Creators, Makers, & Doers: LED

Posted on 6/25/18 by Brooke Burton

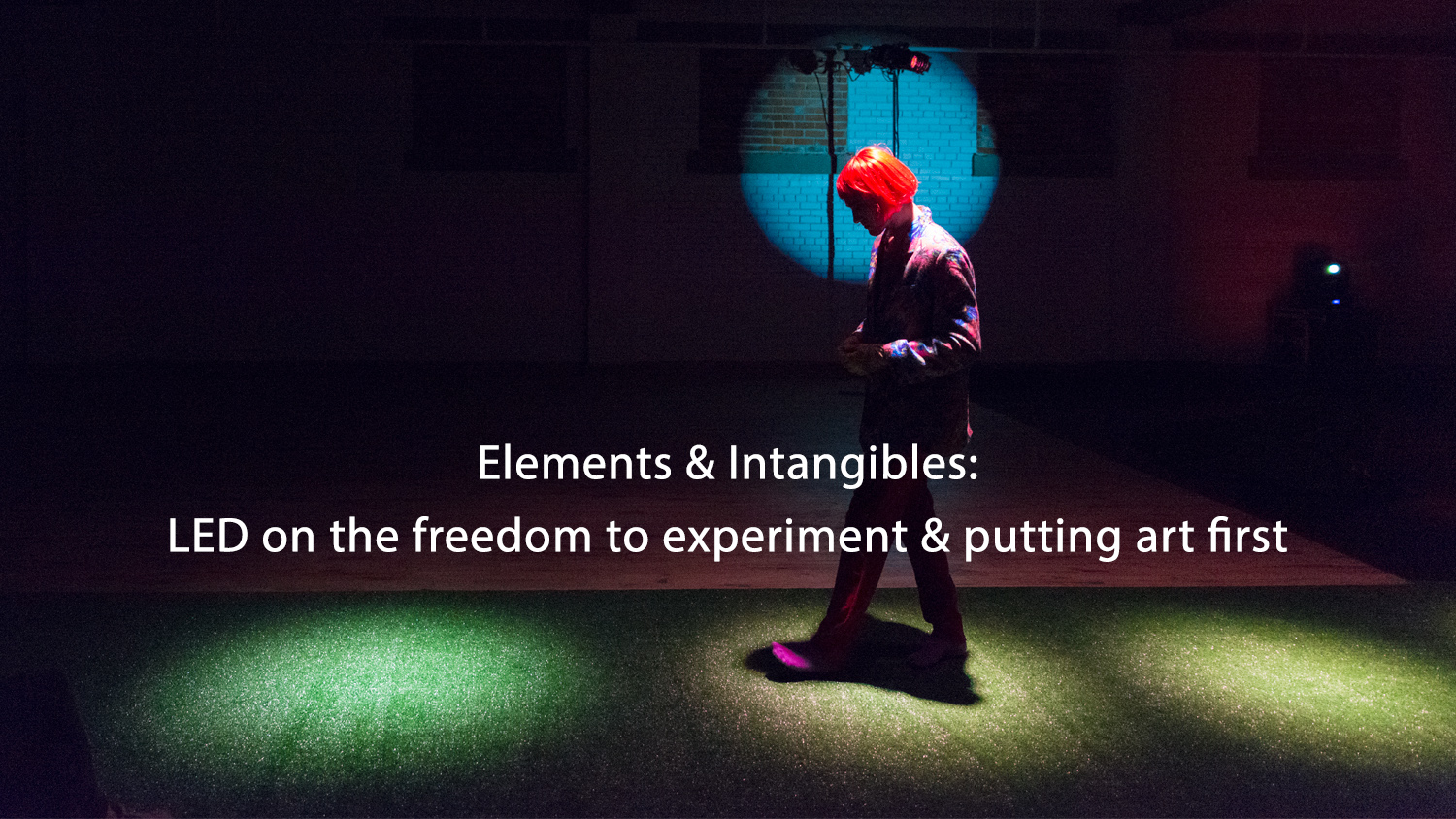

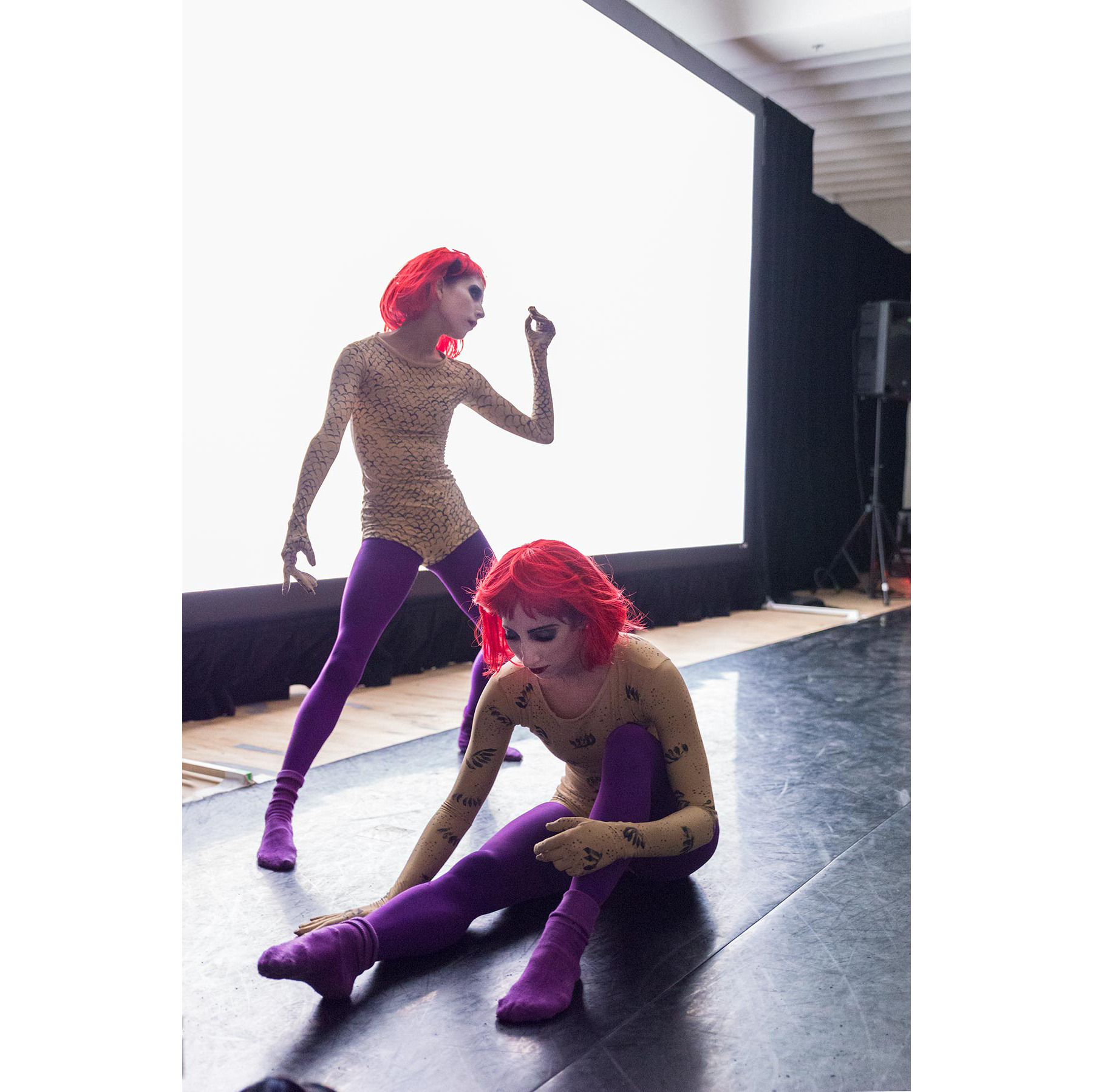

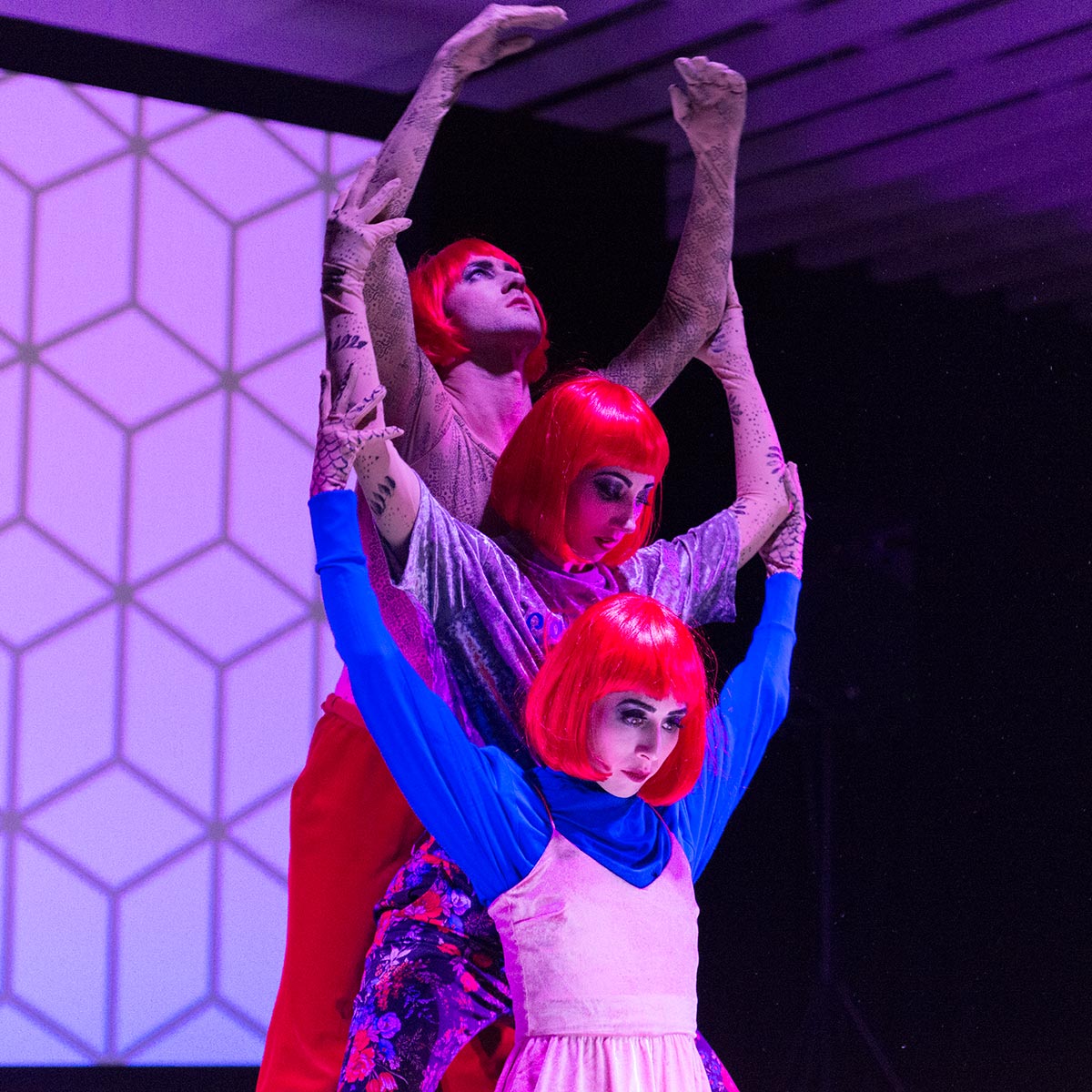

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton ©Boise City Department of Arts & History

LED performances are high energy sensory experiences that draw you in with original dance, music, and visuals created by a trifecta of talent: Artistic Director/ choreographer/ dancer Lauren Edson, Creative Director/ composer/ musician Andrew Stensaas, and Managing Director/ filmmaker Kyle Morck. We photographed a rehearsal downtown in a BODO warehouse for Artificial Flowers, a conceptual piece performed at Treefort Music Festival: a synthesis of color, texture, story, and dramatic movement both playful and dark at times with raw emotional peaks. Artificial Flowers can be seen again in September at the Egyptian Theatre along with new work, old favorites, and a few surprises mixed in. Back at their newly established studio on Broadway Avenue, we chatted about LED’s purposeful shift in creative process, the rarity of female choreographers, and the difficulties of running a nonprofit in a time when the donor class seems to be a thing of the past. LED is about satiating that gnawing urge to create and chasing artistic highs, multiplied by three.

