Creators, Makers, & Doers: Kerry Moosman

Posted on 2/27/18 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton ©Boise City Department of Arts & History

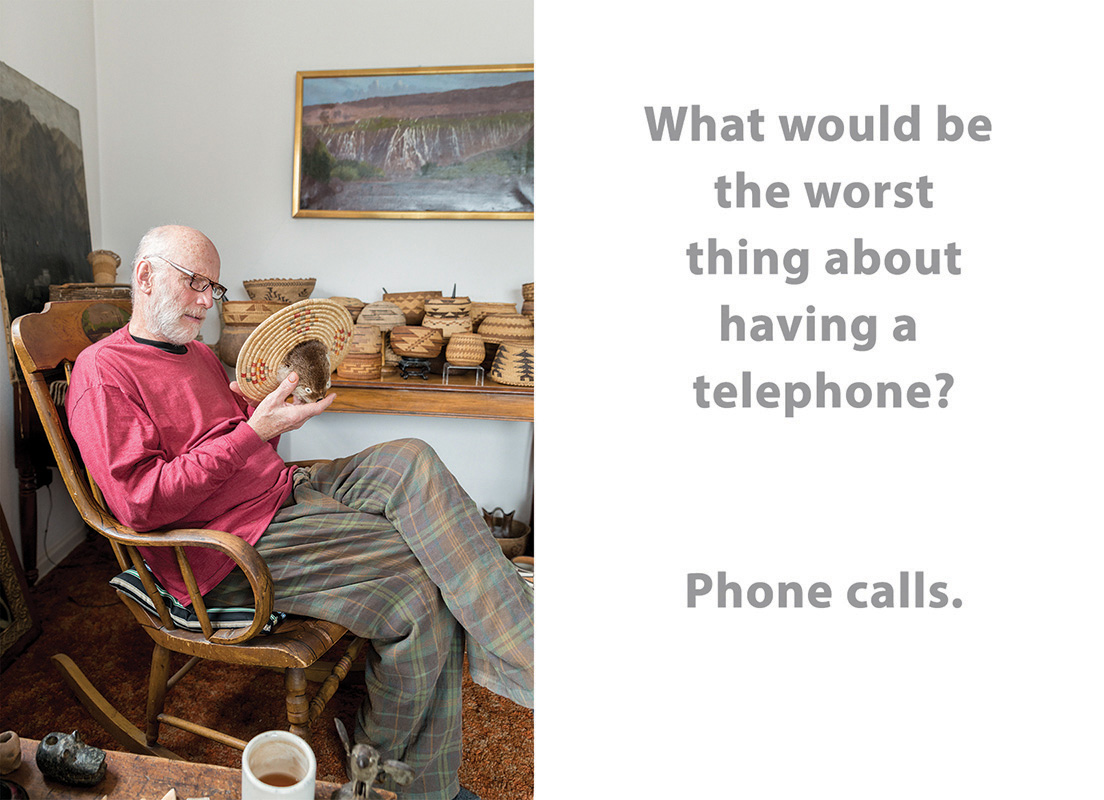

Kerry Moosman is one of the most recognized artists in Idaho, presented with a Governor’s award in the arts in 2006. His work has been widely collected and is regularly on display at the Boise Art Museum and at Boise City Hall. Working in clay, Kerry has described his vessels as sculptures of pots; the large forms are hand-built using a coil and burnishing technique that is labor intensive. Kerry was born in Idaho and lives in both Boise and Atlanta, Idaho where he is slowly documenting the town’s history piece by piece, and seeking out napping spots or watching the lightening roll in. Despite not owning a telephone, Kerry is easy to find; Monday evenings in winter & spring he teaches ceramic art at Fort Boise Community Center (with a break to watch Antiques Roadshow,) and in summer & fall he can be found at the end of the 30 mile dirt road east of Idaho City.

You’re a collector of many things but especially Native American baskets. I notice a lot of artists collect things, myself included. Why do we do that?

You’re a collector of many things but especially Native American baskets. I notice a lot of artists collect things, myself included. Why do we do that?

That is a good question, sometimes I think it’s the fear of emptiness. We don’t like a void, maybe. But when I look at this stuff that I live with, oftentimes I’m happy that I don’t have to make it.

[Laughs]

That somebody else already went to all the trouble of learning how and gathering the materials, preparing them, and doing it. It’s kind of a relief. It’s “Oh, whew. I’m certainly glad that I don’t have to do that.”

