Creators, Makers, & Doers: Return of the Boise Valley People

Posted on 6/5/19 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History

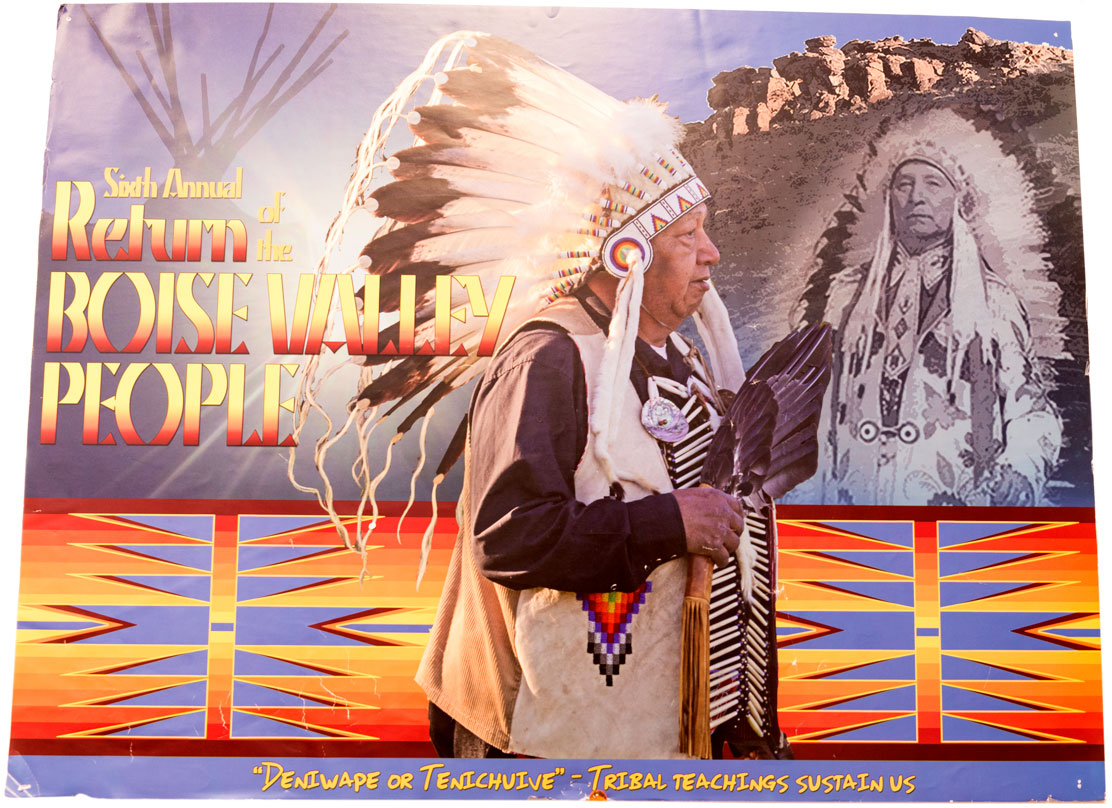

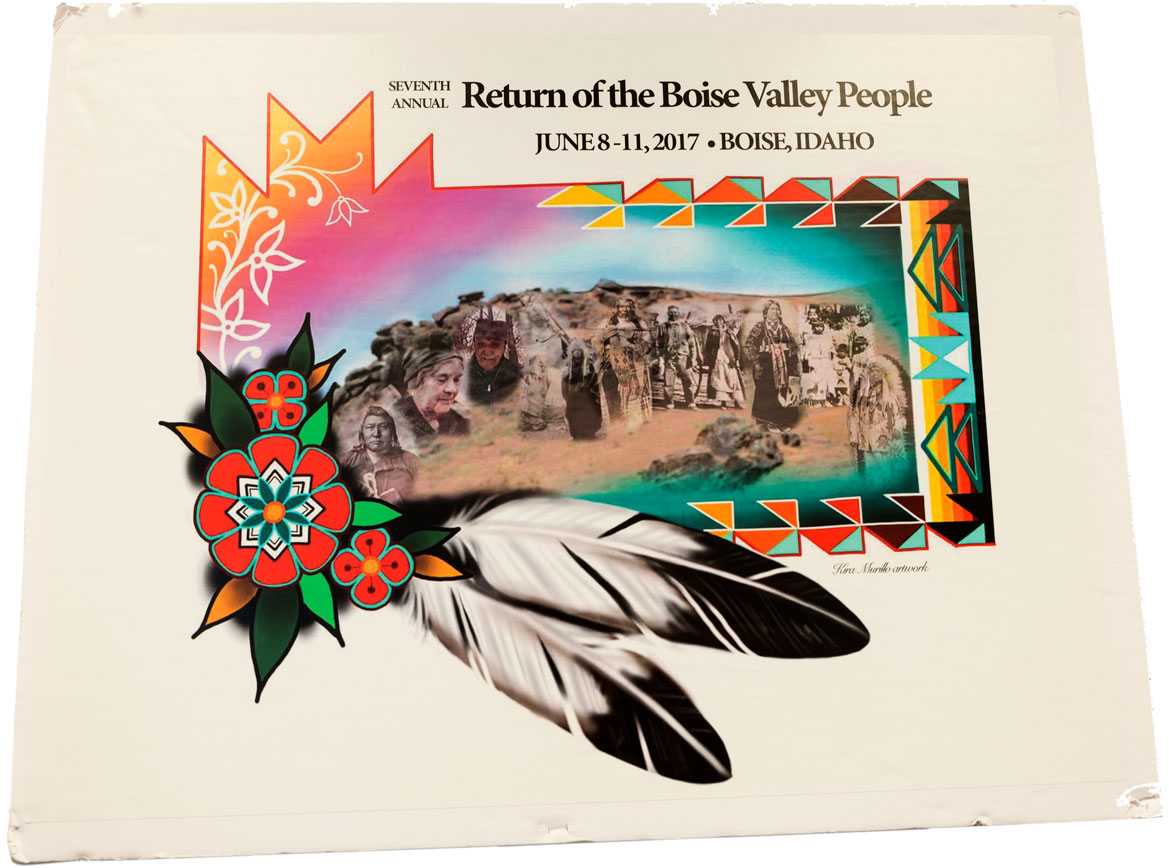

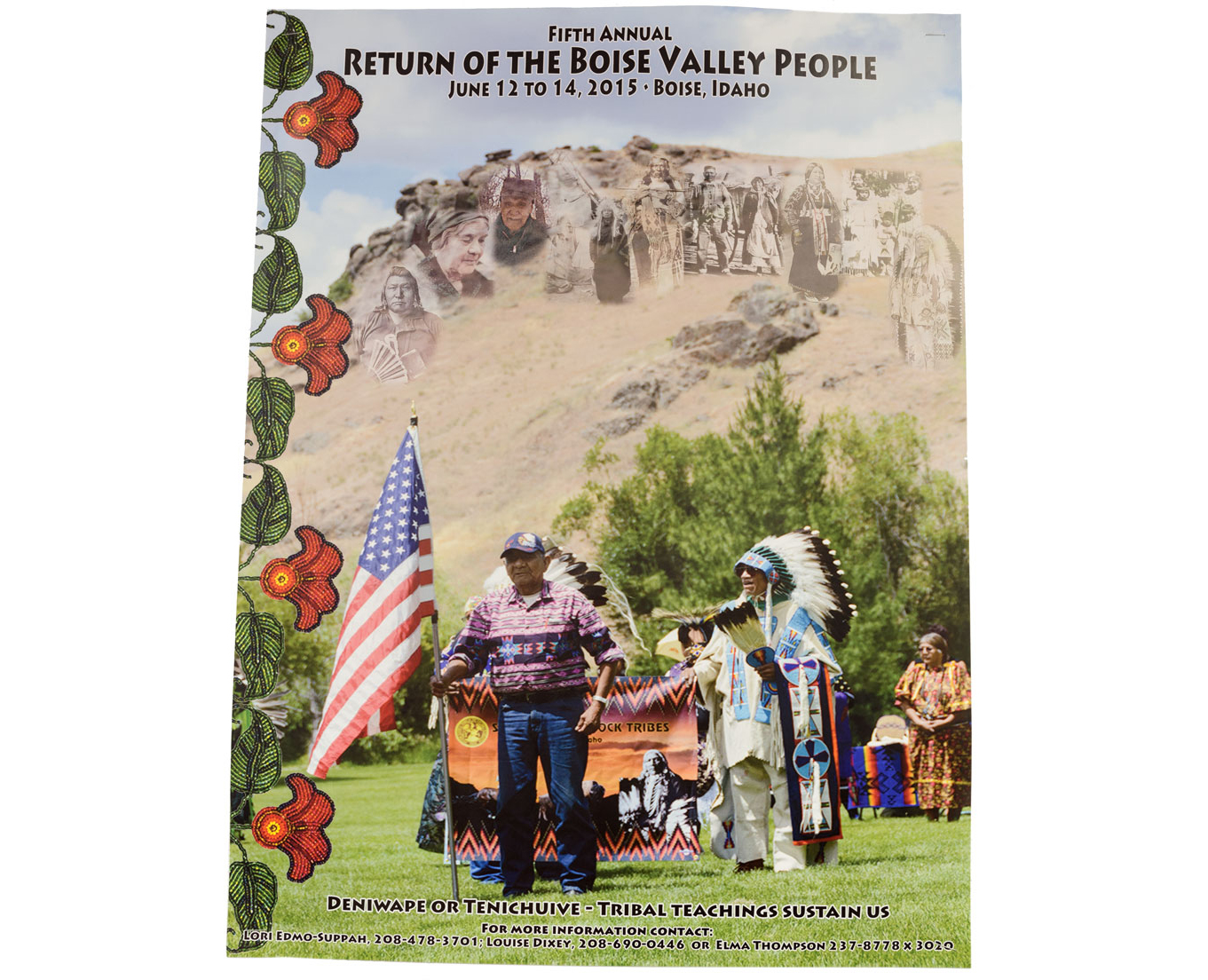

Return of the Boise Valley People is a gathering of the descendants of the original inhabitants of the valley for sharing culture, oral histories, and of course, food. This year will also mark the renaming of the former Quarry View Park to Eagle Rock Park and Castle Rock Reserve to Chief Eagle Eye Reserve. We spoke with event organizers Louise Dixey, Lori Edmo, Verna Racehorse, Brian Thomas, Justina Paradise, and Kenton Dick about the history behind the event and the significance of the location. We spent time at Fort Hall learning about the grassroots effort among members of the regional Tribes, including their aim to ensure younger generations and the public know their history, and that the wishes of their ancestors be fulfilled.

Who are the Boise Valley People?

Lori Edmo: The Burns Paiute of Oregon; Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs; also of Oregon, the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone of Nevada; the Shoshone-Paiute Tribe of Idaho and Nevada, along with the Shoshone-Bannock of Idaho.

What is the Return of the Boise Valley People Event coming up?

