Creators, Makers, & Doers: Eric Follett

Posted on 4/2/20 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton ©Boise City Department of Arts & History

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton ©Boise City Department of Arts & History

Eric Follett is the current Resident at the James Castle House, where he is now following stay-at-home guidelines for COVID-19. We were lucky enough to interview him back on March 2 and to see his work up close. He will be staying onsite until further notice. You can track his residency on Instagram @jamescastlehouse.

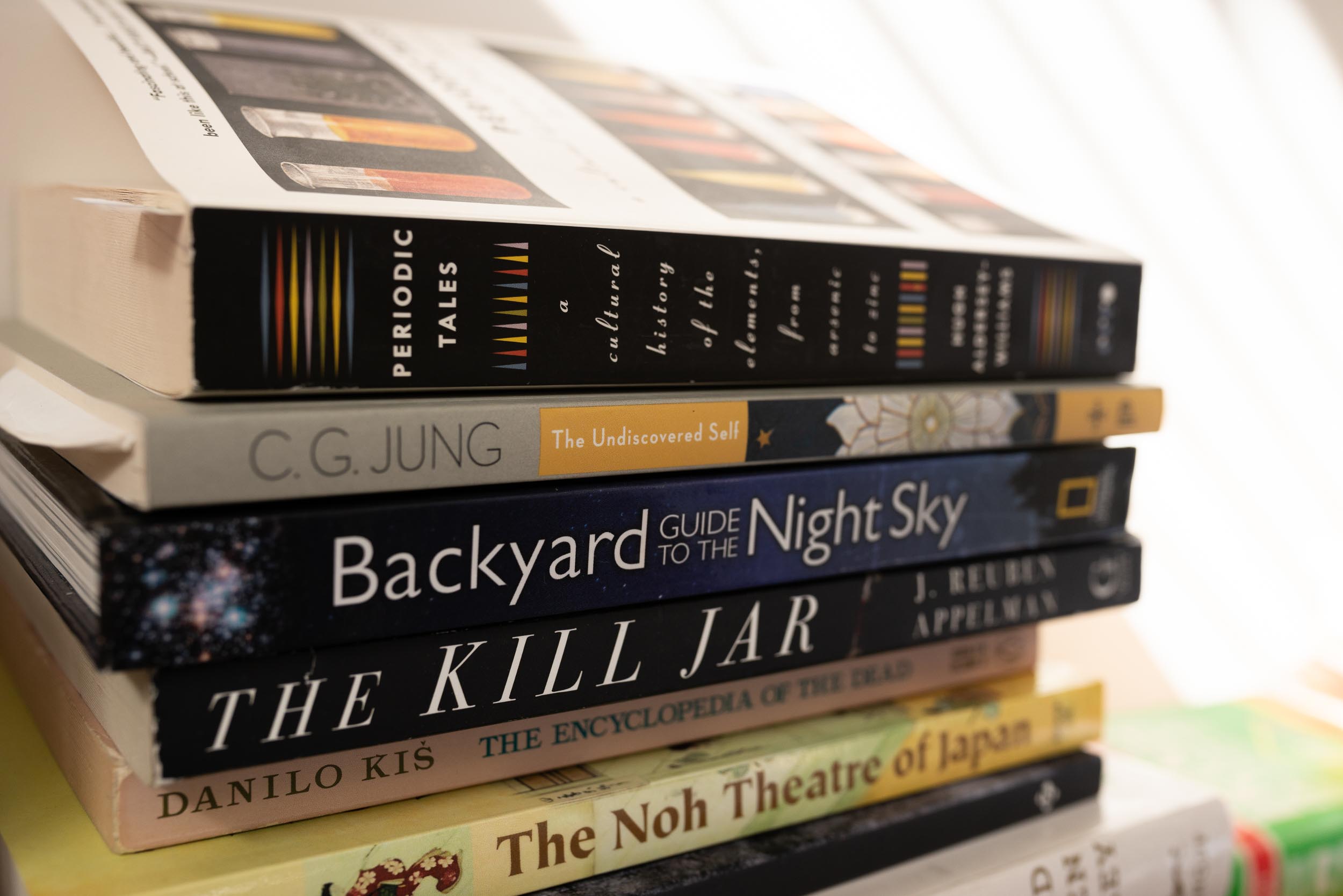

Eric is a writer and linguist who traveled from Idaho to Utah, Indiana, Nicaragua, and back west again, finding comfort in a landscape he took for granted. Mornings you can find him reading in the rocking chair, feeding a mind that has the capacity to think deeply across disciplines and history to tie works together by threads and themes of animacy, tragedy, and descriptive phrases like “a smudged character of things;” Eric’s work gives us an instant and lovely vision of both a literary passage and a work of art. Originally from Idaho Falls, Eric’s education took him to Purdue University, then into South America, where he worked with a community of Mayangna people to support in their effort to preserve the language. We talk about everything from driving a city bus in Bozeman, Montana, to the complexities of being a linguist in a postcolonial world, and whether or not we would visit the moon. (Would you?)

Did you do anything for leap year?

Did you do anything for leap year?

I was up in Garden Valley. Did some snowshoeing, sat by the river, and watched the ice.

We should talk about watching the ice. You earned a bachelors degree, then a master’s, then pursued a doctorate, but decided it wasn’t for you. You moved back west and started driving a city bus, which I would argue is not terribly different from watching ice. [Laughter]

Yeah, watching the flow of people. While I was in Indiana, at Purdue, I developed a real taste for movement. I started doing a lot of road trips around the Midwest and to New England. I leaned into that restlessness. Driving a bus was a way to move around a lot and to see movement; people getting on and off, and traffic all day.

It’s a little bit solitary, lends itself to introspective.

Yeah. In graduate school there’s a sense that you always should be working on your project. If you are relaxing or letting your mind wander, there’s guilt associated with that. Maybe that’s just my experience; but— I moved to Montana with the intention of writing and hiking. I was looking for a job that allowed me time to clock off and pursue my own projects.

A routine that allowed you time and energy for creativity?

A routine that allowed you time and energy for creativity?

Yes, I was looking to find a job, any old job, so I could write in the evenings and hike on the weekends. Bus driving actually turned out to be a superb mixture of both, because while I worked, my mind was free to wander, to develop stories and ideas. Also it allowed me to experience a segment of the population I wouldn’t have normally, and to be part of someone’s day.

Are you a people watcher? I can only imagine what that might do for a writer.

