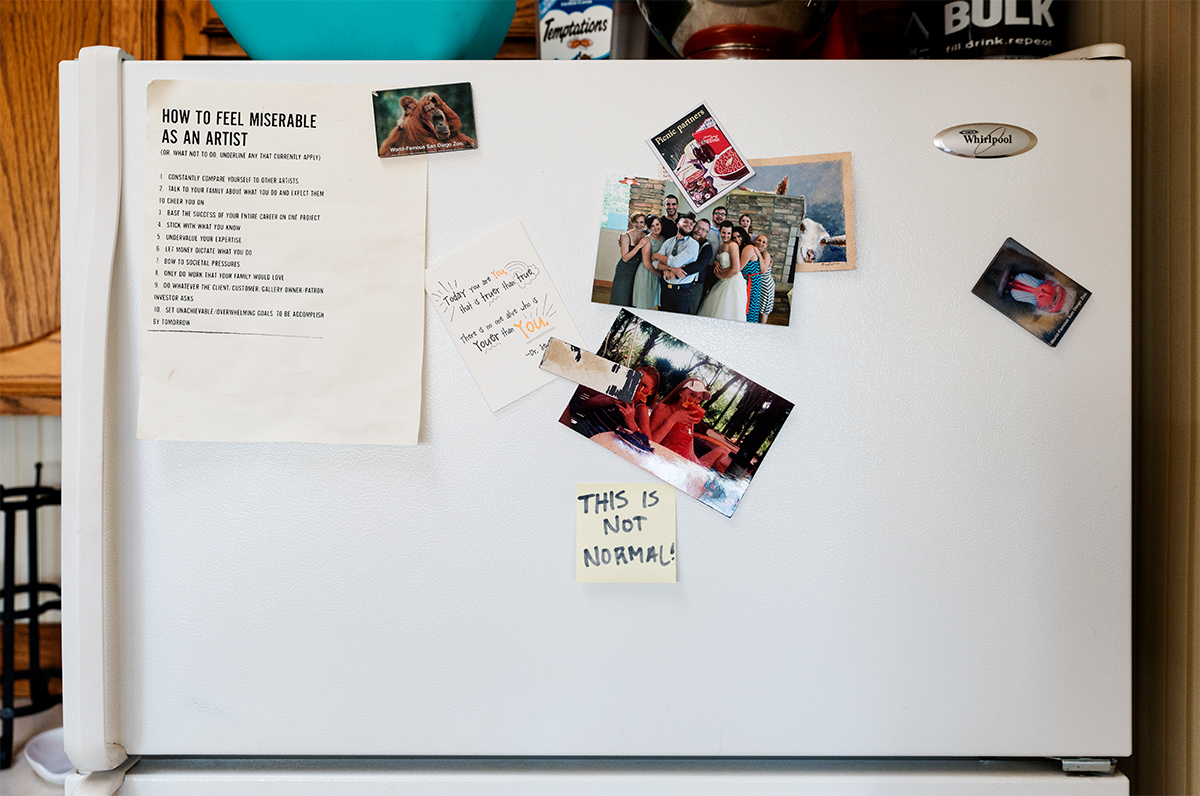

HomeGrown Theatre is a local small production company directed by Chad Ethan Shohet and Jaime Nebeker. Together they work with a talented team of performers and production crew to write scripts, craft puppets, and produce a yearly event called the Horrific Puppet Affair. Days are spent designing props and puppets, including elaborate shadow puppets in a garage/workspace, and nights rehearsing in the basement of the Gem Center for the Arts (sometimes while under construction.) Their mission is to serve an audience of peers, a group that seems to have fallen between the cracks when it comes to performing arts. HomeGrown rises to the challenge by bringing the show to bars and alternative venues, drawing a crowd who comes for the beer and laughs, but stays for the smart, real storytelling.

So we’ve been talking about peers and we need to figure out which generation you are, or we are, because there’s X, Y—and then—

I think technically we are Millennials. I think if we Googled it, Millennials are born after 1980 through 1998.

I am not sure if I am a Millennial, even though ’80 is my birth year. [note: I have since been told, by a Millennial, that I am not one.]

But Millennial “It’s such a dirty word.” Yeah, “Millennials and their phones.” I think the current generation is always [stereotyped as] the laziest and worst generation, as told by older generations—

It seems that way sometimes. Have you been told that?