I was checking out your website profiles; you guys are funny! [Laughter] It’s clear that you aren’t taking yourselves too seriously and I appreciate that. Is humor important in your performances?

It’s a big part of how we work. You don’t want to take yourself too seriously because then you’re [over] focusing on details that can tailspin into Nowheresville. We need a little bit of witty banter and fun to get our brains prepped for long stints of sixteen-, seventeen-hour days sometimes, to meet a deadline.

Laughter as a source of energy, but also an art making tool?

Yeah, hopefully that humor shows in our work. I think laughter is one of the most genuine reactions an audience can have. You laugh when something surprising is happening, or unexpected. It’s something we value because it means you’re really connecting with the audience. And we like to have fun.

But I’m sure it’s not fun all of the time?

There’s a sanctity working in the studio with dancers, the ritual of creation, but I want to allow for moments of levity to happen. We are trying to get to that humanness in each of us. We want to laugh, we want to cry, we want to feel moved. Recently, we’re working to open that window even more, just making sure the audience knows it’s okay to laugh. So often, with art, you’re not getting those cues, so you feel self-conscious [as an audience.] That was one thing interesting about Artificial Flowers—how each audience reacted differently, to see what a certain group found funny and where it snowballed into more laughter, but also where a different group felt more self-aware or, weren’t ready to go there.

There’s a fine line: laugh with me, laugh at me, or don’t laugh at all.

We’re exposing parts of ourselves, as artists, we’re putting our personalities out there. In some situations you can feel like the art is compartmentalized from the people who create it, but just by nature, there’s an extension of us in our work, always.

AS: You guys really dove into the more intellectual aspects of why we’ve got to laugh. [Laughter]

It’s easy for me to jump in and talk about the ritual of creation and artists as compartmentalized from the work, but we should probably cover the basics: What is LED?

Yeah, I mean—We’re working on it.That’s one thing that we are really trying to come to terms with. How do we put into words what LED is?

Words are hard.

We can talk about the components, the ingredients: movement, original music, visuals, and film. Yet, it’s greater than that.

Greater than the sum of its parts?

It’s what’s produced from those elements that’s intangible and hard to describe.

Great art usually has an intangible element.

What it comes down to in a practical sense is that the three of us work here full-time and we come up with an idea that is artistically motivating and exciting. Then we bring in a lot of talented dancers and musicians and visual artists and designers and put on a show or make a movie or do something else entirely different. People often think of us as a dance company—

Thank you for putting that out there. I was wondering, “Should I ask them if they’re a dance company because nowhere does it say ‘We are a dance company’?”

We don’t want that association—that’s not what we want.

You don’t want to be limited by that title?

Right.

You are a musician, a filmmaker, and a dancer who makes things?

Yes, there we go. We each bring our individual expertise: Lauren is an amazing choreographer, Andrew is an amazing musician. Kyle’s an amazing filmmaker. [Laughter] That’s not the only way we think of the collaboration, because we’re all putting artistry into it. We could very easily do something that doesn’t involve dance at all, but Lauren would still be just as involved, we’re coming in to create together, but what we create could be anything.

Generally, it’s culminating in a performance or film—something for a viewer or an audience to experience?

Yes, and the physical experience of the audience is a big piece there.

What are you excited about right now?

Well—[pause]

Everyone just took a huge breath! Why!?

We’re going to—can we get into this, can we talk about this? [Laughter] It’s going to happen, so, yeah. We’re working towards the development of a weekly video. Interesting Failures is kind of the title, IFs, as of now, anyway.

Have I heard this concept before?

It comes from Mark Duplas, the director of Room 104, the HBO series. They make twelve shows a season and he wants to allow, maybe eight that are pretty good and well received by viewers, then four that are interesting failures, giving himself the freedom to do the kinds of things that gnaw at him as a creative person. I think that is inherently a huge part of what we want to do. We want to stay true to what is interesting to us. That’s been the hardest thing because we’re essentially in our third year of existence as a nonprofit.

You’re babies! And Interesting Failures may not pay the bills?

Exactly. We have been growing the foundation, but we’re quickly getting to a place where our interests aren’t just about doing a show at the Morrison Center every year. We love doing that, but that’s not all we want to do. It’s hard to give yourself time to make other things. It takes so much work to put on a full scale show, we could easily spend all of our energy just working on that. Interesting Failures is a challenge to ourselves: we’re going to try to make something new every week and put it online.