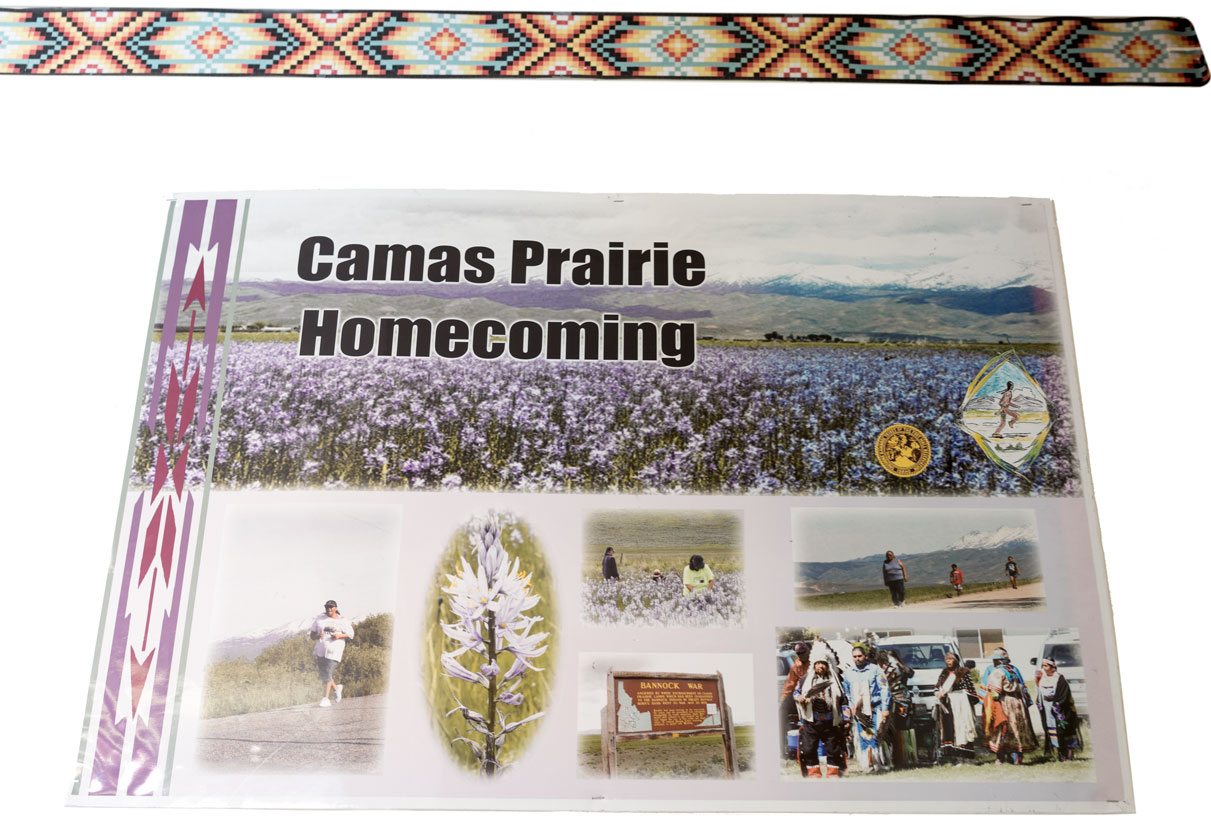

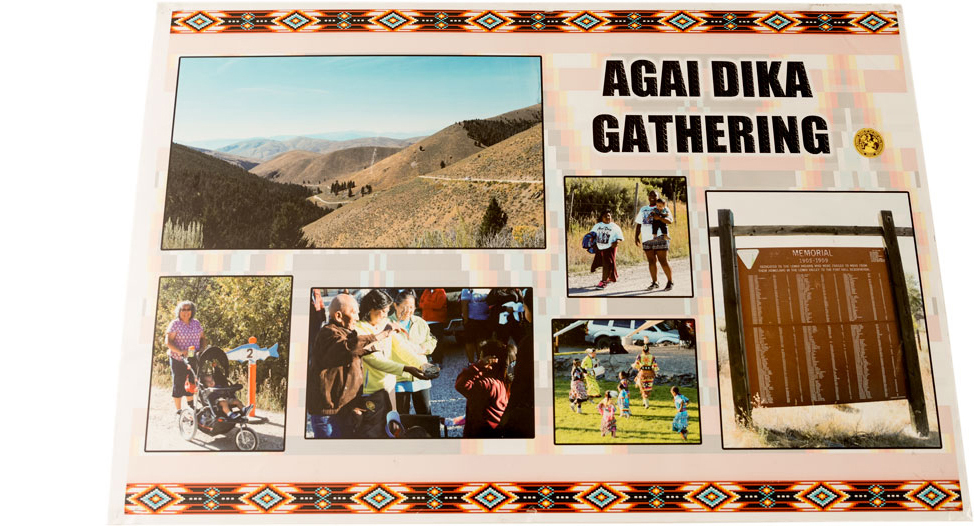

Verna Racehorse: It’s a unity gathering we started nine years ago to bring the descendants back to the Boise Valley. We have two full days of activities and sharing. June 14th this year will be open to the public; we have a milestone to dedicate, with the renaming of the park. We will also have displays set up to educate the public on who we are and where we came from and what we’re doing. We come together for oral history, community, socializing— sharing our cultural foods. Each tribe does a lunch or dinner and shares their cultural foods.

