Creators, Makers, & Doers: Amy Nack

Posted on 4/30/19 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History

Amy Nack, artist and founder of Wingtip Press, facilitates community art projects that get people hooked on the magic of printmaking. She says it has something to do with the sound of tearing paper, of ink rolling on the brayer as it warms up, and the final surprise of pulling a print, a process she loves to share. She looks to history and a sense of place to create a meaningful framework for projects such as Print Boise and, coming in July 2019 to coincide with the Boise Greenbelt’s 50th Anniversary, Print Boise River. She invites you to experience the magic for yourself, to create your own edition of prints inspired by the river and the city of Boise—print one for yourself and print some to give away; it’s an element of printmaking she loves, one that contests the precious art object by virtue of printmaking’s democratic nature. Whether teaching or working on her own, Amy has learned to follow her intuition and trust that there is always something good on its way.

How did you get started in printmaking?

I had been in the paper and packaging industry for about thirty years, and I was working with printers and graphic designers but always wished I could be the artist. But I never had any formal training. I was looking for a printmaking workshop, after I moved to Boise, I thought it might be a way to meet artists. I ended up finding a workshop in Italy. [Laughs]

Of course you did. [Laughter]

I just thought, “What the heck?” I took a leave-of-absence from my job, and had a wonderful experience. I didn’t do such great printmaking, but loved the art history in Florence. I came back and decided I could take one class at Boise State, “Art of the Italian Renaissance,” but, I would walk by the printmaking lab, and peek in. The professor invited me in, “Hey, if you think you want to take this class, show up tomorrow and if one of my students doesn’t show, you can get in.” So I did that.

You signed up for art history, but deep down you wanted be in the printmaking lab?

Yes, I got into that class. At the end of that semester, I quit my job. I decided to enroll full time and get my BFA. I just didn’t think I could do a university class in printmaking, I was a little nervous about it, but the professor was very welcoming. I tell people all the time it was the worst financial decision I ever made in my life, but it was the most remarkable personal decision I ever made.

Is it worth it?

Totally worth it. I love it. I get bogged down because I’m an independent contractor; I get invited to teach all over, I run projects, I do workshops. I get overwhelmed sometimes, but I still can’t wait to get up in the morning, get in the studio and think of ways to engage people in printmaking.

What do you think was holding you back from taking that first printmaking course?

What held me back for fifty-five years?

That’s a good question.

That’s a really good question. Because I remember, as a little girl, when the Christmas catalogs would come, I always circled things like the jewelry making kit or the bead making kit or the soldering toolkit— always working with my hands. But I never felt confident because I’m not a great renderer of drawings. I don’t have the patience for it, but I love color, I love line, I love the surprise that comes with printmaking. There’s a mystery to it.

It’s a transformative process.

Right, it’s an indirect process, whereas painting, you’re putting the paint on the brush, putting the brush on the canvas, but with printmaking you’re putting your image on one surface, then transferring it to another surface. And there’s no accounting for what can happen when that transfer happens.

I wasn’t good at rendering realistic drawings either. I always thought I had to master that before I could be an artist, back in high school. Did you take art in high school?

I grew up in Minneapolis and we had an extraordinary art education; I remember, in junior high, we were working with sterling. That’s phenomenal.

You were doing metalsmithing in junior high!?

We had an extraordinary ceramics lab, too. Then in high school, my father chose all my electives because he thought I would, you know, need to be a secretary. I wasn’t encouraged to go to college. And I was never really encouraged to make things.

Were you able to find an outlet for making things?

We had a fabulous summer arts program at the parks in Minneapolis. There were arts and crafts, theater, softball. I would go down and enamel copper or whatever project we were doing that day.

Did you walk there?

Yeah, there was a cluster of kids from my neighborhood, some were not interested in the crafts, they were more interested in badminton or other things. We’d go in the morning, walk home for lunch, and then come back in the afternoon. That was in the ‘50s.

But once you were approaching the age to look at careers, art wasn’t an option?

No. In fact, when I finally did decide to go to school, I really wanted to study home economics, because that was one of the classes my father approved of. So I did all kinds of sewing and that sort of thing. I was interested in food science, there were all these food companies in Minneapolis: Pillsbury, General Mills, all those. But [laughs] I had a boyfriend that went to another school, so, like an idiot, you know, like a foolish young woman who was never really encouraged to think for herself, I guess, I just followed him. Of course, that didn’t last.

That seems to be a common theme for a lot of young people, today, or even fifty years ago. So, no art school for you?

That was fifty years ago? Oh, my God. [Laughs] For the ‘60s, yes, people went on to art school, but I guess I never had the confidence, and I didn’t know what I was doing.

I still don’t know what I’m doing half the time. But it is interesting because I’ve talked to a lot of artists, and, while many parents don’t start out supporting their child in the arts, as they go into adulthood, generally that latent support ends up being a rock for would-be artists to feel comfortable to forge a career in the arts. Then they say the same thing as you, which is, they wake up every day excited to get into the studio. How did your experience affect your own parenting?

I dragged my kids to every art class I could find—it wasn’t their deal, and that’s perfectly fine, you know.

No, it’s not. I’m dealing with that right now. It’s actually kind of irritating. You can lead a horse to water. . .

[Laughs]

Was your father strict?

