Creators, Makers, & Doers: Carrie Quinney

Posted on 1/9/20 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History

Carrie Quinney, a recent Master of Fine Arts graduate from Boise State University (2018), took a risk, walking away from a desk job (see ya!) to make art the center of her life. We spent an afternoon chatting in her mid-century home and enjoying the sunset (the light was gorgeous, though Carrie jokingly calls herself a vampire). She speaks about immersing herself and her work in the cultural transition from analog to digital life. It is a distinct point in time that affects generations born before the internet boom, stirring nostalgia for a childhood free from handheld screens and teenage years spent trolling the mall instead of each other. What Carrie finds interesting is the power of visual images, photography as formulaic bits of data, and the importance of acknowledging influence when it comes to media. And yet, within the power of photography, film, art, and music, Carrie finds an expressive power that is both terrible and beautiful—an experience felt in the body and understood within.

Do you think of yourself as an artist or a photographer?

I would say multimedia artist.

So neither?

Right. [Laughter] I was a photographer for a long time, and I still love it.

What is your multimedia work?

I use digital video, digital photography, sound, GIFs, any kind of media that you would find on a screen.

I saw your video installation at Boise State University in the Blue Galleries, it has a very specific aesthetic. Can we watch it on Vimeo?

Yes, just search my name. It’s called Folie à Deux. It’s a video I shot to be kind of hyperrealistic. It’s very well-lit, everything’s in focus.

The colors are super saturated. The textures all appear to be smooth, digitized.

Everything’s very symmetrical. It was very purposefully made that way, like a set, very designed. A lot of what I’m talking about is the artificial life we’ve created for ourselves in the 21st Century. So I want it to look like that.

There’s also a sense of playfulness, a sense of humor. It’s kind of quirky.

I would call it absurdist. An absurd look into modern life.

Your shirt is covered with lips. Is that absurdist? Or is it surreal?

Well, it’s uncanny, right?

The uncanny can be funny and creepy.

You recognize something from reality, but it’s a little off. I talked with Kate Walker (Associate Professor, Interdisciplinary Art at Boise State University) about the uncanny a lot when I was doing my graduate work. I wanted to create a feeling of familiarity [in the video], but the way people are behaving isn’t quite right; their affect isn’t right.

The people are eating tacos, but a very specific kind of taco, I think the Nacho Cheese Doritos® Locos Taco? [Laughter]

Yes, I’m interested in artificial food. I think chicken nuggets are interesting. To me that’s a symbol of the times we’re living in. And I also really love them, I like Taco Bell tacos. I don’t know much about chicken nuggets, but they seem like a good symbol of fast food to me.

In the gallery there were objects around the room, along with the video projections. I think I saw a Thighmaster.

Yes, pop culture fitness gadgets. I grew up in the 80s and 90s, and there was an obsession with fitness, even now, although it has changed. But symbolically, the people in the video are going through a routine, like a fitness routine.

It comes from your own experience?

I found myself, over the years, off and on, getting into different fitness trends. The obsession with being thin or being healthy, or whatever it is. It’s ridiculous, so I’m kind of making fun of myself.

I am a big fan of the body positive movement.

Right, I think a lot of the things that I’m commenting on are starting to change. There is a push back on digital life. People are becoming more conscious of how consumerism is affecting the planet. I think it’s a really good time to look back on the recent past, on rabid consumerism—it’s just a very strange time.

Do you have plans for your next project?

I do have an idea of what I want to do next, but it would require like a large space, and somebody willing to let me do whatever I want.

What do you want to do?

I’m really interested in the time period from 1996 to 2005, the period before Facebook, Myspace, before digital life was integrated with our lives. I’m interested in office culture and advertising from that period. It’s like a crossover period where analog lives became fully integrated with the digital world.

It kind of makes me sad.

A lot of people tell me that. A lot of people tell me when they watch my video they find it funny, but afterwards they feel sad. I want to do an installation with objects and things from that time period; I think it’s a really unique time.

What do you like better Facebook or Instagram?