Are we going to talk about the groundhog?

VR: Yeah, Jake’s crew digs a pit and gathers all the sagebrush, and we have people teaching how to prepare the groundhog and bake it underground. [It bakes for] five hours or so? It’s ready by noon—for lunch.

What does it taste like?

ALL:Chicken. [Laughter]

VR: Very greasy, just very good, it’s good to eat it with bread. You’ll just have to come and try it.

Lori called the event a reunion, do you think of each other as extended family?

VR: Yes, right. We have cultural games for the children and classes to educate our youth so they know where they come from and where they’re going. If you know your roots, you are adjusted better in life, as you grow up. Making sure that our youth are involved [is important.] Every morning we start with a sunrise service—when the sun comes up over Eagle Rock Park.

About how many people attend?

VR: Approximately four hundred people—it wasn’t that many in the beginning. It’s grown.

Why is Eagle Rock Park significant?

LE: That’s where a lot of our ancestors are buried, all along there, and throughout the whole Boise Valley. We come back there to pray for our people. It’s really significant because the [geothermal] water is important, too—before it was covered up, when it was open, our ancestors used to soak there.

VR: Brian was talking about spirits [laughter]; we have good spirits [at Eagle Rock Park] and it’s a good place to go. Even today, since I live in the Boise Valley, I sometimes have difficult times and I go there to pray and I feel the presence of the good spirits. It’s a good place to get grounded, drink my water, reflect. And it’s powerful. It’s a really powerful area and a good place to take the kids. There’s a park, you can run around, throw a football, whatever, but it’s a good place to go back and pray.

Brian shared something he learned about the spirits when I asked whether an encounter is spooky; he was told by his elders that the spirits can’t hurt you, it’s the people who are alive that hurt you. That’s pretty poignant. I was able to visit Louise in her office at Fort Hall; she has a poster that says, “Still indigenous. Still here.” That made me stop and think, what would you tell someone who thinks that the tribes are a thing of the past?

LE: That it’s is all about what you read in the history books, and it’s written from a white perspective. The bulk of our history is oral history, so you don’t see it or study it in school. We’ve always been here, that’s why we’re the original Boise Valley People. And we’re never going to go away, that’s why it’s really important that we name these areas in honor of our people. People don’t know the real history; we have a lot more work to do. This is only the beginning.

I have to admit, I don’t know a lot about that. I could use your help.

LE: Yes, exactly, our eventual goal is to build a cultural center. Every other ethnic group in the state of Idaho has a cultural center, except us, which is really crazy because we’re the original people of this land and we should have been first. But everybody thinks about us in the past because of how it’s written in the history books or they think, you know, we’re mascots. And we’re not. There’s no honor in that. It’s a matter of respect. To respect our people and honor our people and share the real history of this area is important.

I think so too. Jake, tell me about your involvement with the Return of the Boise Valley People gathering.

Jake Fruhlinger: I’m the cultural resources manager and tribal liaison for the Idaho National Guard. There are laws and regulations stating that agencies have to work with tribes, and what I’ve seen, unfortunately, is that most agencies do the absolute bare minimum. Our leadership realized we need to go above and beyond: why not establish, maintain, and build relationships that are long-lasting? I was really lucky with our first adjutant general, General Gary Sayler, and our current general, Mike Garshak, because they support this event and the relationship. I was asked, “Hey, would the National Guard be willing to help out?”

You were asked to help the second year of the Return of the Boise Valley People? And you provided the location out at Gown Field, and the kitchen, free of charge?

