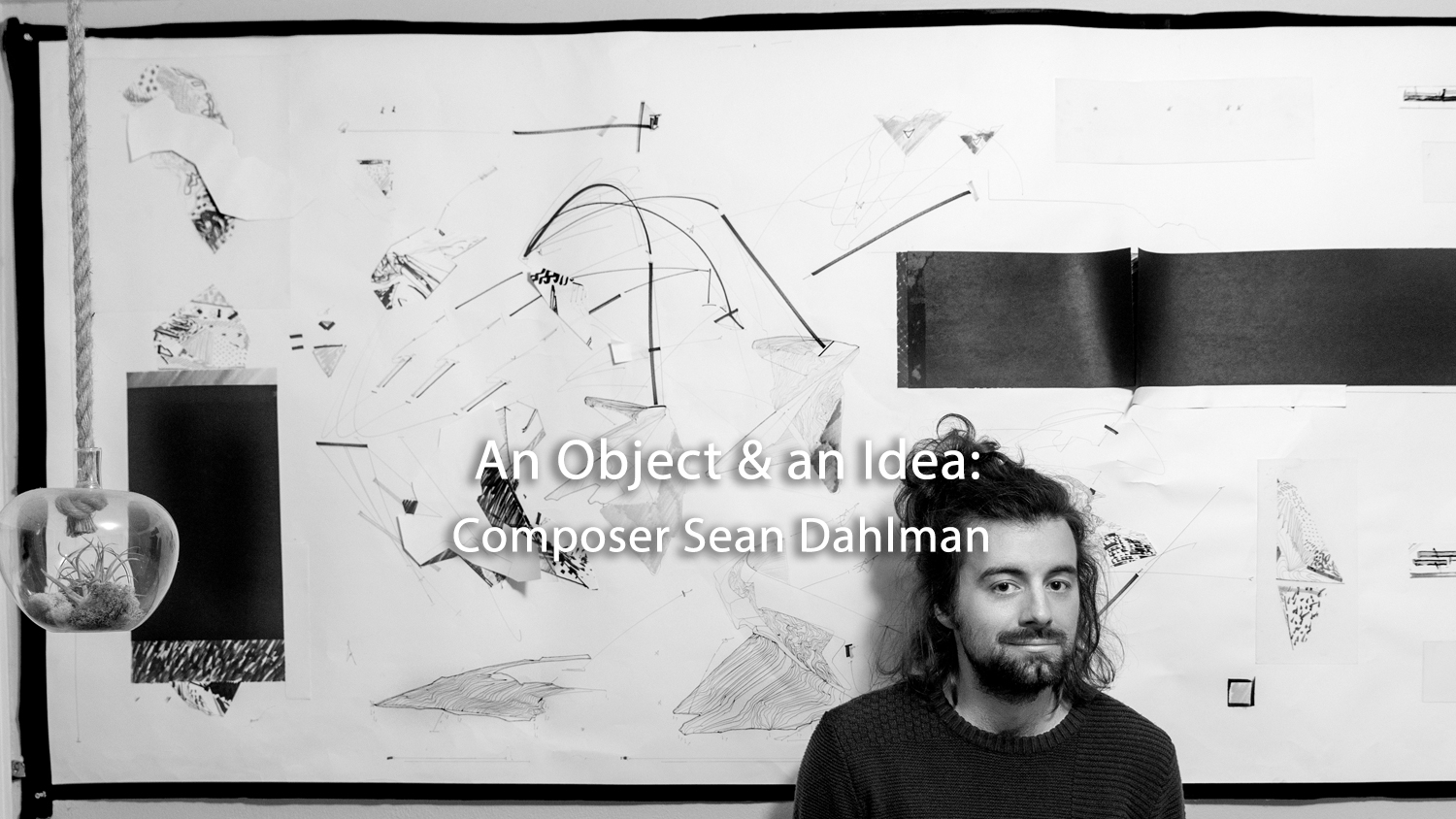

Creators, Makers, & Doers: Sean Dahlman

Posted on 4/3/19 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton ©Boise City Department of Arts & History