“I can look at this and enjoy it and love it, but I didn’t have to make it myself.”

Exactly, because people who aren’t involved in the art world don’t realize that there is so much physical labor involved. It’s a human activity that takes a lot of dedication and time and skill just to learn, and then to keep practicing.

And the specialty of developing your own unique vision that can’t be found anywhere else.

I think [collecting] is inspirational, if nothing else. You look at what other people did, what other people created, and it’s inspiring. For me it’s forms—it’s always a search for forms. It’s a search for simplicity. It’s good to create a volume in your brain of things that you like, and then create your own aesthetic.

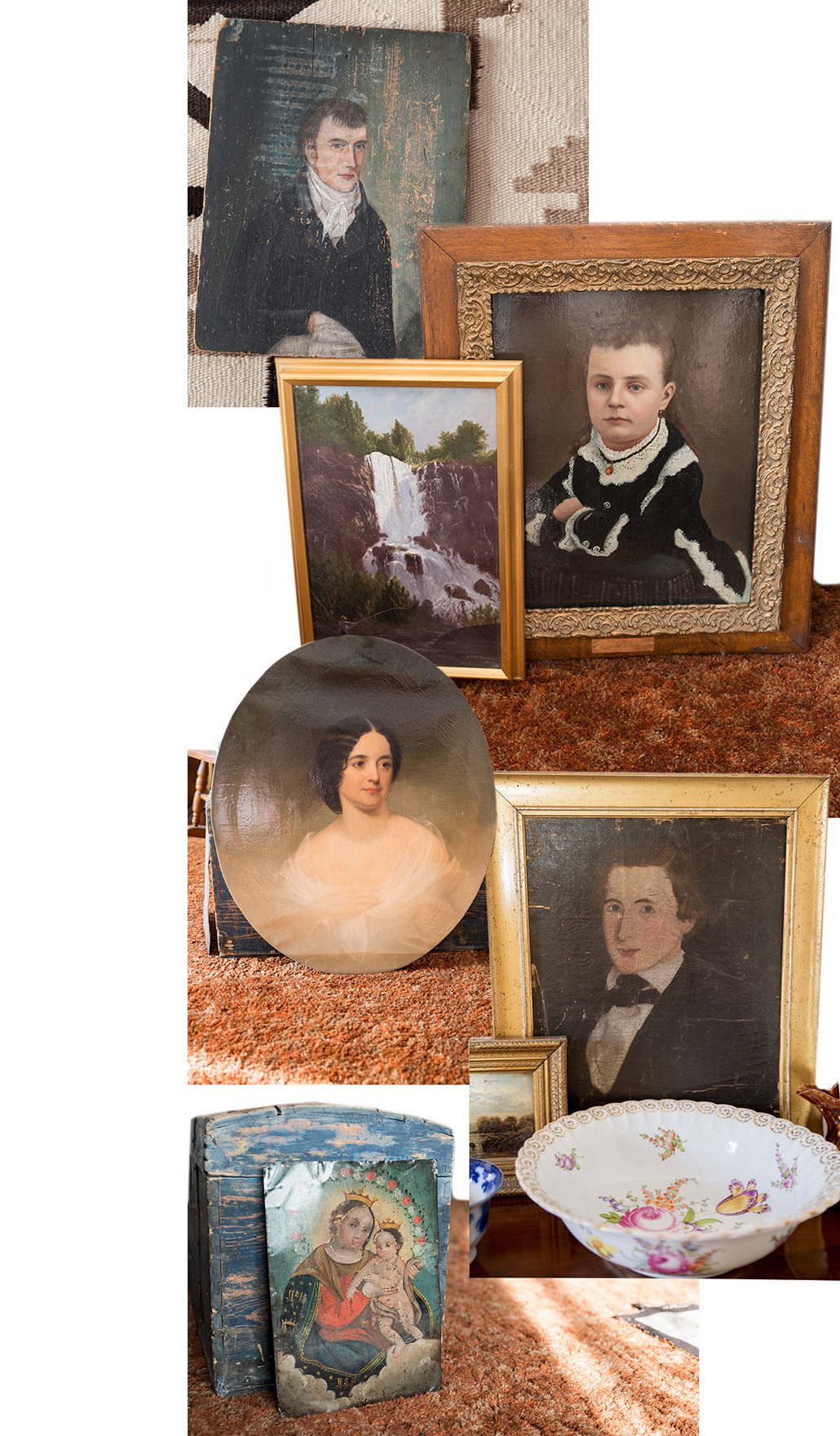

I think so, too. I think we figured it out. [Laughs] But yesterday you had a gallery dealer come out and hand-select items from your collection to consign?