Yeah, I’ve got a story centered around a bus driver in Bozeman, Montana. [Laughter]

Narrative fiction?

Fiction is mostly what I do. I’ve been working on a short novel.

You found inspiration on the bus?

Driving a bus you experience little snippets of people’s lives.

Like what?

Oh, man, that’s a really—that should be an easier question to answer. Reality becomes blended with fiction when you’re drawing from anecdotes and building stories that way. Central to my memory was a woman from Philadelphia, or Queens, or something, I don’t remember. She had a thick metropolitan Eastern accent and loved to talk about the British royal family. She would sit behind me and talk about Prince Harry.

She liked to gossip about the princes? You probably didn’t get much of that at Purdue. [Laughter]

It was a bizarre experience for me. Also Bozeman in particular has a disproportionately high homeless population because they have good services. It’s a free bus service so a lot of [passengers] are members of the homeless community, or students. It’s an interesting mix; segments of society blended together for a couple of minutes every day.

You set up the perfect storm: people watching, a fixed route, and the weekends free to hike and think?

You get into a nice rhythm. But there’s variation inside that fixed pattern‑ like, James Castle and the idea of working with specific images, within specific parameters and finding variation inside what seems a narrow topic.

I need a lot of constraints to make art. Particularly so I can break them.

Yeah, I’m not an art historian, but artists like Mark Rothko or Piet Mondrian, limited themselves to very specific forms. The range of expression they achieved within those limits is pretty mind‑blowing, and counterintuitive. There’s something about giving yourself strict rules and examining what’s created within them.

What kind of parameters are we looking at with your work here, at the James Castle House?