We got called out, we were on a camping trip. Jaime and I had gotten in our car and we just drove and drove and drove, and that’s how we tend to travel. Because we also never have time, and we realized we had a day off. We never have time to plan, we just, [whoosh,] go. We were in some small town in Oregon at some bar, looking for a place to pitch our tent, we’re on our phones looking for nearby campsites, and some jerk comes up and says, “You Millennials, always on your phones. Get off your phones and live your life.” And we’re, “We’re so spontaneous!—what are you talking about? We have no plan. We’re hundreds of miles from home. What more do you want? We are living life, we promise you. We just need to find somewhere to [camp.]”

How do you think Millennials feel about theatre and performing arts?

I interned for BCT [Boise Contemporary Theater] for a while and I would go out to Art in the Park type events and pass out flyers. I continued to notice a trend where folks—people in their fifties and sixties, would be, “Oh, yeah, I’ve got my season subscription. I know what this is.” And people my age had never heard of it before.

Why do you think that is?

I helped with productions, and kind of in those early years we didn’t really have a voice. I was starting to get really passionate about the voice that we should be and the kind of plays that we should be making and the kind of audience we should be making for. Why is it that something I love so much is something people my age don’t go to? I would spend time going to Neurolux and to whatever random concert, sitting on the patio and people are ready to spend ten dollars for a band they’ve never heard before then another twenty dollars at the bar and sit outside on the patio the whole night [not really listening to the band.] But they won’t go to the theater because it’s too expensive and because it’s not being made for them. We wanted to say, “Cool, well, you actually do love this—you just don’t know you love this, yet.”

So you started writing and producing original material because of that vacancy?

Yeah, the same people who would hang out at Neurolux would come to us and affirm it. They’d say, “I didn’t know that this could be for me. I thought this was going to be, like, a sketch thing or whatever, something dumb.” And we really tried to make that part of our play. We start really silly, then hook them with something more emotionally fulfilling—and something that fulfills a theatrical experience that they’ve never had before.

I’ve just seen the Horrific Puppet Affair and I’d have to agree. The content is real, edgy, and relevant while at the same time being creative and fanciful. And it’s just straight up as funny as—heck.

Yes, that became essential to our mission.

You saw an entire generation missing out on live theater and you thought, “I can do this”?

Yeah, without a doubt. Because we know what’s interesting for us. And we’re not for everyone.

What does your audience want?

Well, they don’t want “Annie Get Your Gun.” No. [Laughs] Our audience is incredibly smart and they don’t want to be talked down to and honestly, they don’t want to follow our lead. They’re kind of, “Screw that!” a little bit; they want to go on their own ride, on their own terms, on their own time. I just have to learn to tune into what my interests are and trust that and find a way to tell an interesting story as far as our original content goes. It’s tuning into what we’re excited to see, and then as we’re making it, continue to listen to that voice.

What’s a good example?

I mean, “Puppet Affair” is the most bug-wild thing we can imagine.

You mentioned the Puppet Affair is not for everyone. Who is it not for?

You know, someone who is sensitive. We generally [use] profanity, we don’t censor ourselves a lot. For last year’s “Puppet Affair,” Boise Weekly said there’s some trigger warning pieces, that we were making light of darker content.

Did that surprise you?

JN: I think there’s a difference, [depending on] how you’re seeing it, right? I built a piece about body-image issues; this puppet of mine, which was almost my full height, was seeing all these images of people with blue eyes and wanted blue eyes, so she tried to tattoo her eyes, and she was seeing people with curly hair and so she tried to electrocute herself. And she wanted to be taller, so she cut off her leg. It was a body horror/body-image piece. These are things I wish I could let go of, like, “What do people think of me?” It goes back to that judgement thing, something I’ve struggled with a lot. Especially as an actor.

“You don’t have enough this, you have to much that”?

But because it’s during this night of [farce] jokes, maybe people are misunderstanding—thinking that I’m making a big joke of it.

But it’s coming from a very real emotional place?

JN: Yes. It’s a horrific “Puppet Affair” and that is my horror.

CS: [We] juxtapose horrific events with comedic moments, because oftentimes that’s how we as animals listen.

I think so to, isn’t that interesting? It’s a balance, looking at real issues while also entertaining, but understanding these are serious issues.

But get them laughing [first.] The dangerous part is when you have sarcasm and subtlety ride that fine line; when there are people in the audience who don’t see that joke as sarcastic. People who are then laughing with the [obtuse] characters instead of at them [as intended,] it [potentially] makes people whose experiences do not reflect my own feel vulnerable in ways that I don’t want. I want people to be active audience members, but I don’t want anyone to feel un-safe in my audience.