JF: Yes. My leadership has allowed me to explore various programs and build a path with the tribes, letting them know we’re here to build a partnership. Our role is in opening up some facilities and trying to facilitate as much as we can. I remember being told by Lindsey Manning, a former chairman from the Shoshone-Paiute tribe, that a lot of the tribal elders and leadership talk about the irony; because it was the military who originally marched the tribes out of the Boise Valley and put them on various reservations, and it’s ironic that they are now the ones opening their arms up to help bring everyone back together. I was told that some of the elders didn’t want to come to that first event at Gowen Field, because it was their grandparents who were marched off, and they, rightly so, had a certain perception of the military.

LE: What’s so amazing about this event is that the elders really appreciate coming; and they like to visit and speak in our language. One of our Paiute relatives from Warm Springs, who’s gone now, told me she was so amazed because it was the largest group of Paiutes she’d ever seen in one place, it really made her happy. It’s about fellowship, seeing our relatives and meeting new relatives.

But it must have been difficult, at first.

LE: When our Grandma Lucy finally went over to Boise with us, after we convinced her in 1990, for the Idaho Centennial, it was hard for her because back when they moved us out, the Cavalry, they were mean, and they killed a lot of our people. A lot of our people were hanged. That mural in the Ada County Courthouse, the old one, that’s real.

Was the mural removed because it depicted two white men preparing to lynch a Native American? The one painted in the 1940s?

Louise Dixey: It wasn’t removed. The tribes insisted that it be kept there.

LE: Because it did happen.

LD: It was the truth.

That’s important.