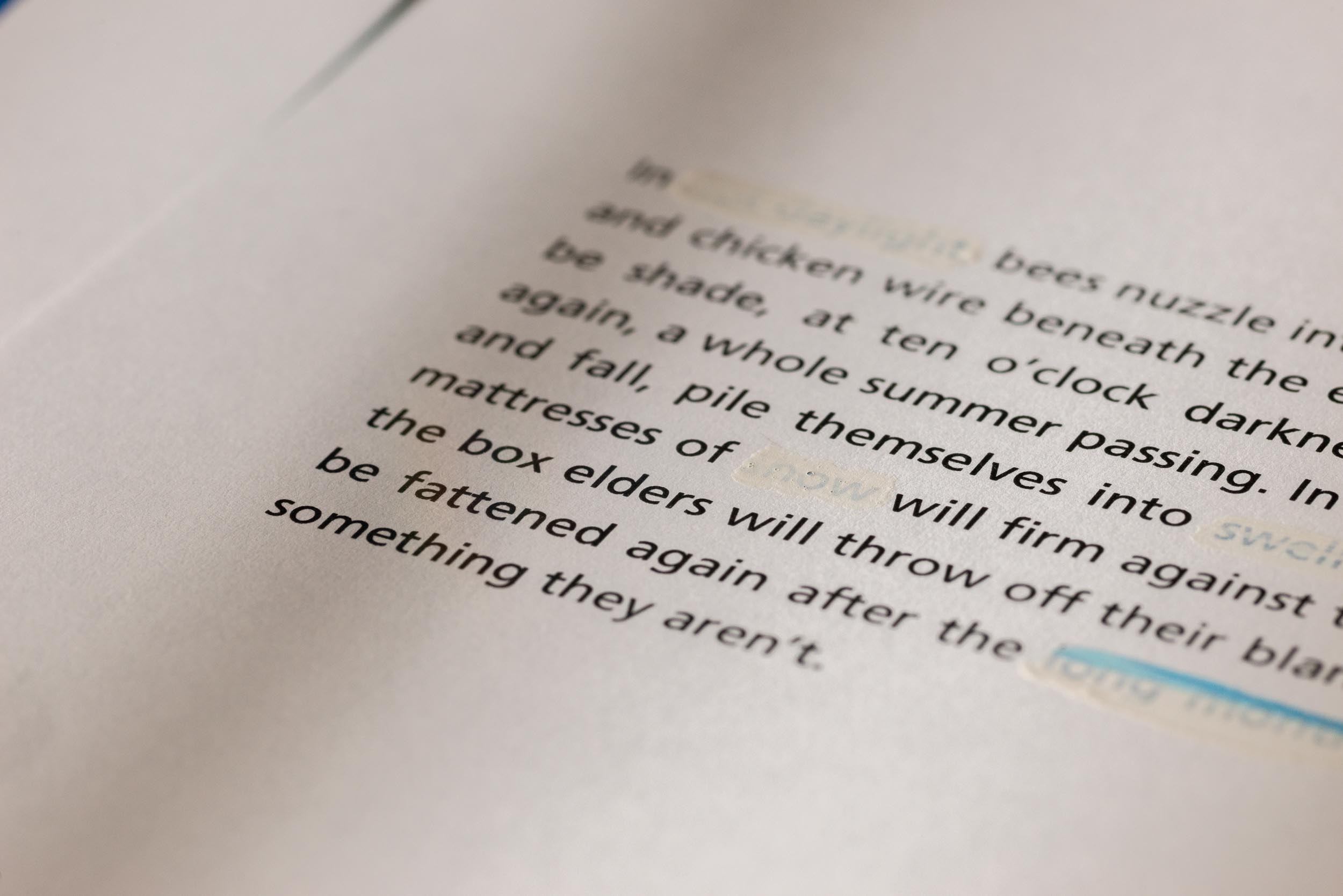

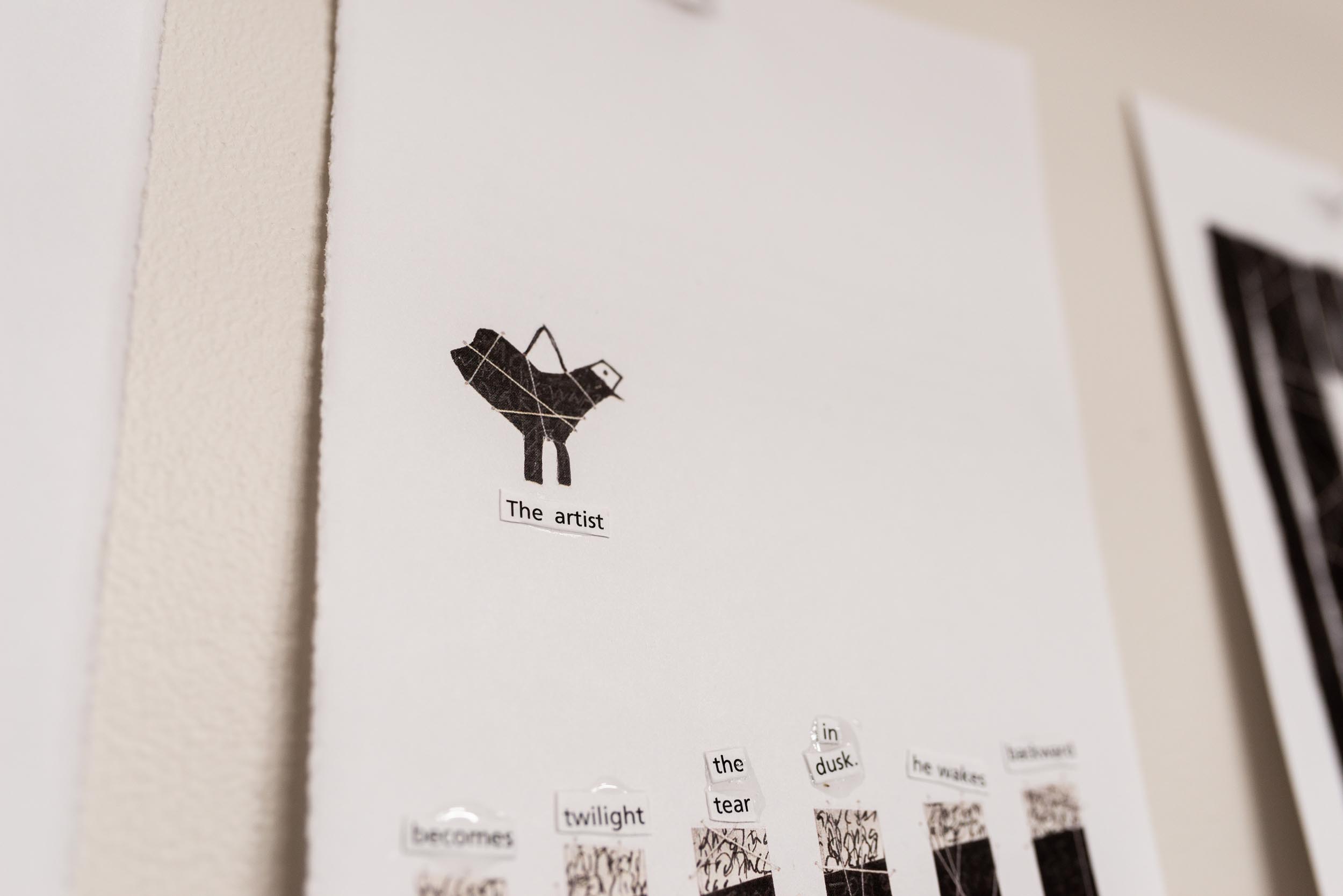

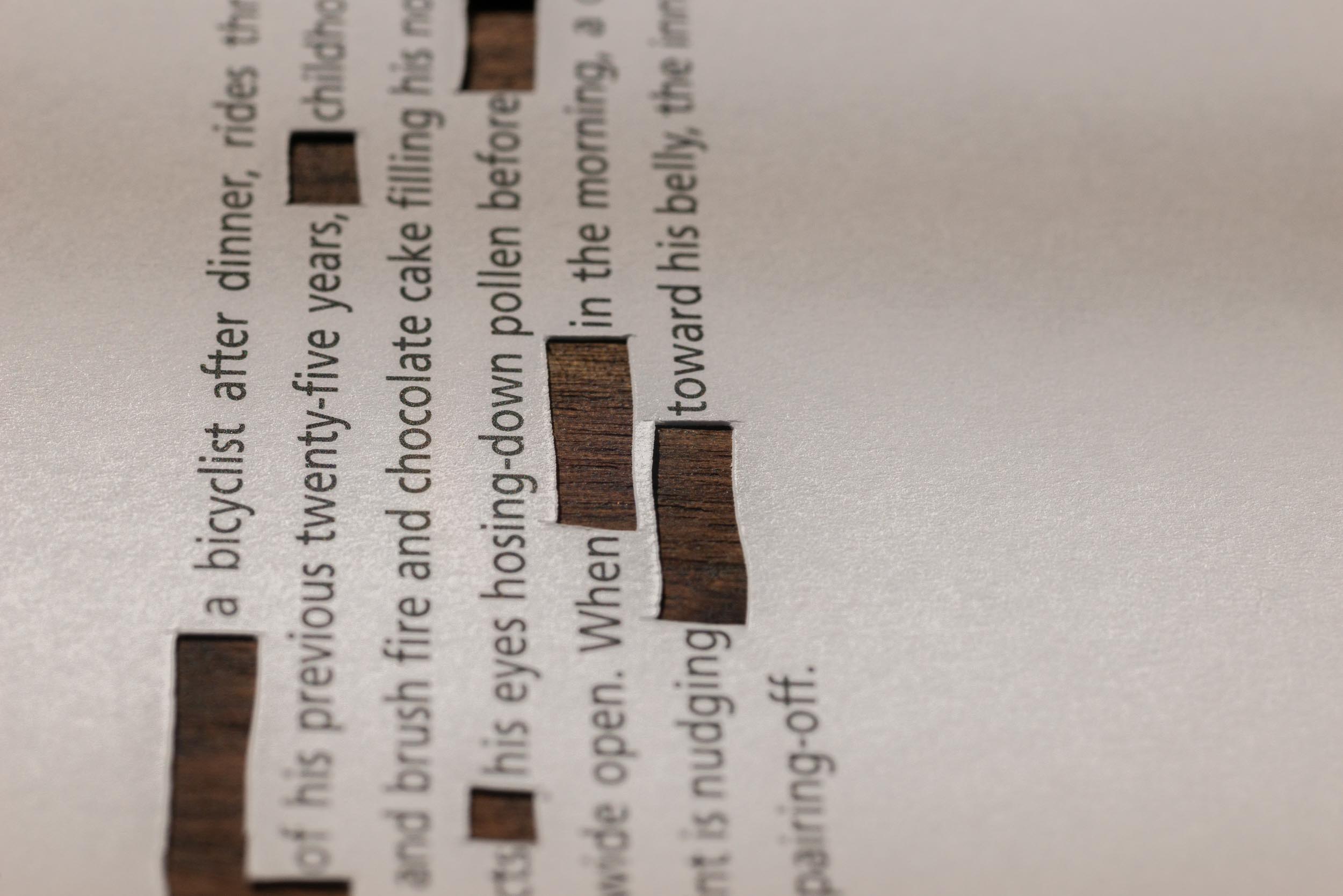

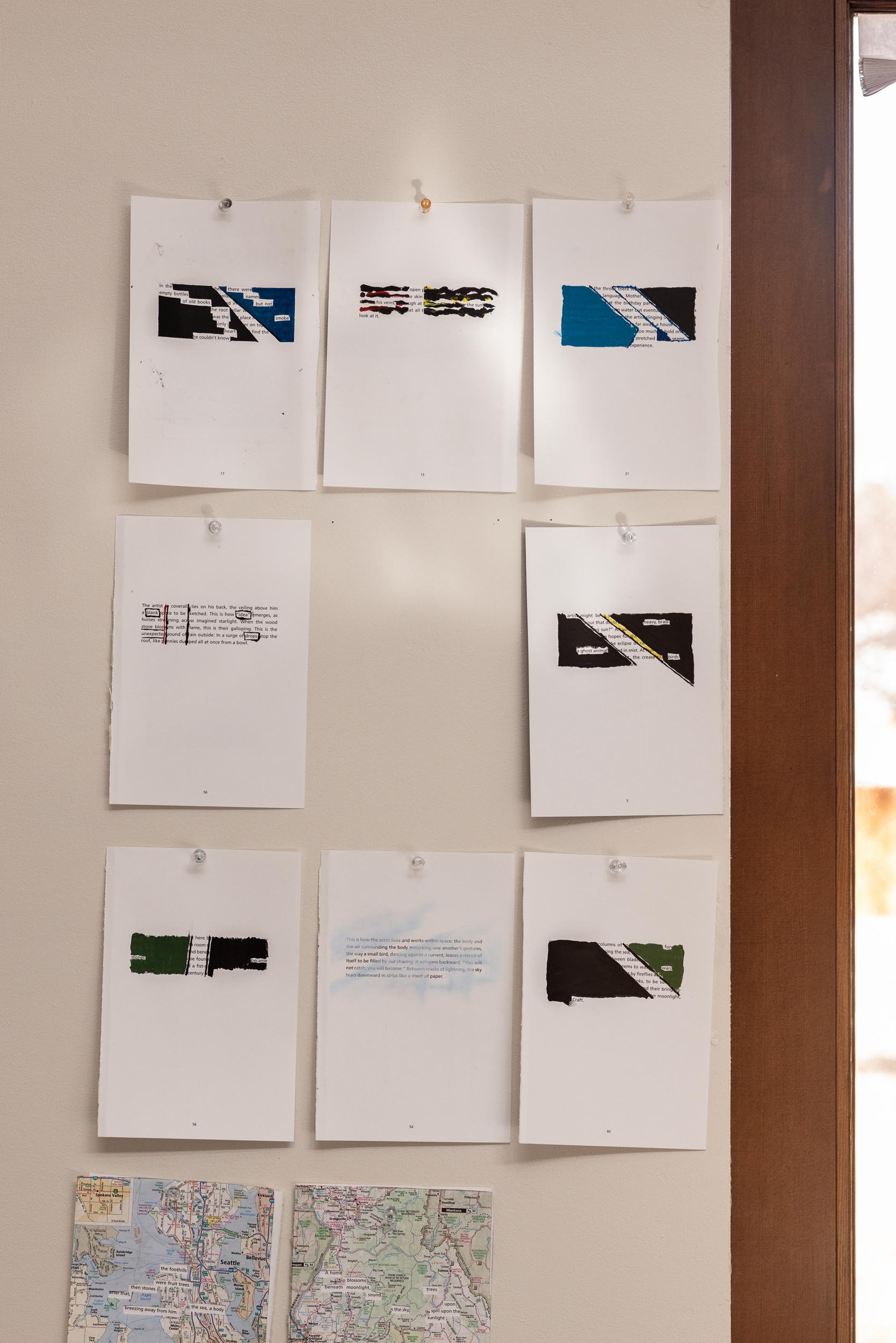

I hadn’t thought of my work in that specific way, but, yeah! These poetry series are all in groups of eight. I’m working with a very limited text, they are all pulled from Woodsmoke, by J. Reuben Appelman and Troy Passey.