You’re very empathetic with the viewer. I like that, very thoughtful with your process. You’ve been bringing the shows to the bar, taking it to your peers, versus them coming to you. Is that something you’ll continue?

That is still my goal. We’ve been moving from bar to bar and now with Woodland Empire, we’re in a brewery and in our upcoming space at the Gem Center we still want to make sure we can bring in alcohol to keep it at that comfortable level.

How do venues feel once they’ve seen the production and your sold-out audiences?

They’d bring us in for a two-week run and we would bring in ninety people a night. Suddenly they’re like, “Oh, okay. Yeah, how long do you want?”

Is it strange to retro-fit a full performance into a restaurant/bar atmosphere?

Yeah, that’s a huge risk for them to take. The established relationships that we’ve built with Woodland and with [the former] Red Room were really invaluable, because walking into a bar saying, “We want to do theater in your space,” and they’re [thinking,] “Okay, you can do a one-night thing.” They always think it’s like sketch, something like—

Improv comedy?

Yeah. In our street clothes without production value. It’s like, well, no. We’re going to spend a lot of money on this. Just hold your breath, three days—once we get to opening night—you’ll see your venue in a way you’ve never seen it before.

But it’s difficult for you to get non-traditional venues on board with your vision?

Booking things has become too much of a burden—in the last year especially. We need a place where we can be trusted to produce good work. Luckily our patron base has followed us from space to space, but just finding them—finding the venues. Jaime and I are not event coordinators. That’s not our business.

When you’re a small company you really have to do it all?

Yes, and we need those venues to meet us halfway. We felt like the last few times we’ve scouted for a production, we could stage it here or there, but this play deserves so much better and the audience deserves a better experience. So, we’re going to shelve it; we’re going to put it on hold for a minute until we can find a way to meet our expectations. And that has been really difficult for us to continue producing, you know what I mean?

It’s a hard choice. But it’s admirable that you keep high standards for your work. How do you compare puppeteering to regular acting?

I don’t know, I swear to God, I feel like I am not acting when I’m puppeteering. There is something else. It’s coming through the puppet, I have so much more time and air and space to be listening to the audience, to be watching, and there’s a Jim Henson quote we love so dearly, I’m paraphrasing, that puppetry is the only performance art where you are both a performer and an audience member in the same moment. You’re reacting to what you’re seeing. A good puppeteer should be observing and watching every moment. It’s just a really bizarre thing.

Do you think a puppet is easier to project emotions onto rather than a live person?

Wall-E [the robot Disney Character] has got his binocular eyes and he’s immediately a person. We see ourselves in everything that he does. Especially when it’s an object on stage, I think people just want to go on that journey with the puppets, they want to see themselves in these inanimate objects. I think part of it for actors—and I am one—can be very self-conscious and when I’m a puppeteer it’s, “Pshew, I’m gone. I am free from judging myself.” I’m not in my head as much. I am that much more unleashed—to use the puppet to tell the story. It’s funny how many times people talk to me about [the show] as if I wasn’t in the piece! I say, “Well, I did this,” and they’re [surprised]—“You did that?” “Yeah, I was on stage for ten minutes holding that thing.” My face wasn’t hidden. They say “I didn’t see you. I just softened my eyes and watched the character.”

That’s awesome.

Yeah, that’s a very clear sign that we have done our job.

You want your audience to be fully immersed in the characters, and the story?

Yes, but it shouldn’t be purely a form of escapism. Show up and think. This is a form of art where we’re holding our audience members accountable, we require a certain fulfillment of imagination. Our shortcut to spectacle is puppetry, pantomime, and projections. And the audience is using their imagination to fill in the blanks. A passive audience isn’t an audience that’s learning anything. If you can sit back and enjoy your wine and enjoy your time, and I don’t know—

Completely check out?

Then, what’s the point?

You want to pose questions, not hand out answers?

Exactly.

Chad, you were telling me earlier about a one-act play in which you wrote Jamie in as your character’s girlfriend, when at the time she was dating someone else?

[It was written as] a very meta-experience where I woke up and I was a puppet one day and nobody would recognize that I had just—transformed. As the play continued, the threads of reality were bizarre and started revealing themselves and it became clear that my character’s experience of the world was not the experience that the other characters were having—because I was a puppet.

The other actors are playing themselves as regular humans?

And then there’s me puppeteering myself.

Got it.