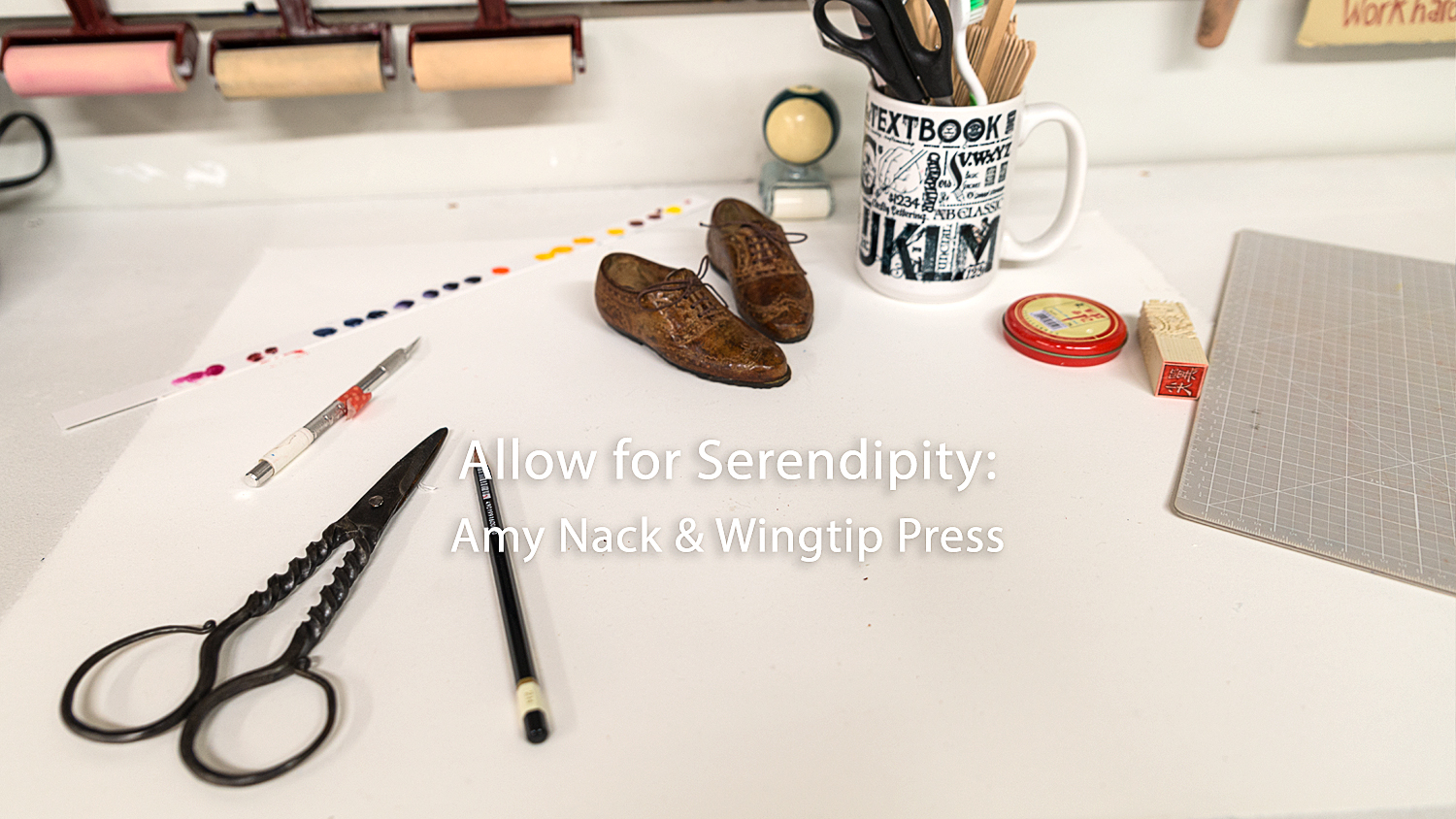

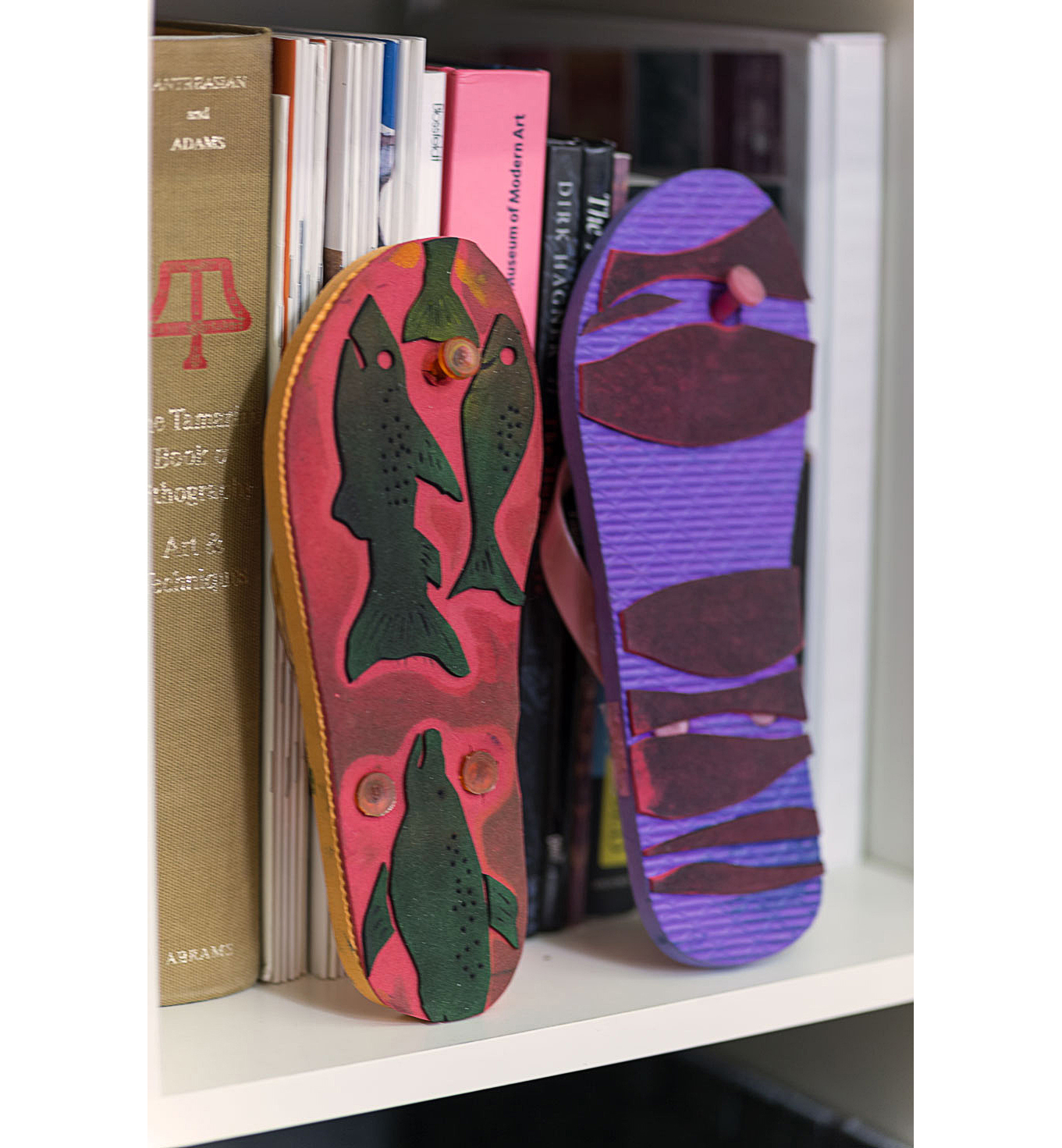

My father was a wonderful man; he was very strict, very formal. He and my mom both went to college, but he didn’t think women should go to college, that they’d up and get married and have a career as a housewife. So he didn’t encourage me. I know that he was proud of me afterwards. That’s—WingTip Press is named after his shoes.

Ah, I see. I was looking at the little sculpture of shoes you have on the work table.

[Laughs] My mother polished my father’s shoes every Sunday on the Minneapolis Tribune. He was an executive and went off to work, always dressed very professionally.

Did he wear starched shirts?

Oh, my gosh, yes. He was a very proud dresser. He wore really wonderful wingtip shoes. When I decided to open the press, I thought, the name is going to be Wingtip Press.

What an honor! It’s interesting how parents, they can be hard on you, but—sometimes that makes the bond stronger, and you want to honor them.

I really do.

That’s really very touching. We are looking for tissues, we don’t have any tissues in here. Oh, well. People are funny; he married a woman who attended college and was probably drawn to that. But he didn’t outwardly promote it for you. People can hold two different ideas an the same time—

That’s exactly right. It isn’t binary.

I just am so happy to know the history behind the name Wingtip Press! Did he know it was named after his shoes?

No, he died when I was pregnant with my son, who is now thirty-five. He was proud—I did very well in the paper and packaging industry. I was making really good money back then. But I just got to a point where I hated to go to work. I loved the people, I loved making the connections, all that.

It’s interesting that your professional career was centered on paper, and your printmaking work is too. But you hated the job. You’re an extrovert?

I’m an extrovert; I can be by myself for hours and hours and even weeks at a time, but finding a way for people to feel connected, that’s important to me.

Do you get cabin fever if you work alone too long in the studio?

I think one of the reasons I love printmaking is because it’s so collaborative. You’re sharing equipment, you’re making multiples. It’s a democratic process, it’s made to be accessible. [Historically] they made prints because prints were more affordable than paintings. That’s my ethic, I think.

Why do printmakers share equipment?

You’ve got a six hundred pound press that costs six thousand dollars. Most people can’t afford to have one in their home. And if they do, they’re not using it twenty-four hours a day.

I makes sense to maximize its use. It’s a huge investment, both physical and monetary.

I think printmakers are more collaborative by nature; I’ve talked about this with other printmakers, we haven’t really figured it out exactly.

How did you get into teaching?