Sean Dahlman earned his degrees in both music and conservation biology from College of Idaho. He is a composer and musician, recently inspired to expand his artistic practice. Moving from musical performance and orchestration into the visual arts, he is exploring a dialogue between sound and sight through experimental video. A recent collaboration with painter Garth Classen involved an object, an idea, and destruction. The results are abstract, ultra slow motion visuals set to original compositions using synthesizers and stringed instruments. This is the beginning of a creative journey, a path Sean purposefully avoids defining or directing in order to allow projects to manifest on their own, in order to embrace the brilliance of unpredictable situations, and to let go of tangible meaning.

How did you get into photography, which then led to the video work?

I was working in an undisclosed GMO research facility somewhere in Idaho, I was a research technician. It was the most soul-crushing job I’ve ever had in my life. Met a lot of cool people, but the work itself was devoid of meaningful human development. I truly felt like my job should be automated to spare future humans of this work.

[Laughs] You make it sound so horrible.

It was—I worked alone, which, it’s probably the only job I’ve ever had where I wished I wasn’t alone. [Laughter] For two weeks, all I did, I would count to a hundred, put those hundred objects onto a scale, and then write that number down.

Over and over again? It does sound horrible.

Oh, yeah, and the thing is, “You need a science degree to work here.”

Which you have.

Yeah, at first I was pretty excited. Then, naturally, my body, as if it were crippled by starvation, had to survive, and I did everything I could to maintain myself. I started to notice certain patterns [in the objects] and started to take photos—just to keep myself occupied, to keep my mind sane.

It was a little creative outlet. I mean, in the smallest sense of the word “outlet.”

It was. I viewed it more so as when a Bedouin sees an oasis. I’d just see endless sand and I needed to drink.

Something, anything.

Anything. So, I would take photos. And then someone noticed.

They saw you taking pictures of the objects in the lab, with your iPhone?

Someone walked by and noticed. They started to build a case against me. In secret. One day, I was pulled into the office and there was a lawyer there, the regional manager, and head of security was on this little telecom thing. They had a projector going, they looked at me and said “We’re on to you. What have you been doing? You’ve been taking photos and you’ve been in contact with our competitors.” They created this conspiracy that I may have been taking photos for the Land O’Lakes butter company.

Because you’re a butter spy?

Butter spy? [Laughter] And because they also deal with GMOs. I’m like, “The butter company?” And then I immediately left that place.

Well, you were asked to leave.

I was not fired. I was told to not come back. [Laughter] There’s a difference. Legally, there is a difference.

“Asked not to come back.” [laughter]

I was discharged with a new fervor for visual art and I had developed a gag reflex to corn.

You’re funny. What is your day job now?

At the Forest Service, I help run a federal nursery-slash-farm, it’s a small crew, and together we grow roughly four to five million trees and shrubs a year.

Is that up past Lucky Peak? You drive up there every day?

Every day.

What do you do on the commute?

I sit in silence. [Laughter]

Forty minutes?

Yeah, forty minutes.

In complete silence.

Total silence.

You have a bachelor’s degree in music. Somehow I thought you would say you listen to music while you drive. Or maybe a podcast. Do you have favorite musical artists?