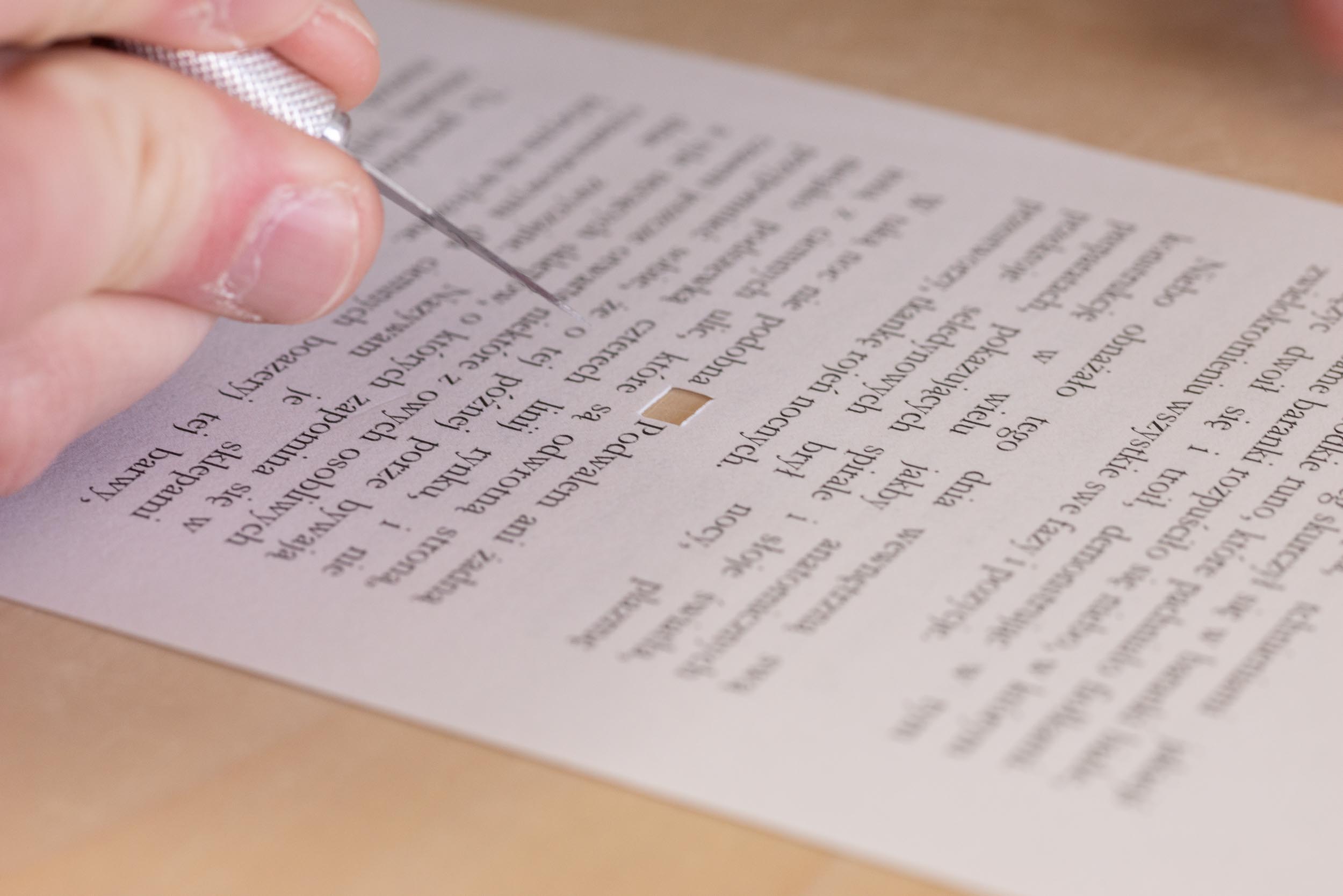

I see you are cutting up the book.

Each poem in that collection is very short and I am finding ways to pull out as many poems as I can from an already beautiful, short poem. In this case those are the specific parameters. I’m also working on haiku, which is another very limiting form.

You’ve inspired me to make a visual haiku. Thanks.

[Chuckle] That would be incredible. Haiku is one of those beautiful forms, that says a lot with very few syllables, but also points outside itself as it’s main device.