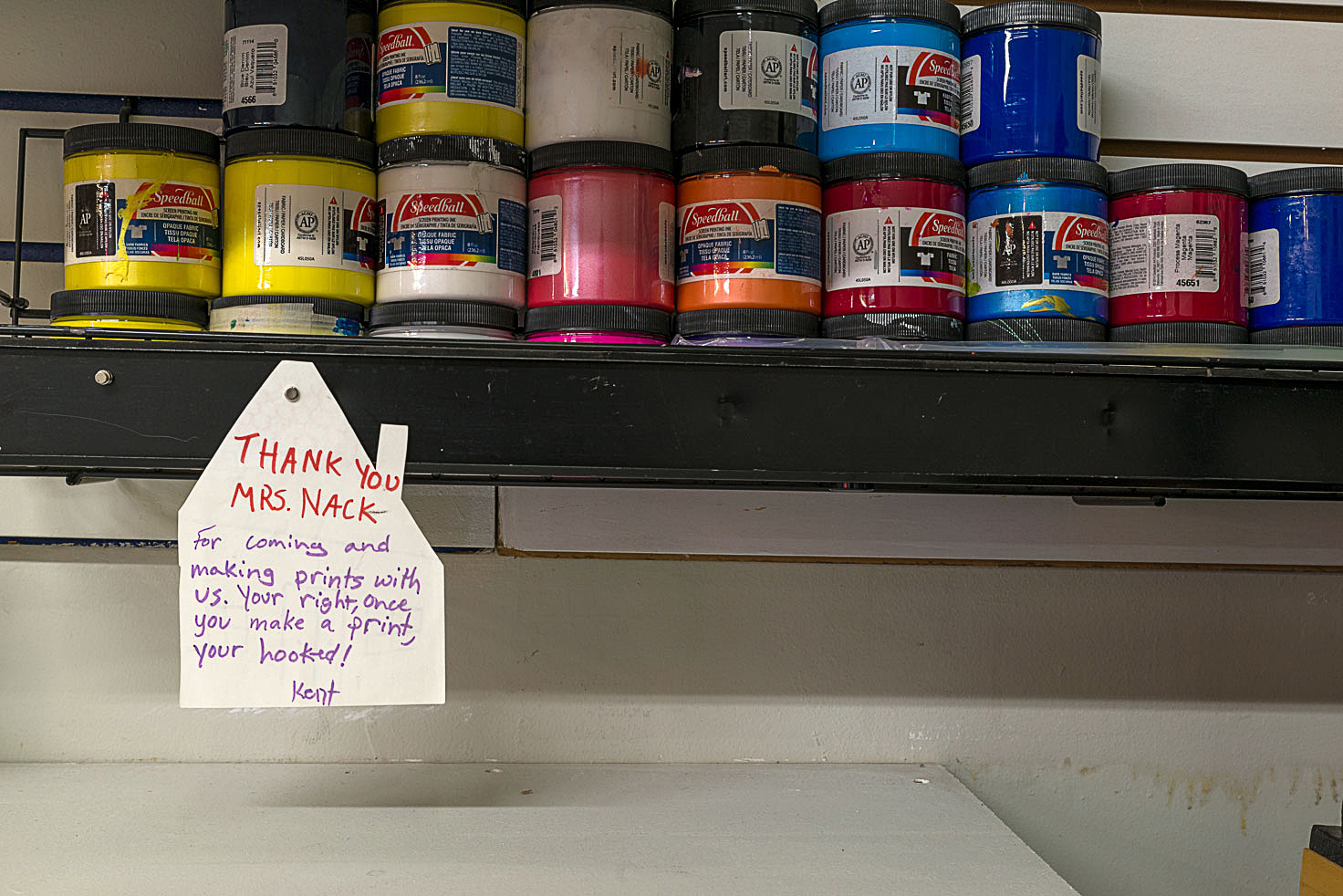

Because I didn’t have any income after I graduated, I became a teaching artist with the Idaho Commission on the Arts, I traveled all over the state and into schools for a couple weeks at a time and worked in a community setting. The one thing about printmaking is, you can work with a group, a community of people and they can each contribute and have a print to take with them. They are not making art that’s going someplace else—

Or that they will never see again?

They don’t walk away and keep it, meanwhile no one else ever gets to appreciate it.

A print for them, a print for you, a print for, whomever.

It’s very democratic.

When you quit your day job to pursue art, did anybody ask if you were having a mid-life crisis?

[Laughs] No, I really got a lot of encouragement. People saw it as brave. I don’t know that it was brave—it was almost desperation. Just, “I cannot do this. I cannot do this marketing business any more. This is not me.”

I feel like sometimes the best changes come out of desperation. I almost don’t know any other way.

I think so, too. I have younger friends who sometimes have a [limited] perspective, maybe something horrific happens, but because they can’t stand back away from it yet, they don’t see that all the growth happens in those problem times.

When life takes an unexpected turn?

And it feels like it [lasts] forever. But something good is always on its way.

It’s wonderful to be in a place where you can ride the wave and also realize it’s a wave. Not that I’m there. When things don’t go as planned I freak out and think my world is ending. [laughter]

Well, you do feel like that. When my marriage ended, my company knew it was a tough time for me and there was a position open out of state, they said, “Would you like to go to Idaho?” I thought, “Why not? Let’s try it.”

You just up and left?

I did. I was excited about it. Then I fell into the same old job and the same old—

Same sh*t, different town?

[Laughs] Yeah, exactly.

But then you up and left that job to enroll in art school full time! Finally! To become an artist!

And I still don’t feel comfortable saying I’m an artist. It’s that impostor syndrome.

Why?

I hold myself to a standard of artist that I really admire. Clearly I am a teaching artist, I just love introducing people to the printmaking process.

The first time you pull a print, it’s kind of like magic.

The magic, I really love that. I work really hard to find a way to make it accessible for people.

You take all the materials and teach workshops in public schools? How can I get you to come to my kids’ school?

The classroom teacher can apply for an artist-in-residency at the Idaho Commission on the Arts; there are educational grants to bring in teaching artists; ceramic artists, saddle makers, creative writers, painters, printmakers.