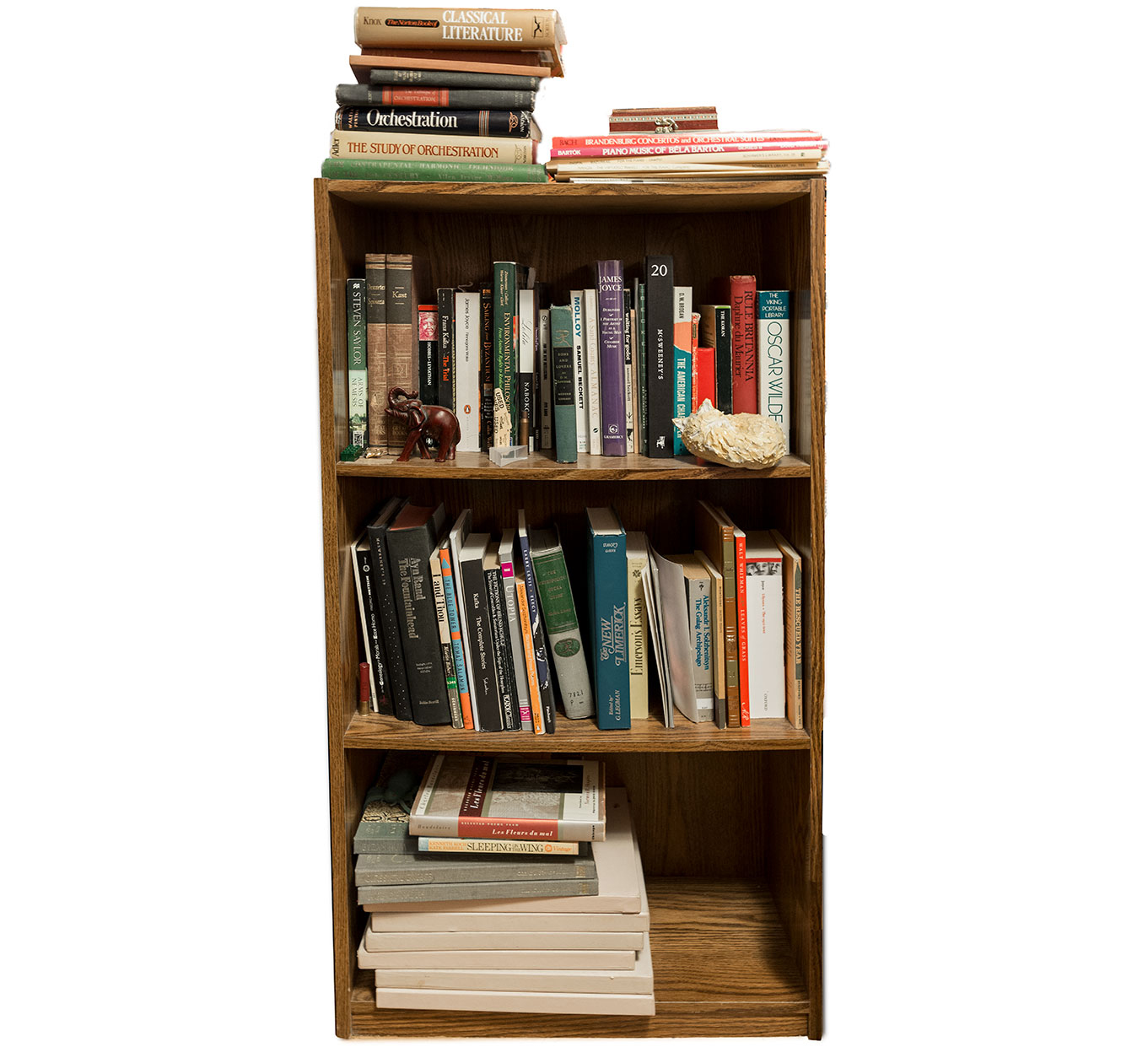

I do. I have favorite composers. It’s hard for music to be a passive thing for me. When I’m driving, music can actually hinder my ability to drive safely because I’m analyzing it while I listen. A gloss goes over my eyes. My favorite composers range from any particular thing I might be studying at the moment, but usually Maurice Ravel. He has probably had the most influence on me. Handel—I love Handel. Beethoven once said he would throw his body over the grave of Handel and after studying Handel’s music I see why. I mean, I do occasionally listen to music on the road, a handful of songs that I repeat. Ravel’s “String Quartet,” a choral piece by Handel, maybe something by Ligeti or Schnittke.