Are you unified in how you work?

Creating bodies of work together have led us to understand each other on a cognitive level. In the beginning, you know, it was all about fresh ideas and just putting them all out on the table [at once.] Now in the two years we’ve been together, there’s a maturity in the way we work: we can produce exactly what we’re going for instead of experimenting with an idea and saying, “Let’s just hope we get to the place we envisioned.” Interesting Failures is dabbling back in that challenging territory that is less predetermined.

Are you talking about staying in the moment and improvising?

Yes, and also taking away the stakes. If it doesn’t work out, then we’ll do something else next week.

As opposed to when you’re talking about becoming established and producing a scripted performance that have a beginning, a middle, an end, and a ticket value, right?

Right. For our next Morrison Center show, we’re going to start working eight months before—and that’s a pretty short amount of time, really, to make a full-length work, but that’s still eight months where we’re artistically focused [on outcome.] IFs is giving ourselves the ability to experiment, even while we’re putting on those bigger shows.

Will it exercise your creativity in a new way?

Yes, it’s a little less analytical and restricted to a different time frame.

Interesting things can happen with a short turnaround time, can’t they? Happy accidents?

I think there are different things that are ignited in you when you have a deadline, like Andrew says, he likes to work with a gun to his head. [laughs] But I think there is something [that happens] when you have to follow that first impulse, when you don’t have time to let it marinate, but there are different ways of working for different situations. We want to mix that up, to find different modes of working and not edit ourselves and get to a place where we’re working from the subconscious. Rather than trying to shape our vulnerability: just be vulnerable. There are so many facets to the creative process, and we’re open to exploring those.

Vulnerability is trending right now, thanks to Brene’ Brown’s Ted Talk. Also, your experimentation, your practice with Interesting Failures is going to feed into the bread-and-butter Morrison Center performances in the future.

Vulnerability is trending right now, thanks to Brene’ Brown’s Ted Talk. Also, your experimentation, your practice with Interesting Failures is going to feed into the bread-and-butter Morrison Center performances in the future.

Or even bigger things.

And it will continue to grow your unique personal vision. What a perfect idea!

Exactly. You get it.

I love it when people say that. We need to go back to introductions: all three of you attended Boise High School at one point. Were you there at the same time?

AS: No. Kyle is younger than both of us.

LE: And Andrew is two years older than me. But he knew my older sister. Our story is incredibly convoluted and I don’t even know [laughs], I don’t know if we can cover all of it.

Now I’m more curious, and so I have to hear this convoluted story. Sorry, Kyle, this is going to be about these two—

KM: That’s okay. They’re married. They’ve got more history.

LE: I graduated from an arts high school, then spent a year at Juilliard, then was at Hubbard Street in Chicago, then made my way to Portland. Andrew was in Portland, journeying on his music.

AS: Questing.

LE: I went to the venue where he worked pretty often, but again, we never crossed paths there.

AS: Which was probably the best thing at the time.

LE: I ended up moving to Boise to dance with Trey McIntyre Project. Andrew came back to Boise as well.

Andrew, you had a band in Portland?

AS: Yeah, we had had some minor success, you know, we made some MTV videos and thought we were going to be rock stars and all this. We were self-managing and some members didn’t do their part and it kind of all fell apart.

Is self managing something you would recommend?

AS: I would do it again, but it’s not for everyone. But in your early twenties, making decisions that are more like: living the lifestyle before you get there, you know, fake it till you make it, doesn’t necessarily work in rock and roll. [Laughter] Because you have to gain a level of maturity—

And skills?

AS: Yes, in the other aspects of the business. So, when that fell apart, you know, I came back to Boise and then—

LE: And then we [laughs], we met at my Grandma’s funeral.

AS: And the clouds parted. There was actually a tornado that was projected for that day, and we saw each other and the heavens opened.

LE: We went on one date and we’ve been together ever since.

The best stories are true stories! Lauren, how long were you with Trey McIntyre Project?

LE: Three years, but I had this need and push to continue choreographing, and I felt it was being overshadowed by my desire to fulfill someone else’s work. I loved being in the company; to be able to return to Boise where I grew up and studied was awesome. I never imagined a company of that caliber would be here.