Yes. It’s all swirling around in my brain right now. It’s just like, “Oh, my God.” I’m dealing with a loss today because so much is gone and it was a lot. We had to go through everything and analyze every object. [Laughs]

Did you hide anything away beforehand, something you couldn’t part with?

Not really, because I made up my mind, especially after that traumatic incident in Atlanta [Idaho] when [the Atlanta Club building] caved in last winter— I didn’t think that would ever happen; it was a total surprise. Of all the structures I have in Atlanta, it seemed to be the most durable, it was made out of concrete, it was newer than everything else, it was solid. But it failed. That’s just the nature of the material world. It fails periodically— no matter how permanent you think everything is, it’s all transitory. I have to look at all the objects that I was getting rid of [with the mindset that] somebody could break in and steal them, they could burn down, a squirrel could get in and eat all these baskets because they’re just made out of grass. It’s all just transitory, I have to keep that in mind.

Were you born in Atlanta?

I was born in Boise. I was born down here at St. Luke’s Hospital, so I’m working, like, what? Three blocks from where I was born. [Laughs] I went back to Atlanta when I was five days old.

They gave birth to you and then headed for the hills. What was something you got in trouble for a lot when you were a kid?

Peeing my pants. [Laugher] I really didn’t get into trouble much. We kids liked to snoop around in all the old buildings. There were a lot more then than there are now in Atlanta. It was more like a classic abandoned ghost town with old hotels and theaters and houses. We were strictly forbidden to go inside those buildings.

Oh, you were forbidden!

Because it was dangerous. There were wells in there, boards with nails sticking out of them. And, you know, dead animals.

Those are all the best parts. [Laughs]

Exactly, yeah. It was really hard to resist because when you’re a little kid you do a lot of snooping and exploring. We had our secret little hideaways—but we would get into trouble, if we got busted. But those old hotels were really interesting because they were so huge.

How many rooms?

Well the one on Main Street had three floors, a dining room and a kitchen.

How fun would that be!

I know, and staircases and, you know, all the old furniture that had gotten wet and—

Musty.

Musty, it was really, really, really fun. But they were afraid we would start a fire—

Did you?

We never started a fire, no. I did that—waited until later. I remember one place that was really interesting because part of the house had caved in, but in part of the house there was a perfectly made bed, you know, that had the sheets and the blankets and the pillows and we always just thought that was just the coolest thing to just have and see an old abandoned bed that looked like somebody was still using it.

Like somebody had just stepped away? What a wonderful way to spend summer days.

All that came to an abrupt end. When you’re a kid, you don’t realize that things are going to change, you know. My parents moved to Boise when I was nine going into the third grade. That was definitely an abrupt change from growing up in Atlanta. Then in the ‘60s, soon afterwards, most of those historic buildings were torn down in a short period of time. That motivated me to hang on tenaciously to whatever was left, but there wasn’t much left compared to when I was a child, so that has guided my activities up there. I guess it’s a way of holding onto a happy period of my life, when you were a child and carefree and people were taking care of you [laughs] and it was fun all the time.

Looking back, would you change any of that?

Not overly, because I have had such a charmed life. My life has been a lot different than most people’s. My time living in the mountains—I wouldn’t trade for anything. There’s definitely been some bumps in the road. The other half of my life is being able to work in an art studio. Between those two things, I feel very fortunate.