What kind of music do you compose?

I guess the closest thing to it would probably be post-Impressionism. I love how melodies—the linear way ideas can be constructed through Impressionism. Impressionistic painting outlived the artists who created it. But Impressionistic music practically lived and died with the composers.

I’m getting a music history lesson here.

Impressionistic music was never really emulated after the death of these composers. It was not as emulated like the other genres, like Romanticism or Expressionism or Atonalism.

Would you say you’re emulating or expanding upon?

Well, I’ll let other people tell me if I’m expanding. I am doing my best to emulate.

What instruments are you interested in?

I have my favorite instruments to compose to and my favorite ensembles, but, when a melody or an idea surfaces, usually a natural form of orchestration will follow.

The melody comes first, then?

Not always [laughs]. Sometimes money comes first. It’s just one of those things, it happens when it happens. I never think about it and I never really force it.

That must be nice [laughter]. I’m forcing things all the time.

I push myself to completion, but whatever falls within my lap is what I run with.

Which instruments do you work with?

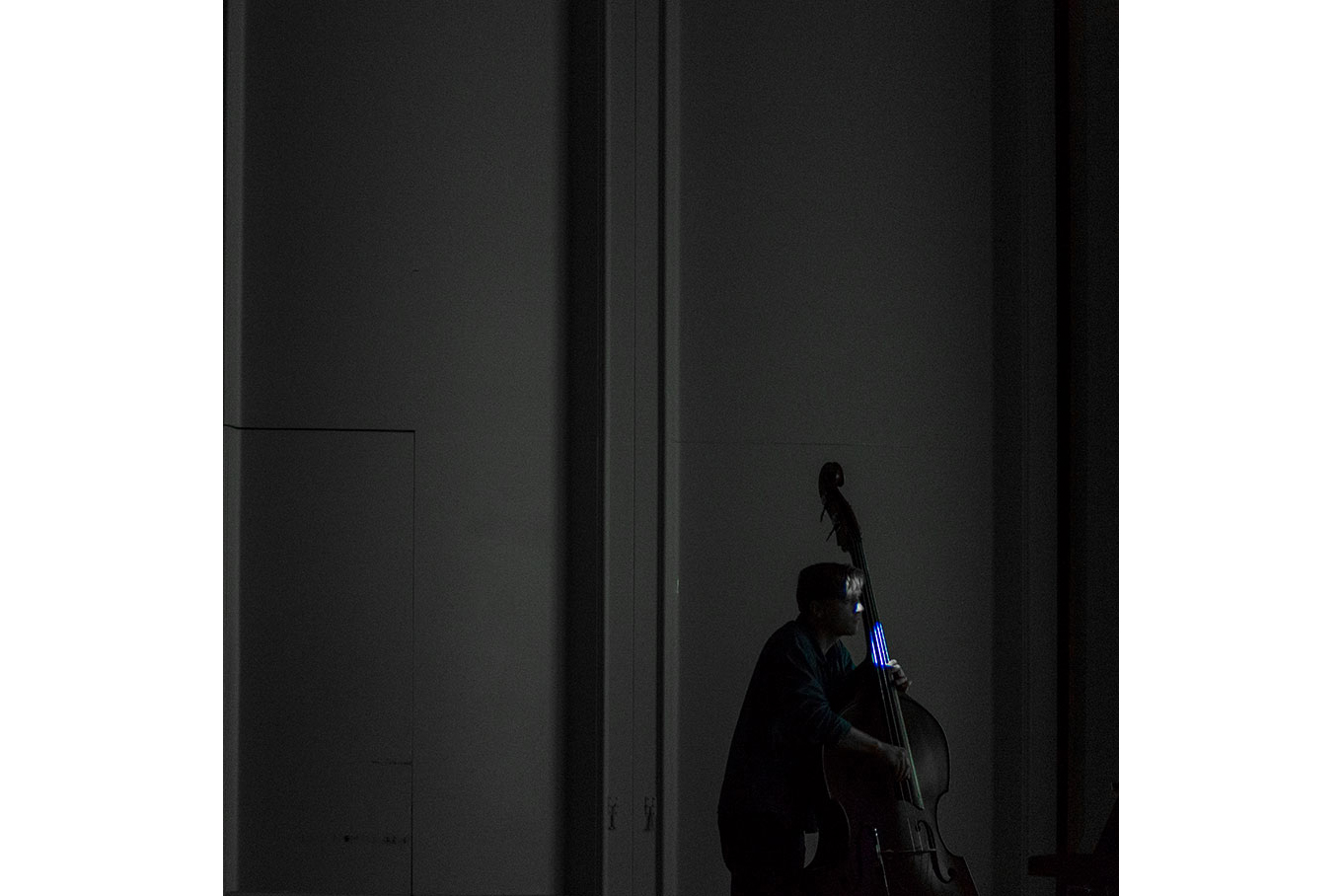

Usually it’s an amalgamation of piano plus, whatever. I really love doing chamber compositions that have a piano element with strings, voices. Even though I may think of myself as a composer, there’s still a part of me that is very much a performer, and my rock-and-roll background does not allow me to relinquish the stage. I want to be a part of my own composition.

You prefer to be on the stage?

Oh, totally. I always write music in a way that I can somehow be part of it physically.

Do you have least-favorite instruments, like “the oboe—ugh, so horrible”?