Do you think a teaching artist is different from a regular artist?

I think there’s a sort of a hierarchy in some people’s minds. I like dissolving those hierarchies. I don’t live well in a hierarchy. I know that what I do is artful, my ideas for teaching, but is it something I’m personally rendering that I’m putting on a wall? No.

So you are thinking of the actual art object, the work as a measure of a certain type of creativity, and teaching as another kind. What is your approach to teaching?

Trying to find ways to engage people in learning and making art at the same time. It started with a question: how can I engage people in something I love—and it’s not—it’s not fluff? It’s meaningful.

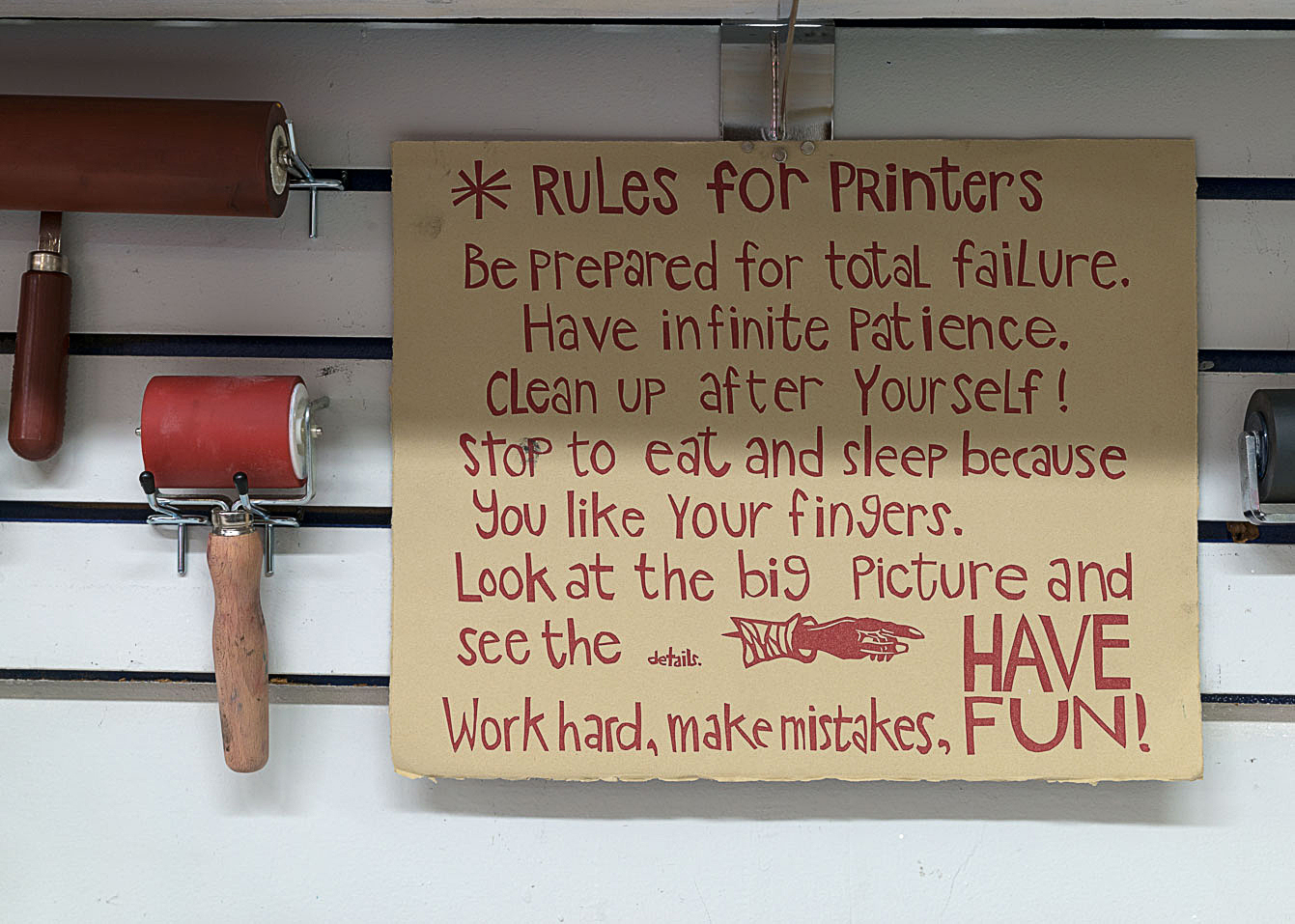

What do you love about printmaking?