[My character] got to work and I was working retail at the time and they said, “You need to bring this customer the red shirt that they asked for,” and I’d bring them the red shirt and they’d say “You silly, they asked for the red shirt and you brought a blue shirt.” I’m, like, “No, I brought a red shirt.” And the play would progress until work says, “You have to go home,” and on the way home, I go and meet—or my puppet [laughs] meets, Dr. Ian Malcolm, who is Jeff Goldblum’s character from Jurassic Park. He explains how chaos works, you know, he does the whole bit with the droplet of water, going down the lines of your hands: “You never know which way it can go. Some days you might wake up and find yourself to be a puppet. That’s how chaos works.” He tries the example but he’s got plush—fleece hands, so [the water droplet] just absorbs. [Malcolm] says, “You’re going to find the answers to your questions at the end,” and he leaves. My puppet says “What’s that supposed to mean?” And he goes to his butt and he finds a hand and he follows the hand up to me and I’m puppeteering him. He questions, “Why is my life this way? Why am I a puppet today? And why are you here?” “And who are you?” I say “Well, you know what? I wrote this play and I gave you my experiences, so you don’t remember not being a puppet because you have always been a puppet and you’ve got to go home because once you get home there’s the blackout and the end of the play and you have to meet it.” He goes home [to his girlfriend, Jamie] who was not my girlfriend at the time—not in real life.

CS: She was there and she has turned herself into a puppet.

JN: I say, “You were so upset about becoming a puppet that I turned myself into a puppet. Now we’re both puppets and we can be happy together.”

CS: But he’s, “No, that’s not how—that’s not how the world works. We’re not actually dating. You have a boyfriend. And he’s standing over there,” and he points at the audience and I wrote a line for Jaime’s ex-boyfriend, or current boyfriend at the time: “Hey.”

JN: He’d come every night just to say his one line, “Hey.”

CS: [He continues,] “That’s not how life works.” She says “Well, okay, but you have to meet your blackout.” And at the end of the play, you know, the lights would start to fade and he’d look at me and I’d tell him, “It’s okay,” and he’d be nervous and we’d give a little hug. And the audience in those weird moments is just like, “It’s okay.” And the hug would just—

JN: Slay them.

CS: You know what I mean?

I can almost feel it.

JN: And this was, like, the bar crowd, too, you know.

CS: And they would just watch. Watch as the lights slowly faded.

JN: But we were in the Red Room, so there was no ‘lights slowly faded’—there were clip lamps and the bartender would have to leave the bar, walk up to the stage, and untwist [each one.] He would slowly go by and [untwist] each of them, one at a time. And the whole audience going, “Don’t! Don’t turn off the lights!”

WOW.

JN: I know, I know, I know. It’s one of my favorite things.

And then the blackout.

Such smart work. I would love to see that. So many good life questions in there! Also I love the meta-story. How much time passed after that play did you become an actual couple in real life? [laughter]

JN: So that was “Puppet Affair”—

CS: “One.” It was the next year.

JN: Yes, the next year, working on “Puppet Affair Two,” I had broken up with that boyfriend.

CS: We’d always been very close—our working relationship.

Friends—working friends?

JN: He was my best friend.

CS: Yeah, my best friend. [Laughter]

JN: You were my first theater/stage kiss, and it didn’t even make it into the show.

CS: I had lots of theater kisses before you and me.

JN: Oh, I’m sure you did.

[laughter]