Oh, the oboe is one of the most beautiful, most delicate instruments [laughs]. I love the oboe, but the English horn could be proof of the weakness of man. [laughter] Not every invention is a good idea.

That is hilarious.

To be fair, the English horn is great and all, but I feel I can achieve the role of an English horn with different [instruments.] I just don’t like the timbre, I don’t like the embouchure.

You just don’t like it.

No orchestrator should not like or dislike an instrument. Maybe one day the English horn will invite me, but that has not happened yet.

[Laughs] You are the youngest composer I’ve ever met, or even envisioned.

The youngest?

I think my preconceived notion is that a composer is someone with gray hair or a white beard. How many other people did you graduate with that are composers?

Very few, if not one.

Exactly.

There are professional musicians and brilliant songwriters, but a very small handful of people still actively pursue orchestration. Very few.

I lied. You aren’t the youngest composer I’ve ever met. You are the only one I’ve ever met.

We hide in our apartments.

Tell me about the band.

Zach and I—Zach is one of my closest and best friends; he and I started music roughly at the same time, independently, and discovered each other in high school. To this day, we still play music together in a band called St. Terrible, it’s a multimedia freak-folk band. We try to do a fully immersive experience through sound and dance. We just wrapped up Treefort.

What is your artistic process like?

My work is becoming more visual and avant-garde, but I still maintain my passion for chamber orchestrations. My process is relatively the same; slowly working through musical motifs and letting go of tangible meanings.

Tell me about the installation work.

“Gradient.”