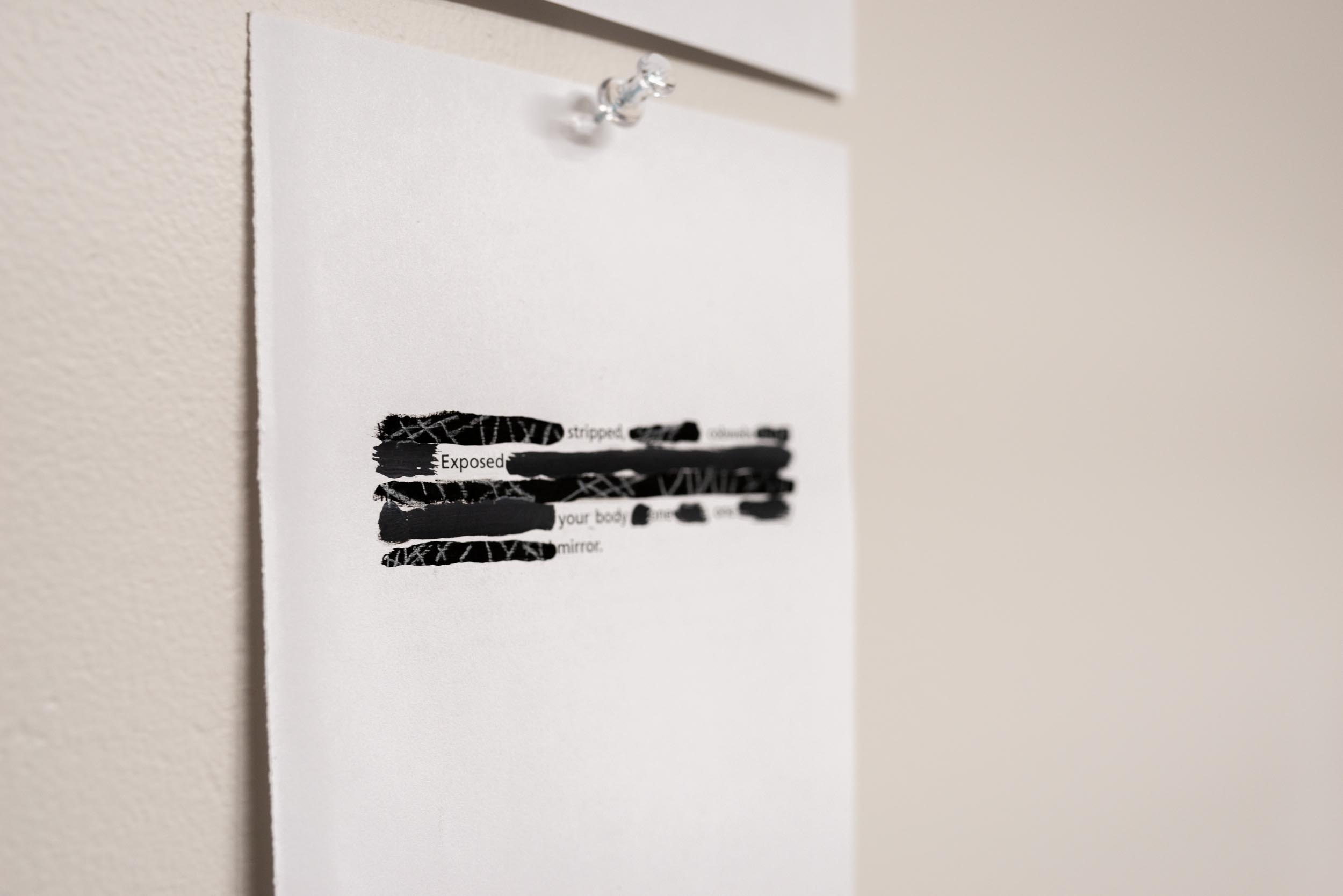

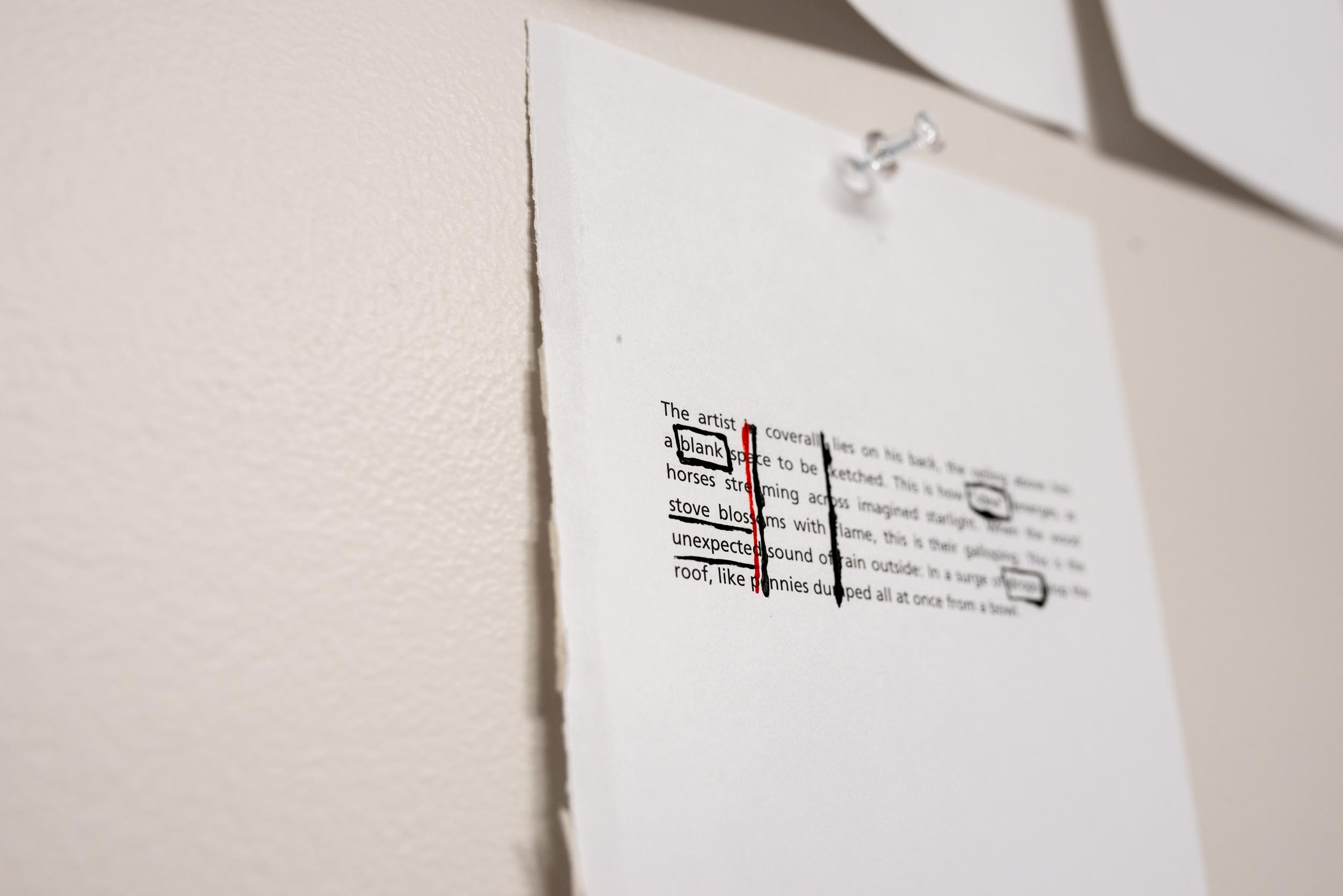

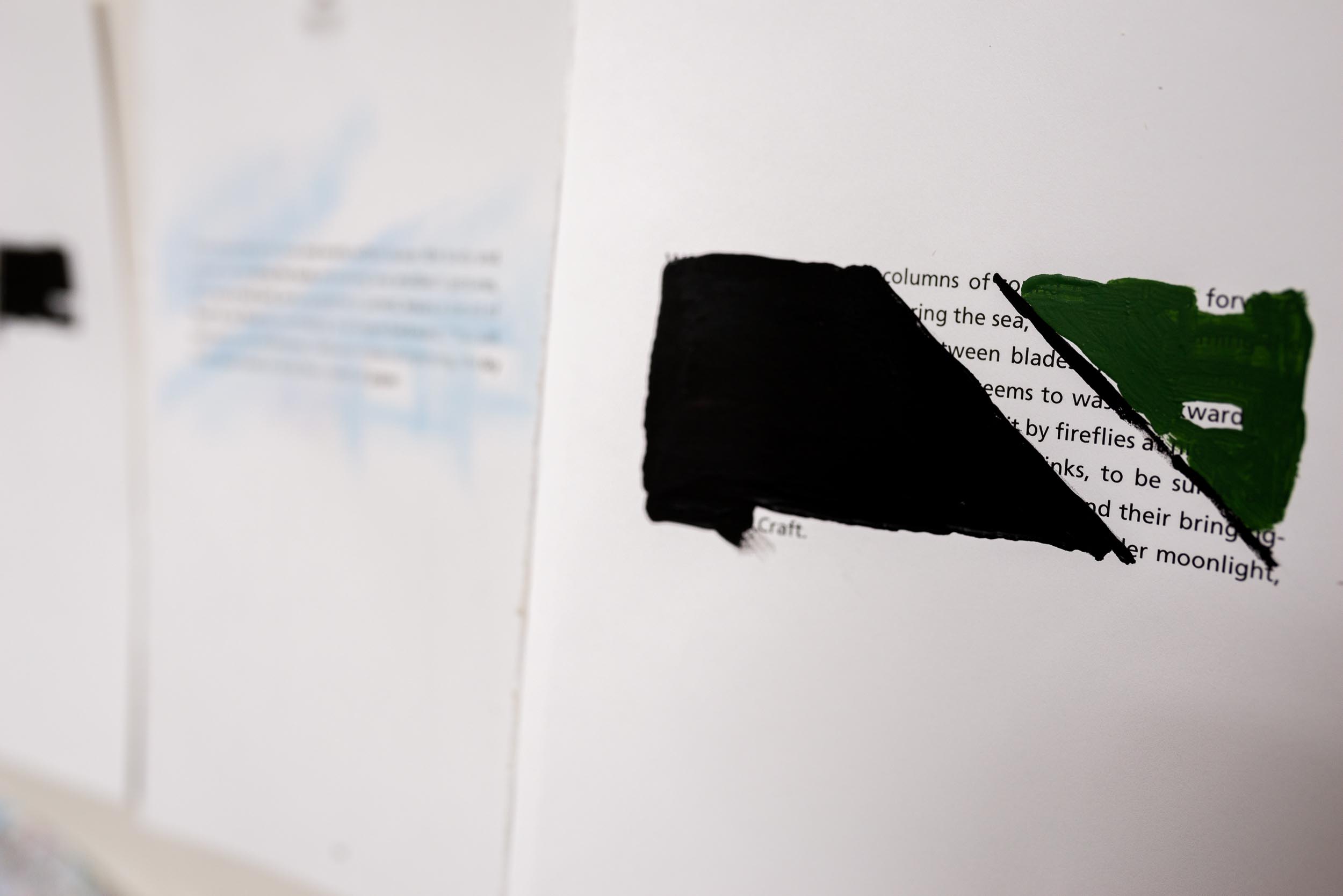

Looking at this work you used the term erasures. What is an erasure?