Instagram is not as much of a sad swamp of negative feelings [as Facebook], you know. It’s image based. But I don’t naturally gravitate toward digital video or even digital photos [online].

You don’t sit around and scroll?

I don’t find it satisfying. Not in the same way as looking at material photographs.

So, no Facebook or Instagram?

No, neither. But I am interested in [social media] as part of photography now. I see myself using the medium to talk about our culture, which is saturated with digital imagery.

But why office culture? I wonder what’s drawing you to that. I watch things bubble up on Instagram and other media as a sort of collective unconscious and I’ve noticed an office aesthetic popping up.

I think I’m interested in office culture because when I got into photography in the 90s everything was still done in the darkroom. Part of the reason I chose photography was because I didn’t want a desk job. I wanted to be out doing things, making and creating.

Not sitting?

Right. And so as soon as I got out of college, everything went digital, so I ended up sitting in front of a computer for many, many years and being in an office for many, many years while things changed from analog to digital. I was observing the way images change, the way creating imagery changed. I had access to the internet all the time, so I was always online.

What were you looking at?

Everything.

But not on Instagram and on Facebook?

This was earlier. But there were blogs, and pop culture has always interested me.

Let’s talk about pop culture. What about it?

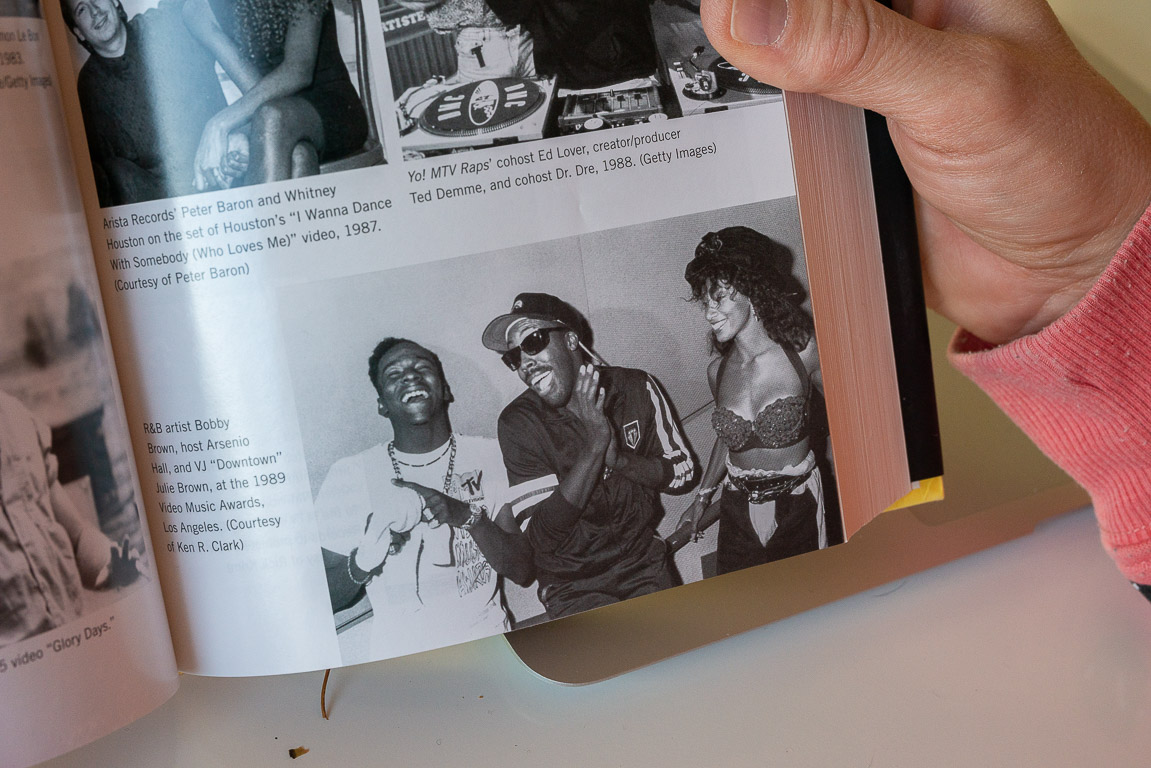

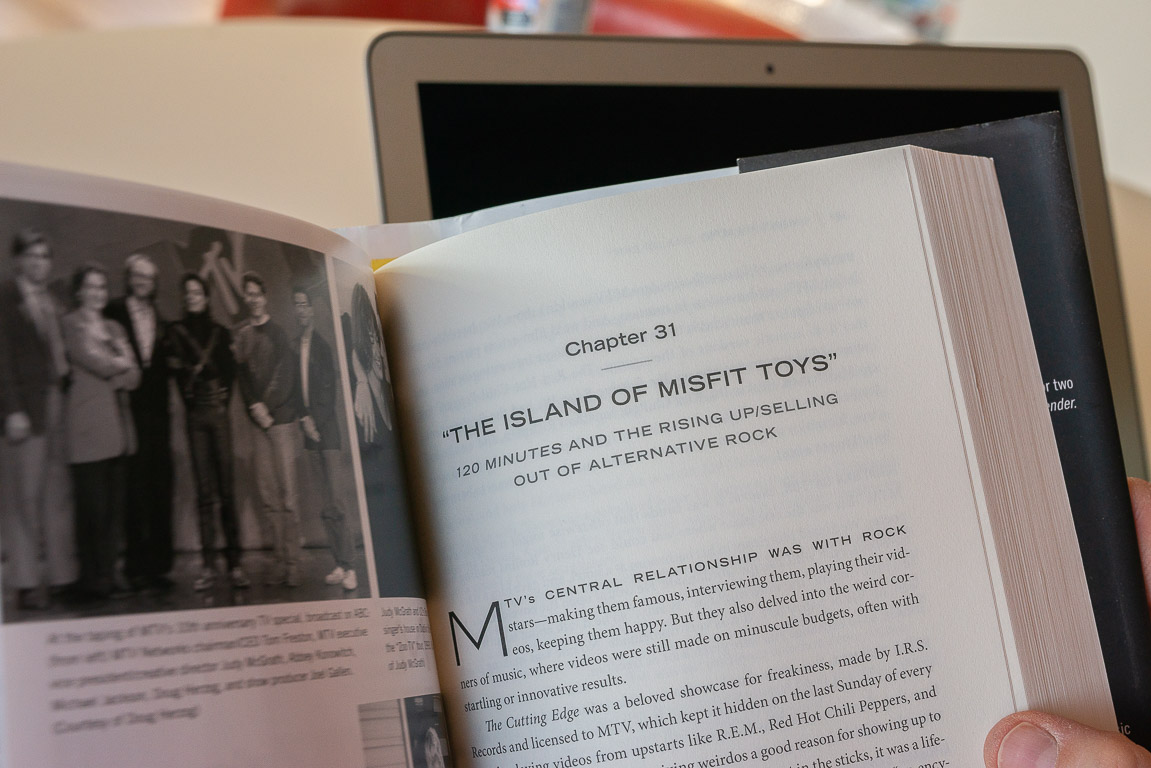

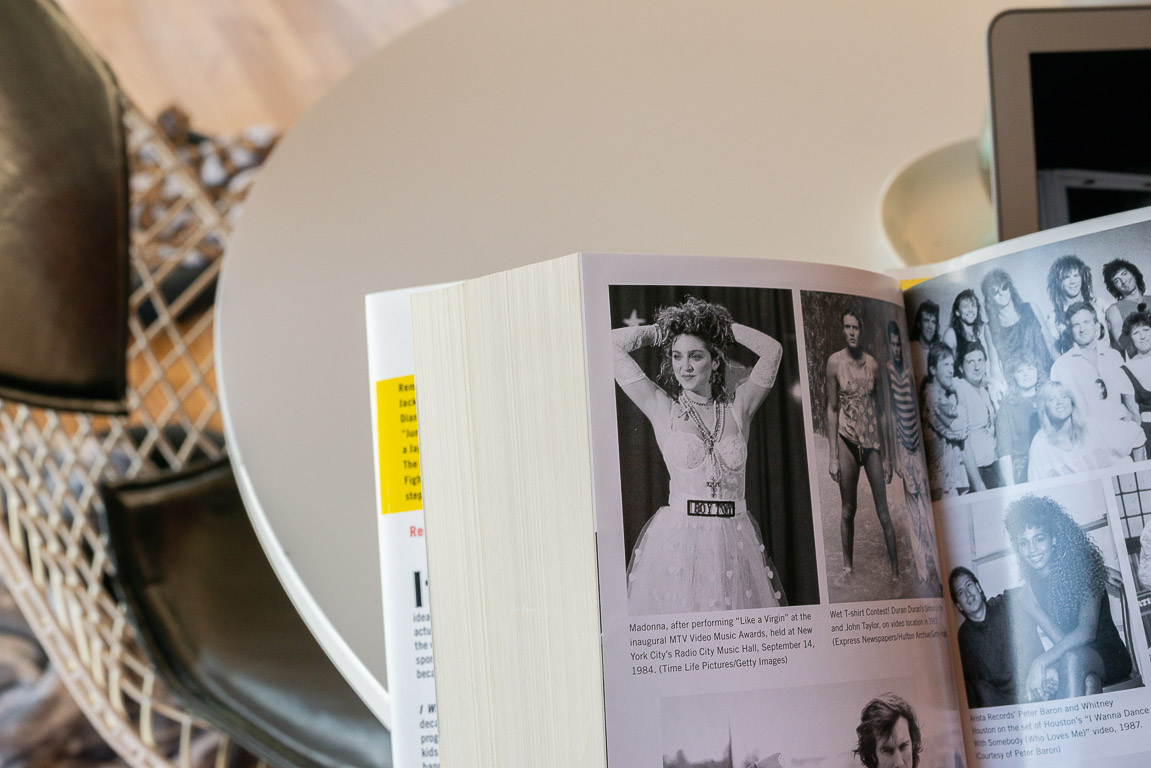

I grew up in front of the television, particularly MTV. Around first grade is when I remember watching MTV for the first time. One of the first videos I saw was “Home Sweet Home” by Mötley Crüe. It was very inappropriate for a six‑ or seven‑year‑old. But at that point I was totally hooked. My teenage years were basically [spent] watching MTV. And hanging out at the mall. I love malls.

We didn’t have cable TV. But I did go to the mall a lot. Boise Towne Square?

We didn’t have cable TV. But I did go to the mall a lot. Boise Towne Square?

I remember when it was built. Everybody went to check it out. It was farmland out there. There was nothing. Then all the restaurants popped up around it. Restaurants serving the kind of food that I’m interested in as an artist right now. It’s very nostalgic.

If you directed a music video, what would it be like?

There’s an artist I really like—Alex Da Corte. He collects a lot of thrift objects to make his installations. Things from pop culture, or, for instance, sub sandwiches. He did a music video for St. Vincent. They’re very staged. I think I would have a similar aesthetic.

After earning your BFA you went straight to commercial photography?

Yes, we were part of what was called “News Services” at Boise State. The university website was in its infancy. The university has transitioned to more of a business model, universities all over the place have done that. Along with it came a push to really market Boise State as—I guess I’ll just say it—as a product. We have the logo, an identity. The photography was in support of that vision.

How does an education in the fine arts compare to learning on the job?

In fine arts school, they’re pushing you conceptually. They’re trying to get you to build a body of work and to think in terms of cohesion. They don’t have as much time to get technical. For me, it took years to get good at photographing in any situation. I’d say that job really helped me, I traveled with the football team and documented fast‑action football, basketball, all those kinds of things, which I had no interest in as an artist, right? I learned a lot of technical skills and software.

Did you teach yourself?

We had help but a lot of it is just going out and learning on your own. Now, having taught photography courses myself, I think it’s harder to teach with digital cameras because [the students] get instant feedback. They look at the little screen, and think, “Oh, it’s a good photo.” They aren’t learning exposure, you know, the relationship between f‑stop, shutter speed, ISO.