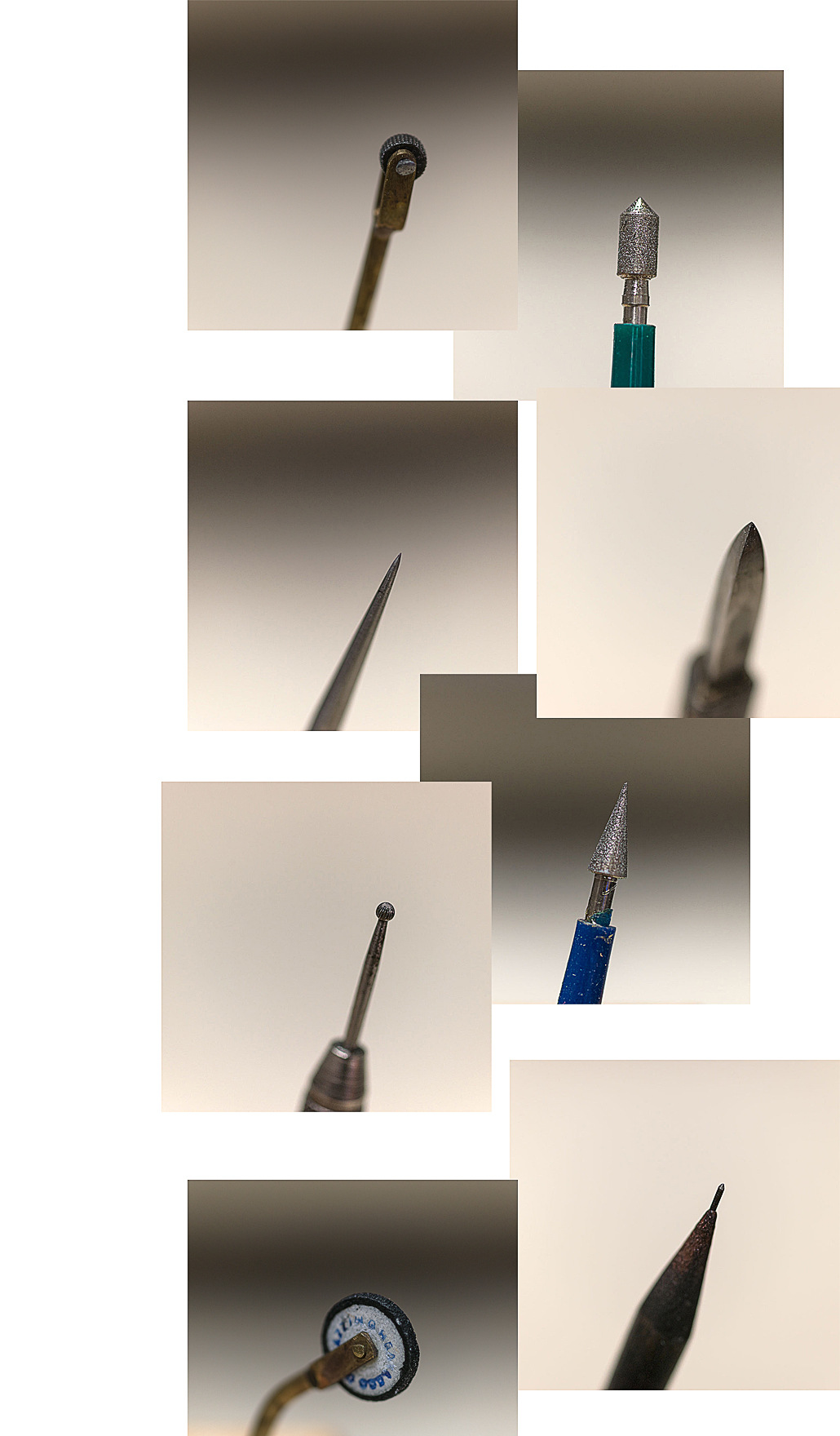

It’s so process-driven; you open the ink, you smell it, you’re blending it with the palette knife, softening it. Then you’re rolling it and hearing the sound of the brayer. You’re transferring and cutting—you’re measuring your paper and doing all this math and figuring out all the details at the borders and the margins. Then you’re soaking the paper, blotting the paper. Finally you’re grinding the press, to get that print to come through.

It’s very sensory. You can get so focused on the process that your mind frees up.

And [the final image] is always a surprise. You can plan—the best printmakers are pretty good at predicting what their outcome is going to be, but monotype and other methods really allow for serendipity, [working] intuitively and responding.