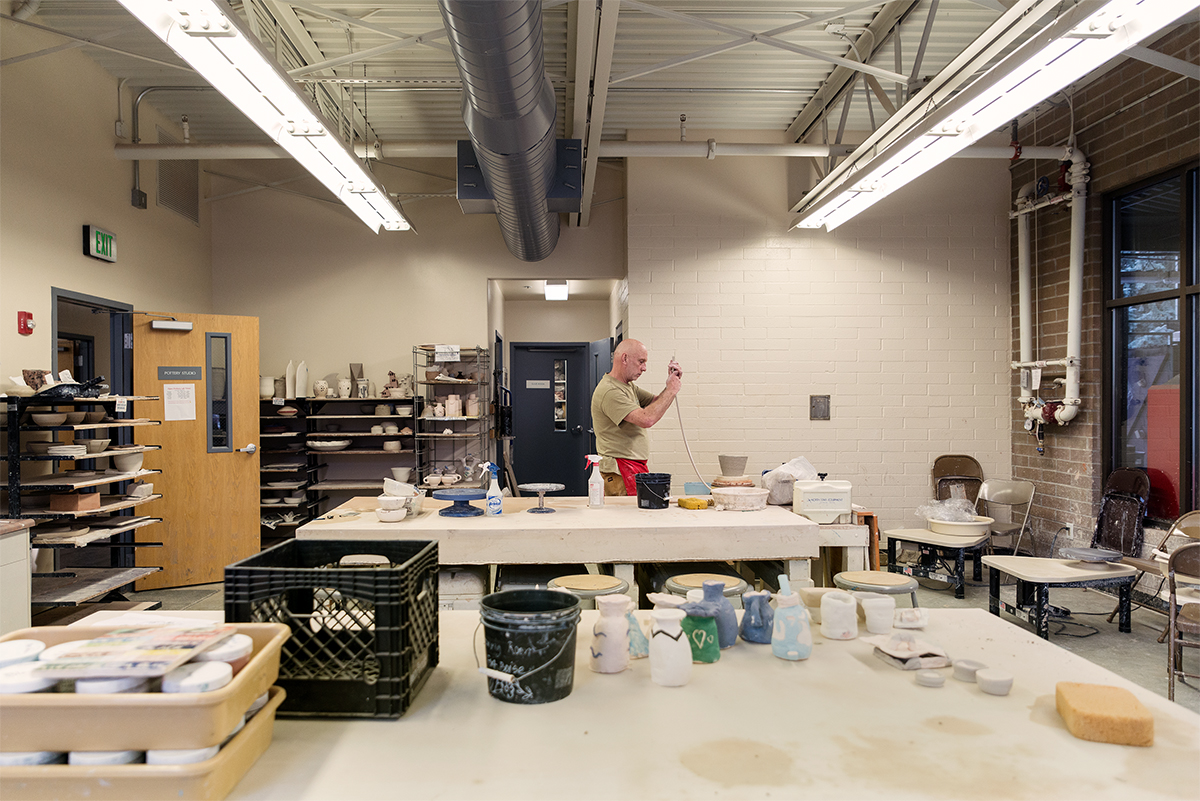

Tell me about working in the Art Center at Fort Boise Community Center.

It’s pretty quiet. It’s very ideal, because it’s a beautiful situation, a beautiful studio.

Sunlight coming in the window?

Natural lighting, everything you could possibly want, and it’s also quiet. This time of year—[winter] is a good time to leave the mountains and slip into the studio. It’s an easy transition and one I’ve done a lot. But that’s all going to change. I get used to that nice, serene, quiet studio time and then suddenly when classes start, it’s a lot of people, and a lot of activity and a lot of pottery being produced. It’s like a tsunami, a pottery tsunami.

When you’re working in the studio, are you ok with interruptions, or do you need to stay focused?

I do a lot better to stay focused. The way I work is really slow, repetitive and I usually work on one piece for a long time because I’m sort of a perfectionist. I’m very slow and it’s easier to stay focused if you’re not around other people, you know, people coming in and changing the radio station or talking about their hemorrhoid operations and all of that sort of stuff. [Laughs] I have less and less time to myself down there.

You know what I bet? If you had all the time in the world to just work in solitude, I bet you would get bored.

You know—you need a certain amount of that.

You do. You need a certain amount of interruptions or distractions because it contributes to a sense of urgency in wanting to accomplish a goal.

But, it’s a beautiful situation down there, it’s very interesting to see the variety of work, the kids’ stuff and, the special needs people, they all have their own approach and it’s just endless, the variety. And the way clay moves and the way it fires and, to be around all that movement and activity is inspiring.

Do you have any pet peeves?

Pet peeves? Well, of course, yes. There, at the studio, it’s sort of contagious; one person will do a certain thing then everybody is doing it. Like, neti pots, suddenly, everybody’s making neti pots [laughs] and it’s just, like, “Oh, Christ, if I see one more neti pot, I am just going to—I don’t know what I’m going to do.” It’s sort of funny in a way. I mean, I try to cultivate a sense of humor, maybe I shouldn’t make fun of people’s—

Neti pots?