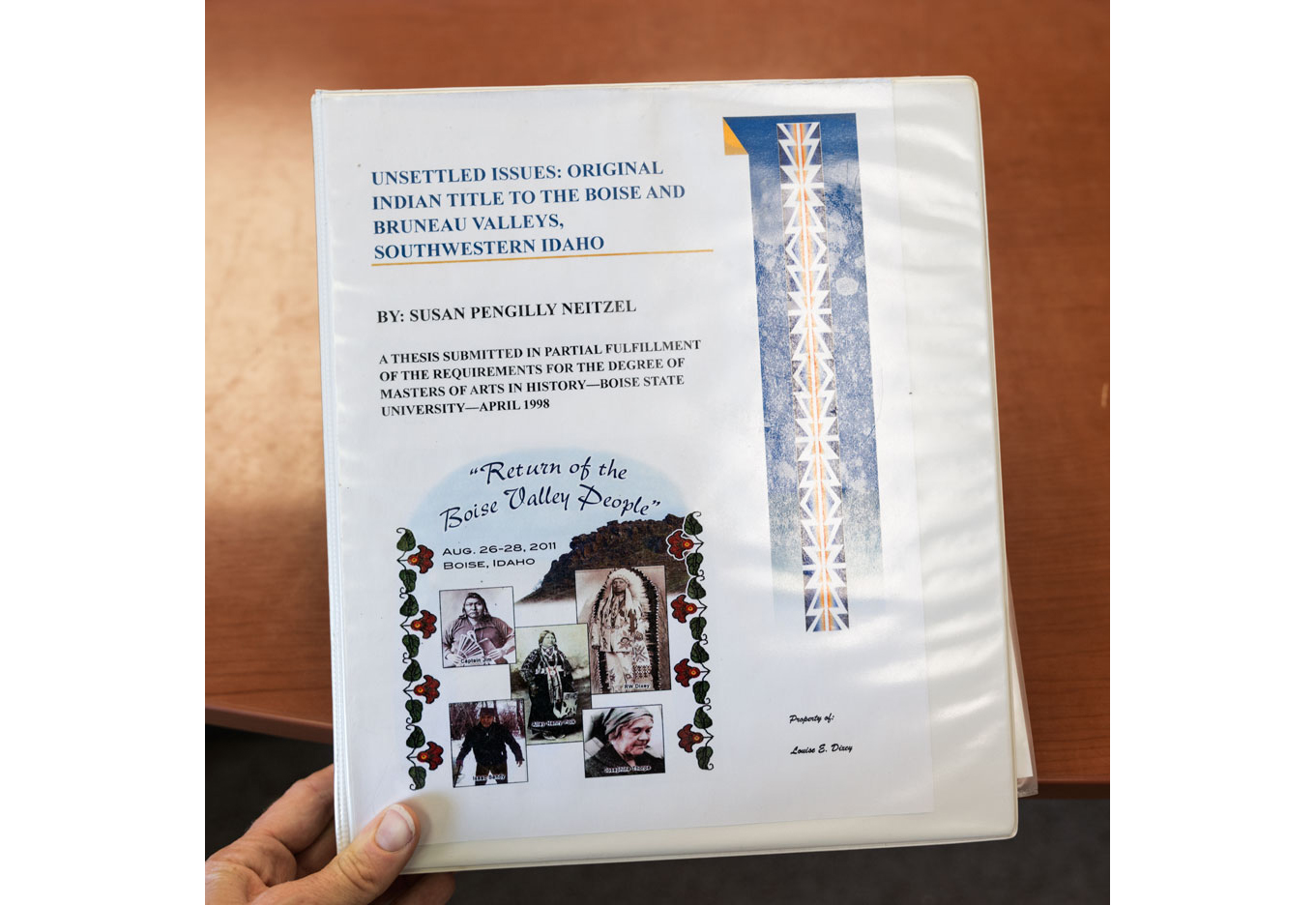

Justina Paradise: Our elders used to come here from the Sho-Ban Tribe and Duck Valley and McDermitt and Burns and talk about the treaty that was written that was never ratified. That was in the ‘50s and the ‘60s. Our old people used to talk about that, because [that information] was passed on orally to them.

LE: Because the treaty wasn’t ratified, then we still own title to the land. And people don’t want to admit that.

LD: There’s the Boise Valley Treaty that’s unratified, the Long Tom Creek Treaty that’s unratified. A Bruneau Treaty that’s unratified, all calling for us to give up that area. They were all Caleb Lyon treaties, and none of them were ratified. We had our mom’s copies of our great, great, great-grandpa’s documents that showed that they were escorted out of Boise and that it was his homeland.

LE: They are original military documents; they’re over a hundred years old.

LD: We knew that we had every right to go back there, because the Indian Claims Commission did not settle the legal title of Boise Valley. They had this crazy concept that you had to prove exclusive use of a territory to make a claim for it, but that was not exclusively used by one group; it was all our different tribal bands that used that area. So, that’s why the title was never settled. And still hasn’t been settled. The Boise Valley Treaty guaranteed us a reservation there, and we never got it.

What about the re-naming of the park?

What about the re-naming of the park?

LD: When the Eastside Heights development was happening, in 1996, our tribe took a whole busload of people over there to testify against that development because they knew that’s where our ancestors were buried—up on that hill.

You literally stopped that development in its tracks?

LD: [Our] Dad [Kelsey Edmo] was the final one to testify, he said, “You know, the City of Boise and you, Mr. Kempthorne, should be embarrassed and ashamed of yourselves. You dug up all of our people out of that area and you need to make sure you do the right thing and put a stop to this development.” But if you knew our dad, he had a really gruff voice and he wasn’t afraid to speak up. [Laughs]

LE: Back in 1996, our elders, like my mother, Maxine Racehorse, wanted to push this through, this Memorandum of Understanding.

It was a Memorandum of Understanding between the city of Boise and the Tribes about the intent to rename the park?

LD: It was signed in 1996. Not only did it call for the halt to the development of that area, that we now are going to call Eagle Rock Park and Chief Eagle Eye Reserve, but it also set aside our continued use of the park, without charge. We were also to have the trails renamed in our names, and have the areas named according to what the tribes recommended, and there would be no further development in that area.

LE: It was signed in 1996 and said specifically that the renaming was to be done at that time, but it was kind of pushed by the wayside and nobody ever brought it back up

How did it get brought back up?

LE: We found out that once a month the Mayor meets with constituents in City Hall—you can get ten minutes with him.

LD: I gave Mayor Bieter a PowerPoint presentation all about our Boise Valley, about the unratified treaties.

So you sat down to educate the mayor. Were you nervous?