Erasure is a form of poetry. It’s also called blackout poetry. I was looking at something last night, I don’t remember the artist, but they did an erasure of the Constitution.

Taking an existing text and making new meaning?

Yeah, use a marker, black out certain parts of the text and leave other parts, pull a new poem out of an existing text.

You are also layering paint. You’ve got positive and negative shapes, a color scheme.

I have arrays of eight erasures, and each array shares a visual theme.

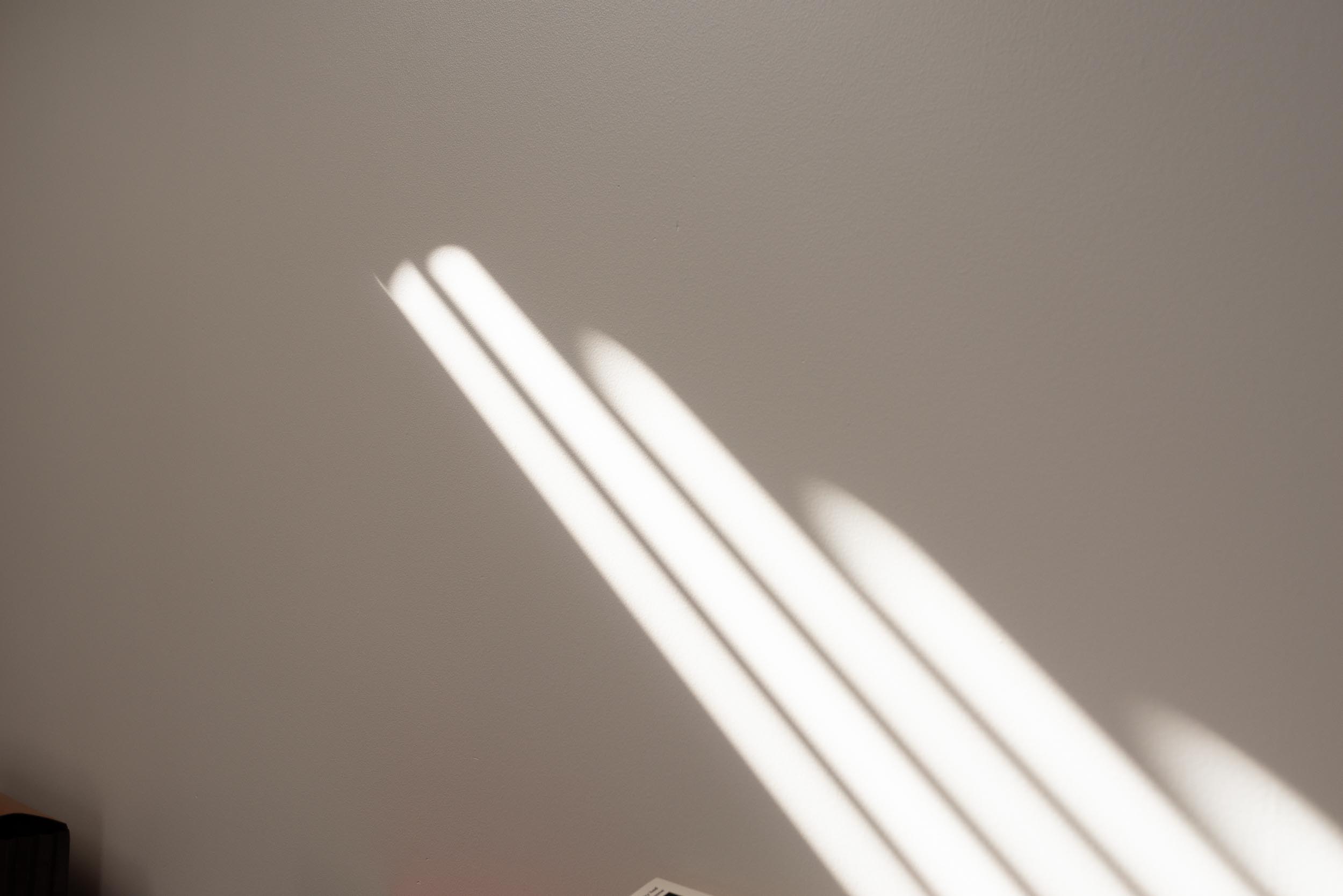

I see diagonals here.

Maybe thinking about like a shaft of light—

Kind of like the light that comes through this window.

Right. When I sit in the rocking chair and read, there’s a shaft of light that often falls across the page.