Similar to how we can use the internet to find answers on the spot.

Right. They find out later that they didn’t take a very good photograph, after it’s downloaded. I think learning analog [first] makes you better. I tried to teach [students] what I would have wanted to know, right out of the gate.

What is a mistake you see photographers making a lot?

I don’t know if it’s a mistake, but this is why I don’t do as much straight photography anymore, because I see the same photographs over and over and over again. It’s gotten so formulaic.

What’s the formula?

You have different genres, right? Selfies, travel photography, all very similar, all very idealized. In the art world you see people pushing boundaries more.

Things that are going to surprise you? Or make you take a second look? Or show you something new?

Yes. I don’t see a lot of that in the masses of photography we consume. It’s so formulaic that we can consume it quickly. I don’t feel I have anything new to contribute. Why can’t I take a step out? Be critical of photography and still use the medium to talk about consumerist imagery.

It sounds like photography is dead?

It’s like a mass of data.

You were making work with pixelated images, the connection between the image and the ones and zeros it’s made of?

You are absolutely right. I’m trying to expose the building block of a digital image, which also actually distorts it. It’s kind of a metaphor for how imagery functions in our society. [For instance] can we really trust what we’re seeing in a photograph online?

Questions of authenticity?

Photography’s always had that baggage, right?

I think Laurie Blakeslee (local artist and professor) had the best quote ever, which is, “Photography is a lie.” It’s a paradox because it is both subjective and objective at the same time. The machine is objective, but the eye behind it is subjective.

I think if we don’t become better consumers of the digital world we’ve created, then we are going to continue to be suckers for people [who use images as a tool for manipulation]. Using imagery to [influence] us to buy things, vote for certain people. It’s important to understand how images act on you. How screens are changing your behavior.

And your opinions.

I’m not saying get rid of them. Just know what you’re doing, be conscious.

Know why you bought the scrunchie.

[Laughter] What?

VSCO girls, the hair scrunchie. It’s a thing.

I’ll have to look it up. If it’s a thing, I need to know about it.

What are some of your creative needs? You mentioned earlier you knew you didn’t want to sit at a desk.

I’m a bit of a vampire, and I need alone time, and I need time away from the screen. Even though I’m making work about it [laughter].

When do ideas come to you?

When I run, by myself. Then I have time to think, or sometimes when I go to sleep, which is unfortunate because I wake up a lot. My brain gets really hyper at nighttime.

If you could go back in time and give yourself advice, what would you say?

I would have liked to spend more time by myself, not beholden to anyone else. When I was younger, I was always in a relationship, or trying to be there for other people. It would have been beneficial say, “This is what I want to do, and I’m going to go do it on my own.” That would have helped in my development, helped me to be more confident. I think it would have helped my art. I would have made different choices if I would have not felt so obligated to other people.

It’s hard to know, though, huh? Is change a good thing or a hard thing for you?

I’m willing to make changes. I quit my job to go to art school. A lot of people were skeptical of that decision.

Would you take it back?

No, no. It was absolutely the right thing to do. Because I would have kept just working, and not made time for art.

I need structure, time, and support of the people around me to make artwork. What is your best art‑related memory?

It’s funny because school is so stressful, but I loved having the community of people in the studios in grad school.

Do you miss it?

I really miss it. Everyone was so different, but we had the same goals.

To get through the program?

Yes, and it’s a unique sort of person who is going to go that far with art, right?

In what way?

You have to take time out of work. People are focused on work, making money, but you have to leave that behind, you have to have art at the center of your life. It’s a special thing.

It doesn’t immediately pay back, that’s for sure.

No. You have to make art for the right reasons. You’re not doing it for the money.

If you were doing something else besides art, what would it be?

Forensic investigator.

What?

I’m obsessed with true crime. Very obsessed.

Ideally, you would work at night like a vampire, using your camera to solve crimes in the dark?

[Laughter] I would love that. I’m really into true crime podcasts.

What scares you?