LD: No—I’ve presented before the Senate Indian Affairs Committee in D.C., spoken before the Northwest Power Planning Council. I’ve represented a lot of people as an advocate.

Of course, you wouldn’t have been nervous. [Laughter]

LE: So, we went in and got our ten minutes. [We brought] the records out—I advised [the mayor] nicely, that our next goal was to rename Quarry View, officially name it Eagle Rock Park. He said, “Okay.” So, that’s what we did.

LD: Because of all of that, the tribes made sure to get it in writing, we wanted to make sure it was fulfilled.

VR: Last summer was our first year having the opening ceremony right on the steps of Boise City Hall. We’re making progress. Nine years ago, we couldn’t even get in the office. But that is what our older people prayed back then, that someday it will come to this. And it’s happening. Long process, but it’s here today.

What are some of the challenges you face?

LE: We’ve spent hours and hours and a lot of money. There’s a lot of cost involved, most of us travel to get here. That first year of the Return of the Boise Valley People, we rented the education facility at Barber Park, and it was very costly. I don’t know how we paid for it all but it ended up being more than ten thousand dollars to rent that facility. But it’s worth it, or at least it is to me because, this is what our ancestors and our elders wanted. That’s who we’re doing it for.

Brian Thomas: The mayor has done a lot of good for us—and City Council, the Parks committee. We’re here today discussing [the event] and something I’d like to see is the indigenous people, the people who used to live here, put teepees up overnight, to show our presence. [The mayor suggested] we do a walk over to the State Capitol, and have a talk about our people, but it would be really nice to set up a teepee overnight or over the weekend at the park by the State Capitol. Or to have a teepee set-up challenge between the five tribes, for the public.

That would be really cool.

BT: The way the five tribes got disbanded, by going to the prison camp in Fort Simcoe, had a lot of our people separated in different directions. Some of my family members probably ended up in Warm Springs, Burns, and clear into California, Fort Bidwell, Yakima. Our great ancestors were the warriors and they survived, along with Verna’s great-grandmother. They’re the ones who told us the stories. I’m proud of my people, in this setting right now today.

What are you proud of?

LE: That we’re able to come together and work toward one common goal. That’s why I say it’s the five united tribes. Another thing is that we’re all grassroots people. I call us worker bees. [Laughter]

This is a volunteer effort. How will you know, going forward, that you’re making the difference that you want to make?

Kenton Dick: Our presence. History has shown that the Indian people have always been discriminated against, and even, you know, killed. “A good Indian is a dead Indian.” They tried to do that with us, with the Northern Paiutes, by gathering us up in the middle of winter and sending us up into Fort Simcoe. At that time, some of the people ran away and never got captured and stayed in the Drewsey, Oregon area. They tried to get rid of us because they wanted the timber, the gold, other minerals.

Mining?

KD: Mining, yes. They wanted to get rid of the Indians and the best way was just to move them out. They kept people in Fort Simcoe for a while and eventually had to let them go because it was costing them money. They scattered. The majority went back Harney County, some lived around the city of Burns and Hines. They didn’t live in town; they lived on the outskirts. They lived in tents, they built their own little wikiup to survive. They made hides, did beadwork, and made the gloves that the ranchers liked, and wanted. So we survived. My families came this way; they said they used to camp along the Boise River to hunt and fish, and visit other tribes. It’s important that we continue and teach our young ones about our history. It’s not written down. It’s handed down verbally: my grandparents telling me and my brothers and my sisters, and we in turn share it with our kids. We talk about [planning in terms of] seven generations. You go back three generations, to see how they operated. And you’re the current generation, so you plan for three generations ahead of you: your kids, and their grandkids. That’s how I look at it.

What do you see for the generations ahead of you?

For this group here, one of the goals is to have a cultural center. Like Lori said, we’re the forgotten people, but in time, people will remember us, remember that we’re here. That they didn’t kill us. We’re fighters. We’ll get old and die away, but we have our offspring who will continue that fight. We’re resilient.

Boise, Fort Hall

June 12, 2019