I have to kind of chuckle a little bit about all that stuff.

When you get into the creative zone, where does your head go?

I stay really focused on what’s happening with the medium.

So, it’s very sensory?

Yeah, one of the things that I do is the burnishing and you have to really concentrate on that because if you don’t you’re going to screw it up. People ask, “What do you think about when you’re polishing?” It’s like, “I’m thinking about doing a good job of polishing.” I’m not thinking about what I’m going to have for lunch or how I’m going to pay my bills or any of that stuff. I am totally focused on doing the best possible job I can with burnishing.

That sounds very rewarding and relaxing.

Burnishing is good if you really want to slow things down.

What are some other ways to slow down time?

Well, the way I do the coil building, people always say, “Why don’t you use an extruder?” This machine—you put a big chunk of clay in there and you—splat—push down a handle. But I like rolling coils. I don’t get tired of it, it slows down time. Just a simple, repetitive activity. I’ve been crocheting lately and ripping up fabric and making rugs. I do that in the summer. There’s plenty of old fabric around—old clothes. It’s sort of rewarding—using scissors and cutting something up, because most of the rest of the time I’m taking pieces and building something. Most people look at me and they think, “Oh, God, that looks so boring. How could you do that for all these years?” But—I never get tired of doing it. And somebody asked me the other day, [laughs] “Are you still having fun?” It caught me off guard, it’s like, “Oh—well—yeah. Otherwise I wouldn’t be doing it.” I mean, because it’s not for the money.

Right. Making art is not as much for the money.

There was a time when maybe, but—

Well, you mentioned that people stopped buying ceramics around 2008?

Kind of in there. It definitely slowed down to a trickle. The trickle turned into [laughs]—

A drip?

A drip. I always thought it would get a little easier somehow. I thought the art world would get a little easier as you got older.

Does it not? [Laughs]

It didn’t. No.

Oh, shoot.

Because, maybe it’s just my personal situation, but I had some success when I was young, as far as selling. And having an audience. All the [commercial] buildings that were being constructed in Boise at a certain time were building art collections and the corporations were building art collections and people personally were buying art, and I know I keep harping on this but I just don’t know what happened.

The recession?

I guess. All those galleries [closing]—and it’s not just Boise, you know. It’s an across-the-board thing that’s just changed. I have an article on the bulletin board that I just put up about the galleries in New York that have all closed over the summer. The only market that has shown any growth is the million-dollar-plus purchases.

That’s really high end [laughs].

Yeah. Everything else is declined.

Why is that I wonder?

Well, it just becomes a trophy-hunting. Because people who spend twenty or thirty, forty million on a piece suddenly they are sort of famous, along with the piece, because they’ve paid that much for it. It’s a way to be recognized.

Buying art for the wrong reasons?

Seems like it, yeah.

Does anybody ever call you up and say, “Hey, Kerry, we broke the piece we purchased from you?”

Yes.

What do you do then?

I hang up on them.

[Laughs] Okay. Good to know.

I’m not a conservator. I mean, there are people who do that for a living and they do a beautiful job.

What would be an awful career for you? What would you be terrible at?

Oh [laughs], pretty much everything. Anything that has to do with sports, [laughter] because I’m not interested at all. Also, I don’t like—it’s funny because I collect a lot of paper stuff, but I really hate bureaucracy. I really hate filling out forms. And I really hate pushing paper. But, as a historian, I rely on a lot of paper.

[Laughs]

All you have to learn about early history is what people wrote and the paperwork that they kept. But I don’t really like producing it myself, filling out forms.

What kinds of things keep you up at night?

When people steal things from me. I’ve had that happen in the past because I’m gone from Atlanta five months out of the year. It’s like, “Where is it? Why did they do that?” And also, when I can’t find things. I have collected a lot of historic Atlanta material—the photos, the journals, the letters; I try to be organized and file things, but when I can’t find, like, a collection of photos or a particular photo in a collection, that keeps me up at night.

I hate it when I’ve purposefully stashed away something special, but I can not remember where. I’ve basically hidden it from myself.