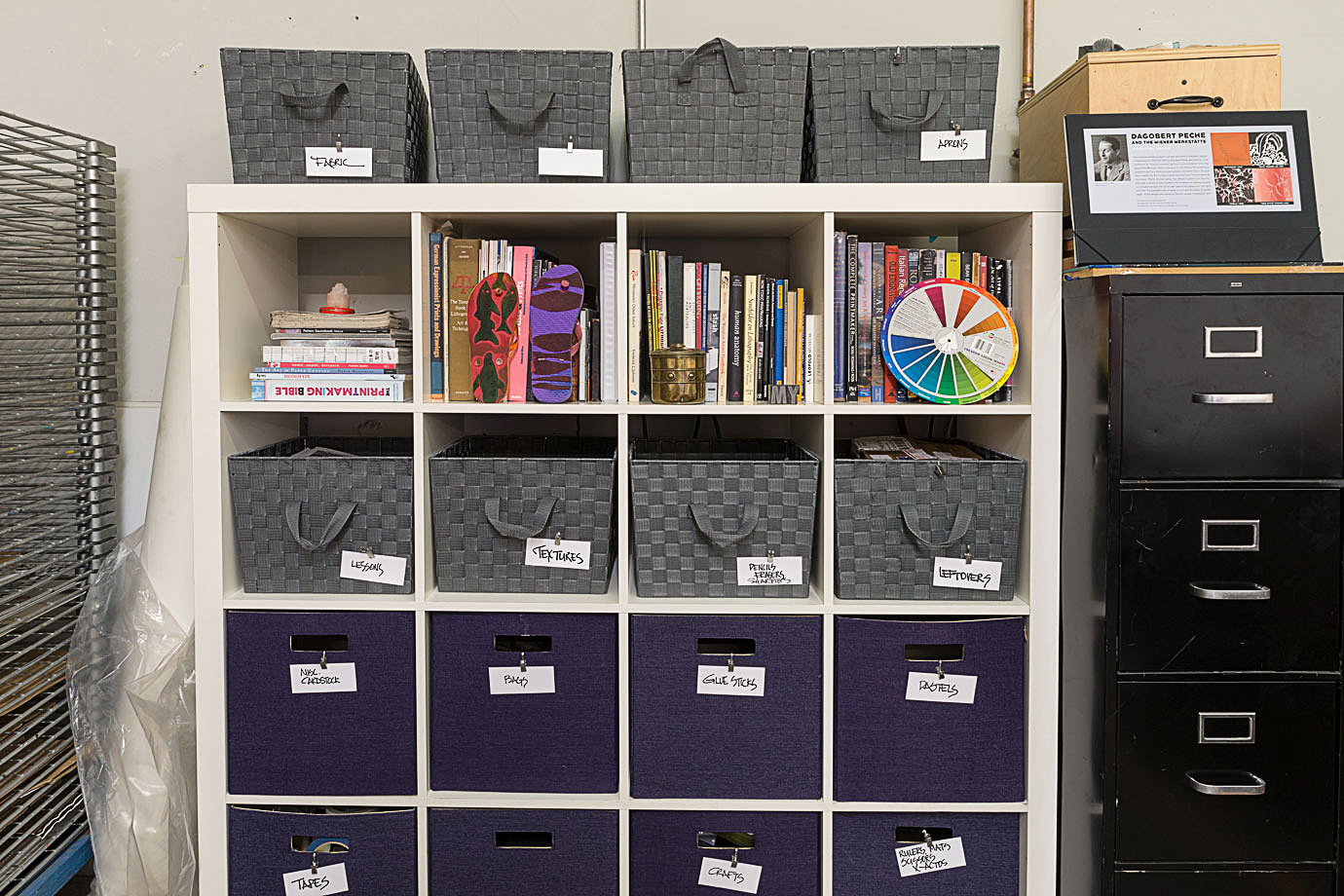

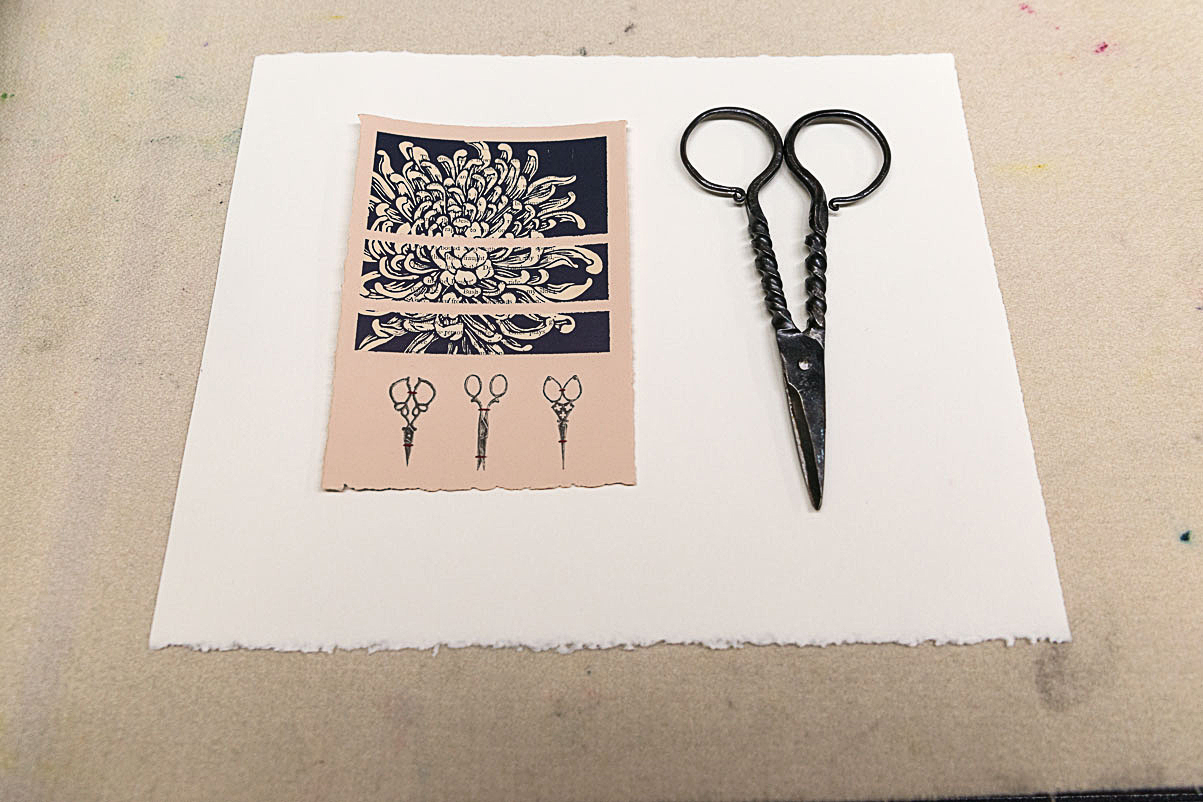

Responding to what’s right in front of you. I can see that it’s important to you that the work is meaningful, like the Print Boise project; you took people and students out to neighborhoods, learned a little history and made prints of homes in our community. I think that’s very meaningful. We also need to talk about the Leftovers print exchange. Printmakers use great big sheets of high quality papers, some of it can be very expensive, but you don’t always use the full sheet. So you cut it down?