How do you two start collaborating?

LE: I had gone out on my own professionally, I was commissioned by a festival in New York to create an original work. I loved Andrew’s music and said, “We should work together on this. I’d love for you to create all the music for this piece.” It was an incredible collaborative experience, which I’d never had before.

Awe!

AS: We realized we could work closely, not only in the capacity of what I do and what she does, but conceptualizing and designing together.

And you have a son together?

AS: Yes. We basically took a year off—we had a lot of time to talk and think.

LE: It’s funny because—when I was pregnant, I mean, my world was pretty much like this big (pantomimes holding a dime.) My [planned] trajectory did not include having a child in the immediate future.

That is a huge life change.

LE: Yeah, it was nuts. For me, at the time—I didn’t want to have anything to do with dance anymore. I felt like part of me had to die.

You’re making me so sad.

LE: But six months after Finn was born, we said definitively, “We want to start this company.” We had been talking about it before, but there was a panic about having an infant and trying to start a non-profit at the same time. Ultimately, after we had a few months with Finn—

And the shock of parenthood faded a bit?

LE: It was, like, yeah, I mean, why would we not do it?

AS: Babies don’t end your world.

I get what you’re saying, though. You had a mini-death of, self, I suppose, and then a rebirth when you realized your creative life didn’t have to die. But when the baby’s not sleeping through the night and you’re not sleeping through the night, you kind of want to die. [laugher]

LE: Yeah. I mean—I couldn’t see past my stomach [laughs]. I felt so physically incredibly different and I was thinking of myself differently.

Could you imagine if you had given up? What would you be doing right now?

LE: I don’t know. I imagine that we both would be creating in our own capacities—probably on separate paths. But [perfect] timing has been everything for us—

AS: It really has.

LE: Doing that first project together was all I needed to know that I enjoy the creative process more when I’m working with [Andrew,] I enjoy it so much that I want to put everything into it.

How did Kyle enter the picture?

LE: I had been a fan of Kyle’s work, but not knowing who he was. My admiration came to a head when I saw a projection that he had done for Trey McIntyre and I finally put his name to his work . There were so many things I was drawn to, I think we have a similar aesthetic, wanting to create work that has the impact and volume of cinema. Kyle is an expert in a lot of those things, and to have a third voice is an essential ingredient. I really believe that so much of our strength is having three of us—we all work very differently and we push each other a lot, but end up with a product we’re all really proud of because of that.

Who suggested the trifecta?

KM: Throughout that early process, Andrew and Lauren were trying to figure out what the company was, organizationally. That is something I’d had an interest in while working at Trey McIntyre Project. I paid attention to those things and had some ideas about how to run a nonprofit. So, I was like, “Why don’t we just start working together full-time?”

You are a good group, very dynamic. When I look at your work, I see a lot of narratives and characters emerging.

We’ve delved a lot into human nature. We do love character and we love all the aspects that come with cinema. When you’re watching a film, there’s something visceral and all-consuming that draws every bit of you in, as opposed to trying to watch something that’s more obscure. We really like the accessibility of empathy when there’s a person on stage, a person that you can make a connection with. It’s easier than trying to make a connection with an idea as a construct or something like that.

So the strength of having a character is something for the audience to latch on to?

Yes, as an entry point. It’s always surprising, though, just the nature of art. I mean, we set out—sometimes pretty explicitly—the expectations of a work. But it is often interpreted in vastly different ways, which is beautiful. It’s important for us to feel deeply connected to it, and for me narrative provides that. Story-telling is such a beautiful human thing that’s been happening forever, and to tell a story with movement is exciting because it’s not the standard.

Rather than telling a story with words?

Right. How do I get across the essence of my idea through music or projection? How can we really fill these spaces and provide different entry points to meaning, whether it’s abstracted or not.

We’ve got to talk about costumes too, because your performance is very visual. The costumes are high impact and highly stylized. But from a dance history perspective, costuming is about showing the body, highlighting technique and form. It looks like you’ve taken those expectations and tossed them?