Yes. Also, I meet people, maybe, whose great-grandmother lived in Atlanta and, “Oh, I’ve got her photos, I’ve got the letters her father wrote in 1870.” I have a list of all those people, so sometimes I start going over it, thinking, “Oh, I forgot to contact them.” “Oh, I wonder if they’re still alive.” “Oh, I never did get around to sharing information with them.” So, that keeps me up, too. There’s a lot of things that keep me up.

You say you forgot to contact them. But you don’t have a telephone.

No, I’ve never had a phone.

So you contact them—?

Usually, I just write letters. You know, I use the mail.

What would be the worst thing about having a telephone?

Phone calls. Getting phone calls. [Laughter]

Is it the obligation that would come with it?

Well, lack of privacy, probably. Just always being available.

I get that. Just the ring can give me anxiety sometimes. Earlier you mentioned a house fire in Atlanta?

That was in 1976 after I had graduated from college, I was tired of going to school and I was tired of living in the city and I really wanted to just take some time to breathe, figure out the next step. My friends and I moved to Atlanta and we were doing it the old way, you know; we canned peaches and Scott got a deer and we had this beautiful old house that I restored, and we were all set up for the winter. We had art supplies and food and firewood and, yeah—that place caught on fire and burnt totally to the ground. Everything was gone. There is nothing that survived the fire.

In the middle of winter?

It was in February. February is not a good month for me because that was the year of the fire and it was also the year of the cave-in [in Atlanta last year.] You know, you deal with one of those disasters in your life, you think, “Well, that’s probably it. It’s probably not going to happen again.” [knocks on wood.]

You thought you were in the clear?

I was wrong. It’s funny, or ironic; that one disaster was with fire and this [recent] disaster was with ice.

So, you still have a disaster with air and earth on the way? Look out for tornadoes and mudslides.

[Laughs] I know. I do have a little post-traumatic stress—I find myself afraid to move sometimes, I’m just sort of frozen. For every action there is a reaction, you get a little scared, what is the reaction going to be, you know?—I need to get back to the point where I’m having more fun. This has been so grueling; rebuilding [the Atlanta Club] for five months.

That is a long time.

Grinding and ripping and tearing and it’s like doing surgery and putting things back together.

Also you’ve got workers calling: “What do you want us to do with this? What do you want us to do with that?”

Exactly. It was a lot of physical labor and a lot of trauma. I had that building for twenty years. All the major [work] was done, all the hard stuff—it’ll take me probably another twenty years to get back to that point and I’ll be eighty-six years old [laughs], so then it’s like, “What the hell?” [Laughs]

I can see why you’re having some trouble moving in any direction.

Yeah.

Are you much of a planner? Do you look forward towards the future?

I always have. I work off of lists.

Did you make a 2018 list?

A lot of it is this restoration of the club in Atlanta. There are certain things to make it comfortable, to make it livable. A chimney would be nice. The floors are all popped up in the dance floor, so get the floors redone so we can have nice dances up there. Because it was nice having a dance hall in the town.

Do you have any trouble with following through on your lists?

Yes. Those are the resolutions that keep me up at night—doing more history stuff. I’ve collected all these historical [artifacts] and interesting stories—historic photos. It’s like, “Okay, now what? What are you going to do with all his stuff? Just turn it over to somebody else and let them have all the glory of doing a book or putting together a collection of stories—are you going to let somebody else do all that while you’ve done all the work?”

Well, that is kind of a huge, lifetime goal.

I’m protective of that, too, you know.

I understand protective, for sure.

You go to all that trouble and all that time finding the information, maybe a little bit of a hoarding instinct or something and it’s [become] so personal.

Yes, and if someone steals a photo, you are wondering “What did they do with it? Did they throw it out this window on the way home? Or do they treasure it the way I did?”

They don’t. They didn’t treasure it. I know. It was just being mean.

How many buildings up there are under your family’s name?

Oh, gosh. We have the Atlanta Club, the service station, the Main Spread, the barn, the assay office, the Heidi Bowl, the Cindy Bowl, the Barber Shop, the Company House. So—sort of like ten.

How many of those do you sleep in?

Well, I take naps in different places because I’m sort of like an old lizard—I just sort of go find the one that’s the perfect temperature. Certain times of the year some of them warm up a little more than others. And then when it’s hot out, some of them stay cool. So, I just go around and find the one that’s the perfect temperature for napping.

Mountain naps are the best.

But, generally, I have one bedroom that I sleep in at night, but napping can be most anywhere.

All those buildings are unique, is there one you identify with more than the others?