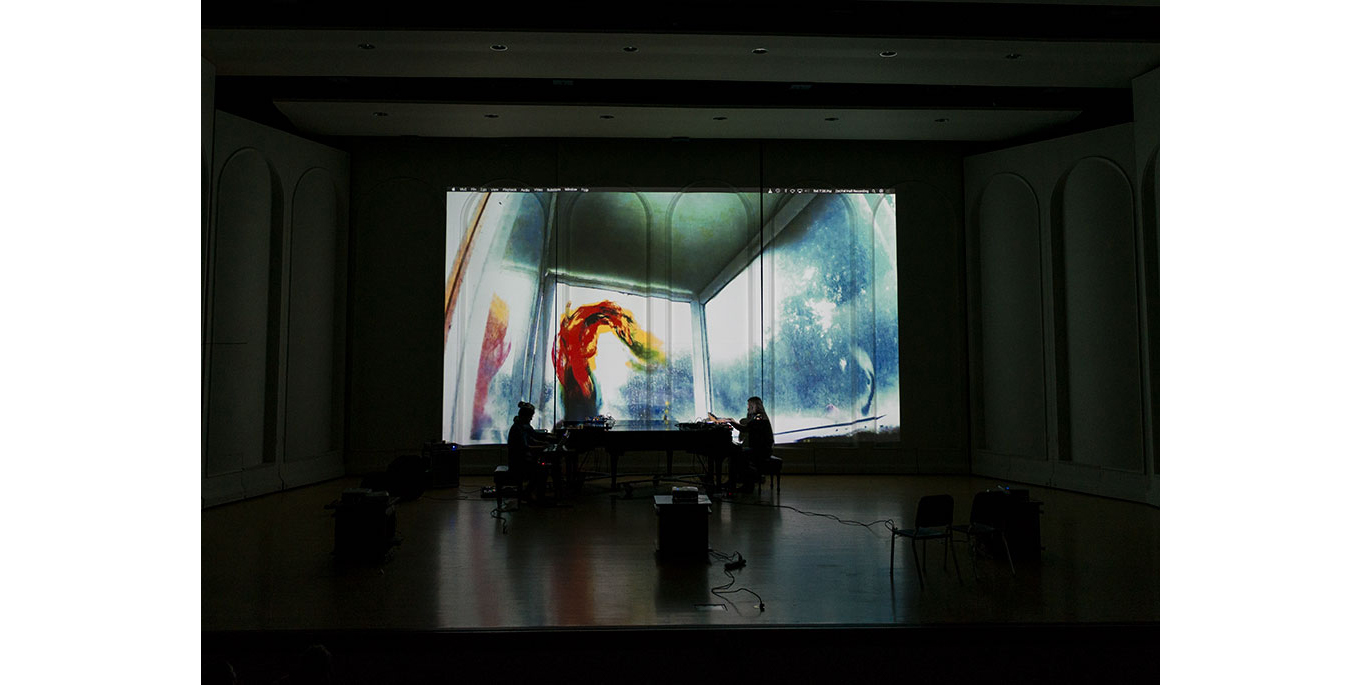

Yes, “Gradient,” if I’d walked into MING Studios on the night of that performance, what would I have seen?

You would have seen a dark room with bearded men. [Laughter] A dark room and projectors being shone on the walls. We had one, two, three, four, five projectors going.

That’s a lot of projectors, one for every wall at least.

There were a lot of things artistically that could stand alone, that we put together; it was very visual-heavy.

Sensory.

We had the dance performance, and the videos, which I made and to complement the dancers. We had music going.

Why that title?

“Gradient,” we felt was a good name because, it begins with one color, ends with another color, and it’s a blend. The work is like a gradient of abstract visuals that slowly lead into a human presence. And during that time in between, the humans—the dancers—are interacting with the videos and it ends with the dancers alone, eventually leaving the stage.

I was able to see a version of this performance and the videos on campus at College of Idaho. Some of them involved non-objective sculptures by artist Garth Claassen, but they were destroyed?

I’ve been working on slow-motion videos for the past two years and I wanted to take it to the next level, I would have an idea and then we would take it out into the woods and then—

Wait, you’d take an object out into the woods?

An object with an idea.

An object and an idea.

We would take it out to the woods and my friend Ashton would shoot at it with a shotgun and I would have a GoPro or my iPhone. This was before I owned a camera. I would put my iPhone in the crossfire and I’d tell Ashton, “Just don’t hit my iPhone. It’s all I have”— that’s how it started.

You were driven to go out and shoot things for a creative purpose?