You tear it down because we love that deckle-y edge of the paper. So, if you are making prints to fit in a frame, say sixteen by twenty, you have scraps.

Scraps of perfectly good, beautiful, expensive paper?

I was cleaning out the flat files at Wingtip and had all these precious scraps of paper, and thinking, “I can’t be the only one that has this problem.”

Why don’t you throw them out?

No, you can’t throw them out, because you might use them for something, and they’re cotton rag papers, you know; I mean, they’re beautiful. I had been involved in a few print exchanges and thought, “This will be fun, to do a print exchange where people just use their leftovers.” I invited about twenty-five people and I think we got sixty people the first year. The next year it was close to a hundred and we had people from all over the world.

It is kind of a chance to play. Because it doesn’t have to be a part of a larger body of work, and because of the forced paper size, working with scraps.

Right. It’s a chance to play. Some of the artists take it really seriously. Some people love the idea of getting a dozen random prints in return. Our second year we got an inquiry from New Zealand to show the prints. Then we got inquiries from universities to show them, and a request from Wales. Not only do people get prints in return, they get all these global locations on their resume.

So after an artist has sent you their edition of fifteen prints, you send them back a selection of prints from other artists?

Yes, twelve random prints.

And they get to build their art collection.

In our second year I decided to partner with the Idaho Hunger Relief Task Force to have an auction to raise fund for the people they serve that don’t necessarily always have leftovers.

Food leftovers?

Yes, they are an extraordinary agency working on food security for all Idahoans, and despite that it’s only serving people in Idaho, people from England and Wales and Australia and New Zealand and Singapore and Finland and Germany all think this is still a good idea and they support it by sending us their work.

Leftovers is coming up on its tenth birthday, happy birthday!

I’ve often thought about having an exhibitions of ten years of prints.

That would be, like, a thousand prints.

It could be a thousand prints. The most people we had registered one year was a hundred and eighty. Some artists have done it all nine years,

What are you working on now?

I’m doing Print Boise River. Wingtip has been doing the Print Boise thing ever since we had great success with the 2013 sesquicentennial celebration. That launched Print Boise II and III with a series of “plein air” print workshops downtown and places like The Depot, the Idaho Pen, Boise High – Boise landmarks. We partnered with Preservation Idaho and Amy Pence Brown provided the historic background on each location and then the groups took to the streets with inked brayers and paper to do “rubbings” of architectural details and surfaces – capturing textures from brass plaques, signage, really anything with a relief type texture. This year we were thinking of new ways to engage the community with landmarks and printmaking so we chose the Boise River.

The Greenbelt is having an anniversary too! Fifty!

Yes! And Print Boise River is a new twist, we’ll have people create images of river life on stamps that adhere to the bottom of a flip-flop. They’ll walk over an inked surface onto a 150′ paper “river.” The Idaho Conservation League will join us to share info about river quality and the libraries will be offering a series of free workshops. Our big event is July 13 at the Anne Frank Human Rights Memorial. A clean river and water is a fundamental human right.

That is so cool! You’re cool! I didn’t know you could do printmaking with flip-flops. Your projects are very unique.

[Laughs] I’m happy with what I’ve done in the community and I’m happy that people still come use the studio. It’s given me opportunities I never would have had before. I got invited to teach in China last year. A woman I knew at Boise State was teaching over at an international school and the school had a printmaking lab. The art teacher said, “You know, I’d really like to learn how to use this equipment.”

Oh, they had a lab but couldn’t use it?

They had the equipment but didn’t know anything about printmaking. They flew me over. I got a visa and taught for two weeks. I brought Leftovers and showed the prints, now we’ve been on three, four continents.

That is a huge achievement. You’ve built Leftovers up into an international exhibition. Do you have projects in the back of your mind, that you always want to get back to?

I do. I want to start making my own work.

This comes up so often. Because as artists, sometimes it’s easier to facilitate an event or exhibit rather than focus on our own work. We always have plenty of ideas, but—

It’s still the matter of sitting down and putting those marks down.

I have a lot of things brewing that haven’t got any marks put down. What do you think, in five years, what do you see?

What I’d like to see is some sort of legacy for WingTip Press, maybe I’m going to have to look at a nonprofit status to make sure that happens. I’m not ready to do that right now, but I want it to be available to other people. You know, it’s precious equipment.

Not just the equipment, but everything you’ve learned.

That’s all my teaching. That’s what supports WingTip. But—the only way you’re going to sell art [in education] is if it can meet some of the standards and be cross-disciplinary with math or science or reading, the core subjects. That was a benefit of being a teaching artist for the Idaho Arts Commission. I learned how to do that.

When you say “sell art,” you mean to make it a priority in schools?

Yes, sell it to educators.

And say, “Look, art is important because it engages students in math and science in new ways and it makes education richer.”

Yes, they’re using design skills, creative problem-solving, math, writing artist statements, maybe looking at the ecology or history. The students are engaging all these core subjects and we’re using art to do it.

I think you need an apprentice.

Yeah, I do need an apprentice.

The amount of wisdom you have is precious. It needs to continue.

I agree.

Downtown

May 1 , 2019