We come at it with a narrative perspective and wanting to believe that these are real people, that they’re not dancers. I mean, they are dancers but that’s not first and foremost on my mind, it’s not the point. I want to feel something more. Costumes are indicators saying, “This is what I want you to focus on.” With “Artificial Flowers,” it was important that the dancers appeared alike, exactly the same, with an element of androgyny. And then they shed the top layer of costume to reveal another layer. That seems to be a recurring theme: the act of shedding some element and a pedestrian aesthetic.

When you say pedestrian in terms of costuming, it means—

Clothes that aren’t made for dancing in. Yeah, they’re not Lycra. [Laughs] You aren’t wearing booty shorts. I think a lot of choreographers are going that direction too. We have established that dancers have nice bodies, you know, and that we want to see them move, but now we want more than that.

Is there a transition happening in dance at large? It’s a big, giant question, sorry. I’m wondering if a lot of choreographers are moving past technique and body and looking for more?

LE: I think so, and there’s a wave of so much more. Like questions about who’s choreographing, a man or a woman? There aren’t a ton of female choreographers in the arena and who are called upon the way male choreographers are, that’s just the truth. There are conversations being had now, which is a step in the right direction.

Why do you think there are fewer women choreographers?

LE: Just the ratio of men to women—there are, I don’t know what the statistic is, but there are so many girls in class versus one boy. As a female, you’re fighting for the ability to dance and be cast, to be at the top. The number of girls vying for one position is huge. So, you’re not working on your craft as a choreographer. You’re not in the back observing what’s happening around you and thinking, what would I do differently there? What do I want to explore as a creative person?

You already mentioned you have a strong drive to fulfill your own vision?

LE: I’m very happy with the things that I’m doing and the fact that I’m an artistic director of an arts organization, because there really aren’t many of us. There needs to be more. We also need opportunities that aren’t compartmentalized for women choreographers, because, when you say, “We’re doing a program; we’ve commissioned three women, but they will only exist on this one program for women,” we already marginalize their abilities and don’t allow them to be in that same arena as men.

No one likes to be marginalized.

LE: It’s awesome that these things are being looked at; it’s important to realize that each of us individually are part of the building blocks to make change.

Nice—high-fives are happening. [Laughter] That was a lot, Lauren, well said. As you were describing it, I’m thinking, it sounds like your personal journey; from dancer to artistic director.

KM: That’s something truly special about what Lauren’s done, she created the opportunity for herself.

I am so proud of you right now. Making a living as it can’t be easy, either.

The core of what we are trying to do is the idea that artists should get paid for what they do and that their main focus should be on creating art. We’re not trying to build up programs that are getting their own funding, then spending all of our time—

Doing the side projects?

Yes, thinking about the side things, then try to squeeze the art in last. Our whole model is based on keeping it as sustainable as possible, so the art is always at the forefront.

How do you keep it sustainable?

We talk about Ed Catmull’s book, Creativity Inc., which is about Pixar, because something he talks about is not feeding the beast. That is very much the cycle of an arts nonprofit: You want to create something; to do it, you need to get funding; but to get funding, you have to promise to do new things, and then to do those new things, you need to bring on more staff. When you bring on more staff, then you have to get more funding, but to get that funding, you have to promise doing new things.

I can see how it spins out of control. You aim to keep that loop tight?

Yeah, it’s lean. We don’t try to chase money. Just because there’s a grant we could get, if it’s not something we’re already excited to do, then we won’t apply for it. Our income streams are very traditional for a performing arts nonprofit, because, as every nonprofit knows, the donor class it dying out and it’s not being replaced. We’re able to reach younger audiences, but younger audiences aren’t going to replace those donations, so I feel the focus is [misplaced] on trying to right a sinking ship. Instead, we are trying to keep our ship small so we can do whatever makes sense at that point in time.

More like a speed boat? Or three jet skis?

Yeah, our big goal is trying to find unique alternative funding models.

Well, you’ve got a brain trust going here, that’s for sure. I can’t wait for your performance in September, we’re lucky to have you here.

And we love Boise. We’re not just developing a show that is scale enough to tour. It’s something we’re putting on in our own town to share with the community. It feels good.

What does success look like for you?

Our goal isn’t to have ten full-time dancers; our goal isn’t to be doing forty-city tours every year. The big thing that interests us is making cool things for people here in Boise, because we’ve lived here the vast majority of our lives. We could have easily decided to start a company somewhere else; but we want to make something cool here in Boise.

Downtown

June 27, 2018

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History.