How it all started, I was in downtown Denver with my dear friend Steven Anderson who’s a brilliant freelance writer. We walked into a gallery and there was a room with a bunch of chairs and a video. The video was a camera inside a house, and the house was rocking back and forth on the water. Afterwards, I kept on thinking about it, kept on thinking about it, and later that night, I looked at Steven, “That artist was on to something. It needed explosions. It needed color. And it needed really good music.” So, my original idea was to build a house and to throw it out of an airplane. I found a pilot. And then I found out that I probably shouldn’t do that—

[Laughs]

I couldn’t afford special effects, so “Let’s just shoot at it.” I’m not really into guns, but—

Well, the word “destruction” came up.

Yeah, destruction. From there, it slowly came a point where I needed to take this destruction art and evolve it. Garth Claassen is an artist that I’ve worked with before. I would play music and he would paint and then I would take those paintings and turn it into a small string ensemble with singers. He’s a great person to collaborate with, down for anything. He’s a brilliant sculptor, his art resembles sculptures.

His two dimensional works have an emphasis on planes that reference sculpture.

Planes, exactly. Architectural planes, so, “Okay, Garth, would you be down for doing this?” he was “Sure.” [Laughter] A few months passed, he didn’t hear from me, then I showed up in his studio, literally with armfuls of trash, stuff we bought at the Second Chance construction place. “Garth, here it is. Could you make something about of this?” He’s, “What are you guys going to do?” “Oh, we’re going to blow it up and film it with a camera.” “Oh, is that legal?” “Don’t worry about it, Garth.” [Laughs]

Don’t ask; don’t tell.

“Just trust me.” [Laughs] During this time I was doing rough drafts and I finally saved enough money to buy that Sony camera. I would like the Forest Service to know how much time I put in to get this camera. Garth’s pieces were ready, we were ready. The camera can shoot at nine hundred frames per second for only two seconds. So we had two seconds. We did a lot of planning, took his pieces out into the desert, I mean, out onto private property where it’s legal—and we lit them on fire—not during fire season—and then proceeded to shoot at them with guns. Ashton and Seth were instrumental in the destruction of that, as well as Blond Tony.

Blond Tony?

He’s an associate. [Laughs]

You added color and sound to the visual element that originally inspired you, the video of the rocking, floating house. Do you remember the name of that artist?

Not at all.

That’s too bad.

Actually, I’m okay with that.

It’s too bad for me. Your visual work, it’s partly—the aesthetic and mood. And it’s about the action—does it matter what you’re blowing up? Does it need to be a sculptural artwork? Can you blow up anything?

Oh, I can blow up anything. Anything [laughs]—but, the next step, I felt, was, “let’s get some professionally made artwork, with a nice background and a professional camera—then blow it up, see what happens.” Because I don’t know what’s going to happen, I have hopes, I have an idea, that’s it.

It’s very abstract work and very engaging because these semi-recognizable objects—a two-by-four, a metal pole—are twisting and contorting very slowly. Sometimes they start on fire or there’s a spray of sparks. The ultra slow motion lends a living quality to the sculptures as they are being blown to smithereens. I think it’s because during that process, the material bends and bows in an organic way that we normally associate with the movement of a body. My question, what is the next step?

Well, we’ll see. I’m working on a new project series that will probably be releasing in the next couple of months.

What is it?

[long pause]

You’re not going to say! How about a hint?

A hint, well—

[another long pause]

Do you want me to re-frame the question?

Sure. [Laughs]

Are you working on a project that is video-based?

Oh, many.

Okay. No. Is the new work video based?

Yes.

Does it involve people or objects?

People this time.

I’m so excited! That’s what I was hoping for.

Yes.

You’re not blowing them up?

No, no, no. [Laughs]

I’m wondering if we can go back a bit. Why do you think you weren’t ready to share about your next project? Are you feeling protective?

It’s not so much that I am protective. It’s not like I am worried about any kind of intellectual theft. It’s just, by keeping my ideas cerebral, I am not bound by any type of expectation.

I like that.

Because sometimes when you talk about something aloud, you then solidify certain aspects.