The one I’ve stayed in the most was the old Main Spread, I was there for, like, forty years. I look at it as the mother of all shacks. That’s the one I started working on in 1976 after the other one burned down. There was quite a bit of room so all my friends started coming up and staying, too. It was a lively place, it was a lot of fun. But, I sort of ended up being the maid and I got tired of that. Everybody would leave on Monday and come back on a Thursday, so Tuesday and Wednesday was—

Cleaning?

Oh, cleaning, changing beds and all that sort of— it was fun but I got a little grouchy about it. When the guests start inviting guests, that’s when you know that you better do something a little different. If you’re having so much fun here, you probably need to buy your own place. I’ve done that with everybody, kicked them out of the nest.

You said in another interview that living in a town as small as Atlanta, you don’t get to choose your friends?

[Laughs] Well, that is true, you know. I think that is a worthwhile—a way of living. Certainly, I grew up that way.

Like a village?

Exactly, a village, in a place like that, you get to be friends with old people and alcoholics and—there’s kind of one of everything up there. Down here it’s a lot easier to get stratified into a certain strata.

You choose who’s in your circle and if you’re like me, you tend to choose people that are similar to yourself.

Yeah, and that’s not always good [laughs].

No.

I don’t think so.

It’s diversity by proximity and isolation. But there is a growing community of creatives types up there, with the Atlanta School?

Yes, and I enjoy the artistic community. After you hang around with people who are involved in the arts and who are focused on creativity, everybody else seems sort of boring.

I’m embarrassed to admit that I know exactly what you mean.

It’s just like, “Really? That’s what you do for a living?—“Well, that’s so nice that you make so much money, but you’re kind of a bore.” I don’t say that, but I really enjoy my friends who are always searching and who are creators.

Do you still have family in Atlanta?

Most of them are dead. I’m getting close to being part of the elderly part of the community, which is sort of a strange transition—and I miss that group. My grandparents and parents, that [generation]—they’re all pretty much gone.

I don’t like those transitions.

Yeah, so suddenly, to be in those shoes, it’s a little strange.

You think it will never happen to you. [Laughs]

No, you don’t. And it goes by so fast. Gosh, I look at my friends. It just seemed—it was yesterday that we were just—

Bouncing babies on your knee?

Bouncing them. And now they’re looking at colleges and going away, and it’s like, “Oh, my God.” That was a fast sixteen years. That’s all it takes and then they’re gone. I don’t like that.

Life is weird.

It’s sort of cruel in many ways. I guess that’s part of preparing you for dying, you get a little more aware of how mean [life] can be and how cruel it can be. But when you’re young, it’s just always fun, fun, fun. And then just one at a time, there’s setbacks— you lose people and you lose your eyesight, and all of that. I’m struggling with eyes and endurance.

There are also different responsibilities when you move up a generation.

Well, and the legacy, too. What are you going to leave behind? What is worth passing on? What knowledge or association? Your family instills certain values as you’re growing up and you absorb them. Some of them you don’t want to pass on.

I’m highly aware of that.

[Laughs] And some of them you do.

Is there a certain value that you’ve shared with people in your life?

A lot of it is my association with the mountains, Atlanta, and a simple lifestyle.

Simple living is making a comeback.

Yes, a lifestyle that is not just dependent on an urban setting. There are other ways of living that can be very rewarding. I’ve always had my nieces and nephews around and they’ve sort of bonded with the place. I think in some shape or form they will probably keep that association.

What if you had to choose between Boise and Atlanta?

I live in Atlanta five months and I live down here for seven months, if I had to give up one and make a choice, I would live up there full-time.

Why?

It’s more fulfilling. I breathe differently up there. Everything is so big up there, the mountains and the rivers and the wind and the space—all your small problems seem trivial. I like that your struggles just sort of melt away because they’re not really that important in the big scheme of things.

That’s some perspective.

And it’s just hard to be in a bad mood when you’re surrounded by natural beauty; you go outside and look at the mountains—the lightning and storms moving in. And the feel of the air is totally different. The coolness, the temperatures in the morning—all of that, I’m so addicted.

You crave it?

I just crave it and I’m always satisfied that it’s still there.

I hate my life. Well, I mean, you know.

Central Bench

February 28, 2018

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History.

COMMENTS

Marilyn Brown says:

You are a precious gem. I am so grateful l have the privilege to be in your class.