I’m like an anxiety case study. One way of confronting your anxieties is to look at them, and try to understand them. That helps me feel better. Honestly, as far as true crime, I like podcasts better than the TV shows because I’m not viewing gory imagery. I don’t like to see horrible things.

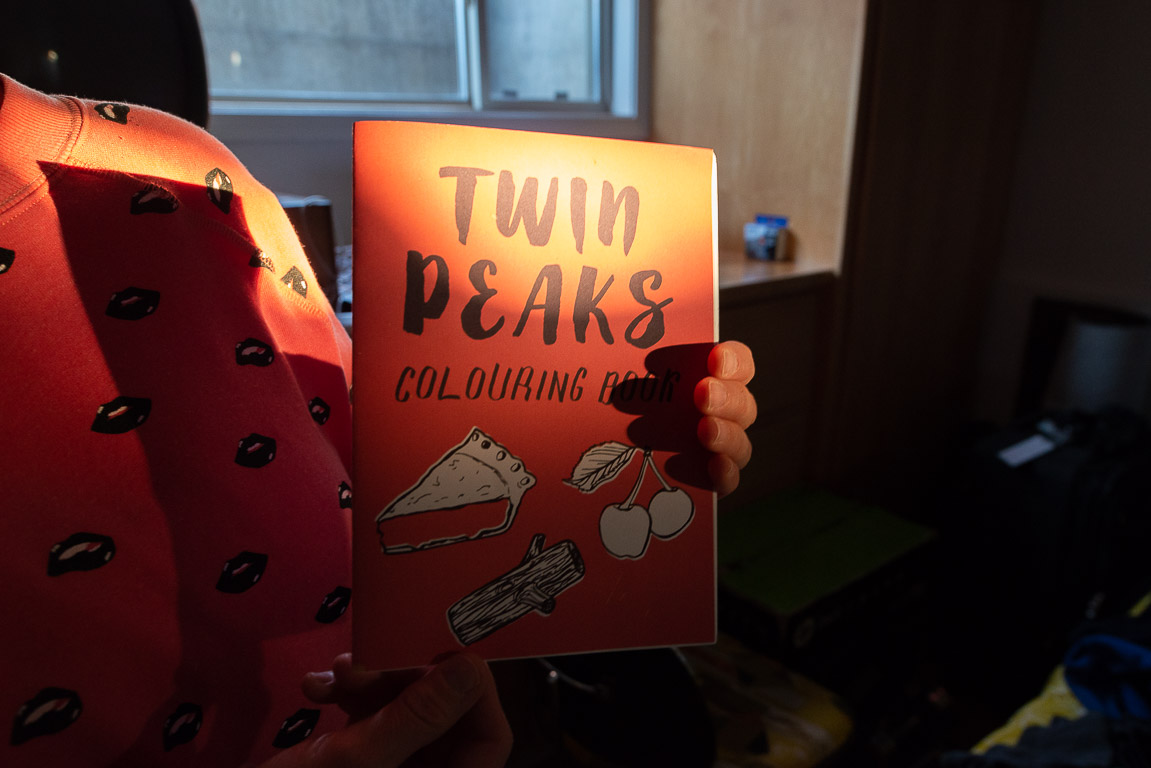

But you also love David Lynch.

True. I would say his work is disturbing, but it’s not overly gory.

His work is aesthetically pleasing and uncanny. That’s the thing.

He knows how to use light, he knows how to use—

Color.

He has a vision and a way of presenting imagery that’s disturbing and beautiful at the same time. There’s a song I’ve been listening to that I think is very beautiful, but I think if people might find it disturbing.

This is like your theme. It’s perfect.

[Laughter] It’s called “All Mirrors” by Angel Olsen. The video is really cool. To me, that has a lot of beauty in it. You know how music is, you can’t really describe it. It’s like art; sometimes you can’t describe the feeling it gives you. But it’s fleeting. When I’m with my daughter—you have kids … you know what I’m talking about—every once in a while you get that connection with them, and it’s awesome.

A sense of joy?

I would almost say it’s more like contentment, or when you’re experiencing something really beautiful. It’s not … it’s indescribable.

December 6, 2019

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History.