How did you learn that?

I’ve had a lot of moments through college and post-college where certain projects could not be completed, or were, what I deemed sub-par, due to being in an unmovable relationship. I have this new video series where I’m dealing with people and aspects of horror, I can say that. But trying to describe it would then lead to—I would not be able to freely move, to see where the video could go. When you start a project, there are unforeseen benefits that could happen, and the more you allow the project to guide you—at least, for me, I’ve noticed—there are moments of random brilliance.

If you put language down first, you’re boxing yourself in?

Not so much boxing myself in; I release a bit of the [possibility] of the project guiding me to where it could go.

That’s a subtle thing for someone to notice. That’s very aware of the process.

When I say I don’t think about it, I’m obviously always thinking about stuff, but I guess I never think about why I do anything.

Random brilliance?

Yes. Inconsequential brilliance.

Sublimation. That’s when energy is coming out of you—oftentimes a creative energy—from a place in the subconscious that may be unacceptable to your conscious mind. This could be related to what you are describing.

Maybe.

It’s something for you—it’s something for you to not think about.

Yeah, something for me not to think about. [Laughs]

You inspire me: I need to think less while making things. How did you go from music to visual art?

For the longest time it was just classical music and composing. Now composing and visual arts have inadvertently become my vessels. Not by my own choice, by coincidence. The turning point was when I was asked to write a piano score for “Nosferatu” at the Boise Art Museum. That was the moment I became not just a composer, but also a contemporary artist.

Nosferatu, the silent horror film about a vampire?

Yes. Terra Feast and Molly Deckart were people who entrusted me to write music for these big projects. I started to write music for the Idaho Horror Film Festival and that catapulted me further than expected; it changed my relationship to writing music. It became more cerebral, and that is also when I started to embrace randomness.

Before, did you avoid randomness?

The situations I was in kind of forced me to adapt, it was a very tight deadline: maybe a month. It seems now that I was in a state of mind I seem to thrive in. Just letting go, embracing the brilliance of unpredictable situations.

I find that does happen under an imposing deadline. Lack of time is a constraint that is oddly freeing. How was composing for film new for you?

It wasn’t so much the movie. It was more so me embracing my relationship with the film.

Was it about your response, about a dialogue?

Exactly. I was placed in a situation where I was forced to create an audio relationship with the music, that through melody, timbre, and tone would reflect what everyone was seeing [in the film.] I embraced the idea of having projects manifest on their own.

Sometimes over-planning a project will yield awful work. I’ve done that.

Yeah. [Laughs] It was trial by fire, because I didn’t have any time and I took the show very seriously.

What would a perfect day look like for you?

The perfect day is waking up at five-thirty or six in the morning, drinking coffee, maybe going for a walk. Sometimes I just sit right where I’m at and stare at the wall. [Laughs] And—. Honestly, I take it back. The perfect day for me ends with a bow. A perfect day for me begins and ends either on a stage or off the stage. All others are just days to work towards that.

Sharing your work is the pinnacle?

Yes, to perform my work, maybe with collaborators that I deeply love and respect; sharing that experience. To present art and music, to me, is a perfect day.

I like that.

It’s almost like a social acknowledgment of a selfish moment.

Selfish? When someone is sharing their art, I’m not thinking “Oh, God, you’re so selfish!” [Laughter] Right?

No, never. That’s the thing. I don’t associate selfishness with anything negative. I think our society has used the word “selfish” to deem a cultural taboo, but I don’t think the word itself has to have a negative connotation.

I kind of see what you mean.

To love is to be selfish, you know. I choose to love someone because I selfishly want them and their ideas.

It’s like a hunger. OK, I get it. I kind of love that, actually. I live in a world where I am surround by things that inspire me, that fill me up, that speak to me, and I want to EAT it all.

We all do, exactly.

If you are hungry, eat.

Completely.

East Boise

April 3, 2019