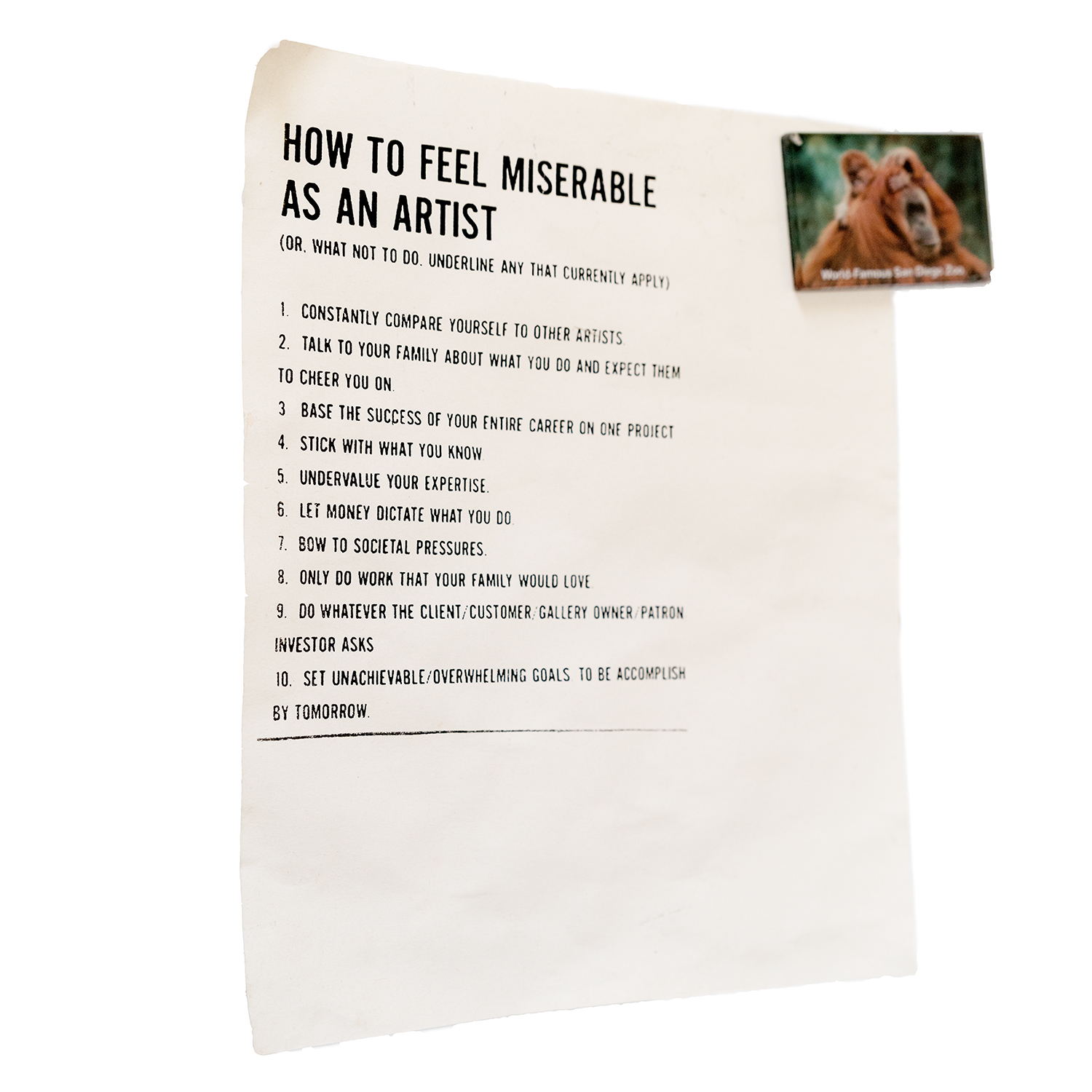

Would you say the theater community in Boise is competitive?

I don’t think so, but I believe that’s because I choose not to participate with a competitive mindset. There are not enough roles and you know, I think a lot of people feel like, from an artist’s standpoint, that you’re not always [busy working.]

There are only so many roles available?

As an artist, if you don’t always get the roles you want, it’s easy to slip into a competitive mindset. With different small companies, it’s easy to feel the same way, “Oh, so-and-so did this and now they’re getting great audiences or selling out and doing this and blah-blah-blah-blah.” That doesn’t help anyone; that kind of mindset is toxic. Who benefits from that?—nobody. We try really hard to support other small companies; on Facebook: “Go, see the show”— there’s so much theater happening in Boise! People probably have no clue. Chad and I are at the theater all the time. If we’re not making it, we are seeing it. I swear to God, we do nothing else. [Laughter]

Do you think there’s something out there for everyone?

This whole voice thing that I’m talking about—I really do want everyone in Boise to find the company or maybe even just the show that is right for them so that they can have at least one great theater experience.

A moment in which they are fully present, engaged with a narrative or a character that will stick with them?

JN/CS: Yeah.

CS: One of my favorite things about theater, why, in my opinion, it’s the best storytelling medium in the world that you can’t get anywhere else is, there’s a direct line of communication happening between the storytellers and the story receivers. And we’re in the same room and we’re all breathing the same air. And we all have to listen so closely to each other, and the second we stop listening to each other and we’re just focusing on [ourselves,] on why we’re so funny, pfft, you just killed it. And the communication has ended at that point. That’s the really hard thing to do, to listen. You know, I like to think that we are in the business empathy. And that our experiences, what we have learned, can help another person and vice versa.

So the true art happens between the storyteller and the audience, in that physical space and moment that cannot ever be exactly duplicated. And you do it all while being witty and refreshing, and smart as—heck.

Foothills East

December 20, 2017

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History.