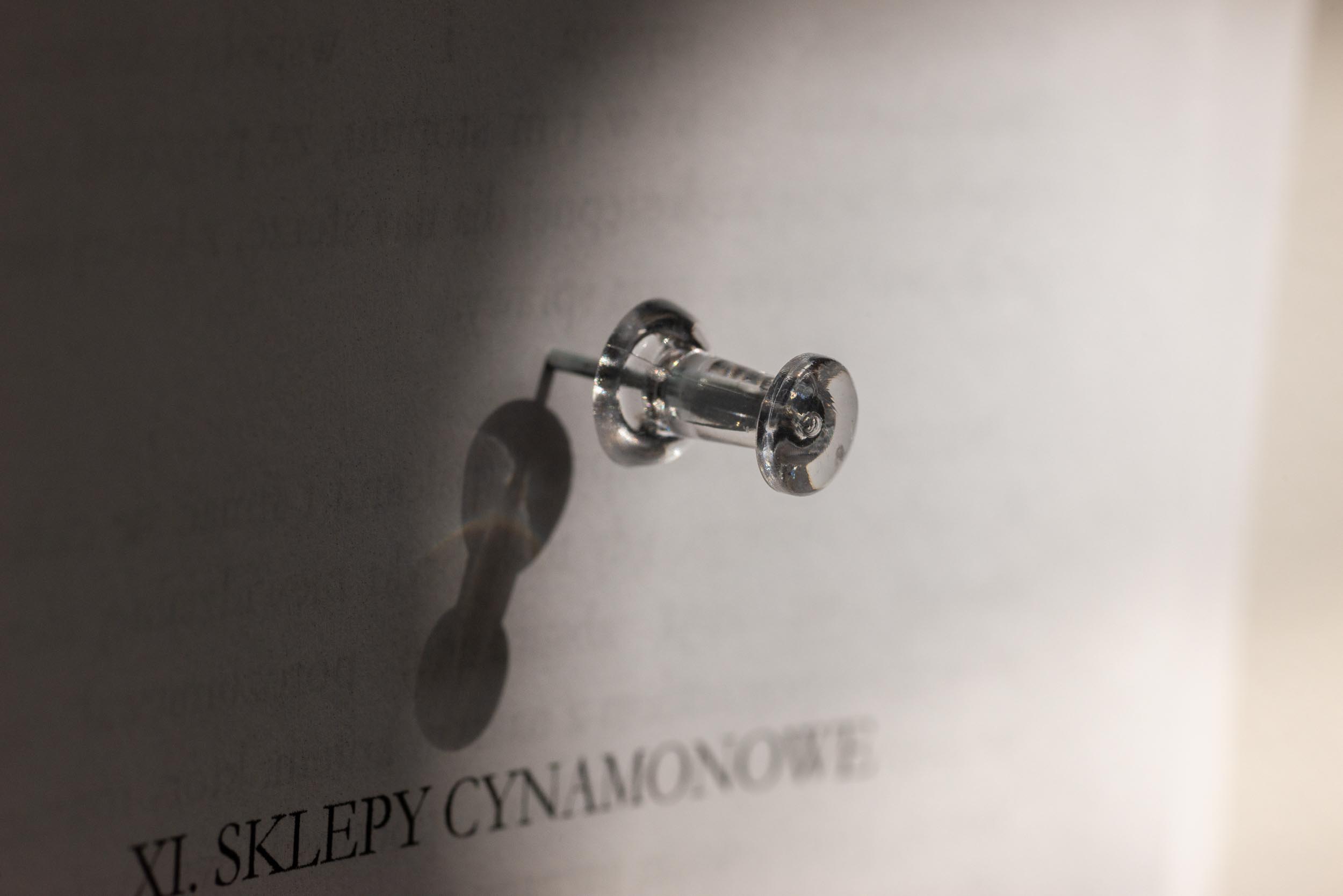

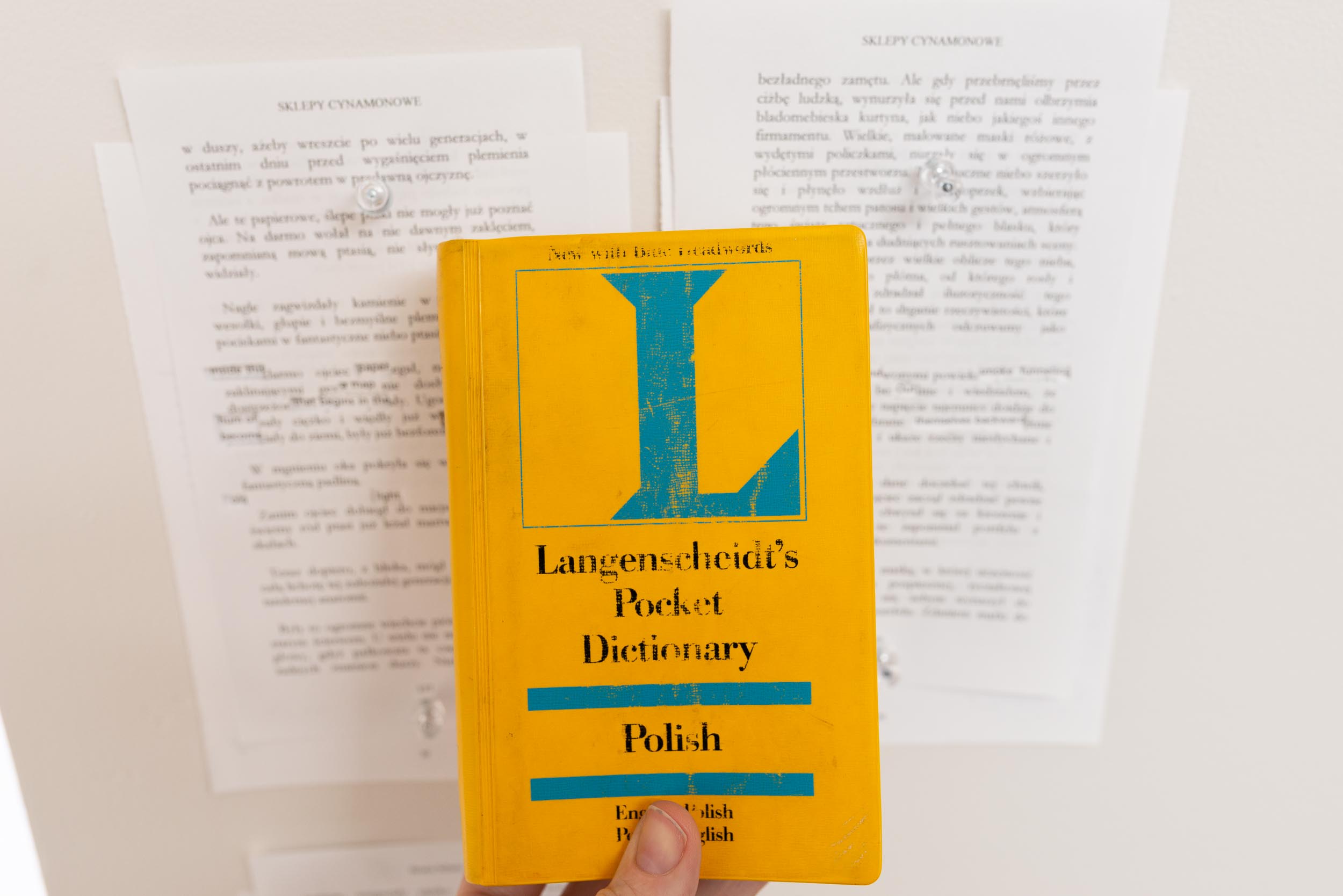

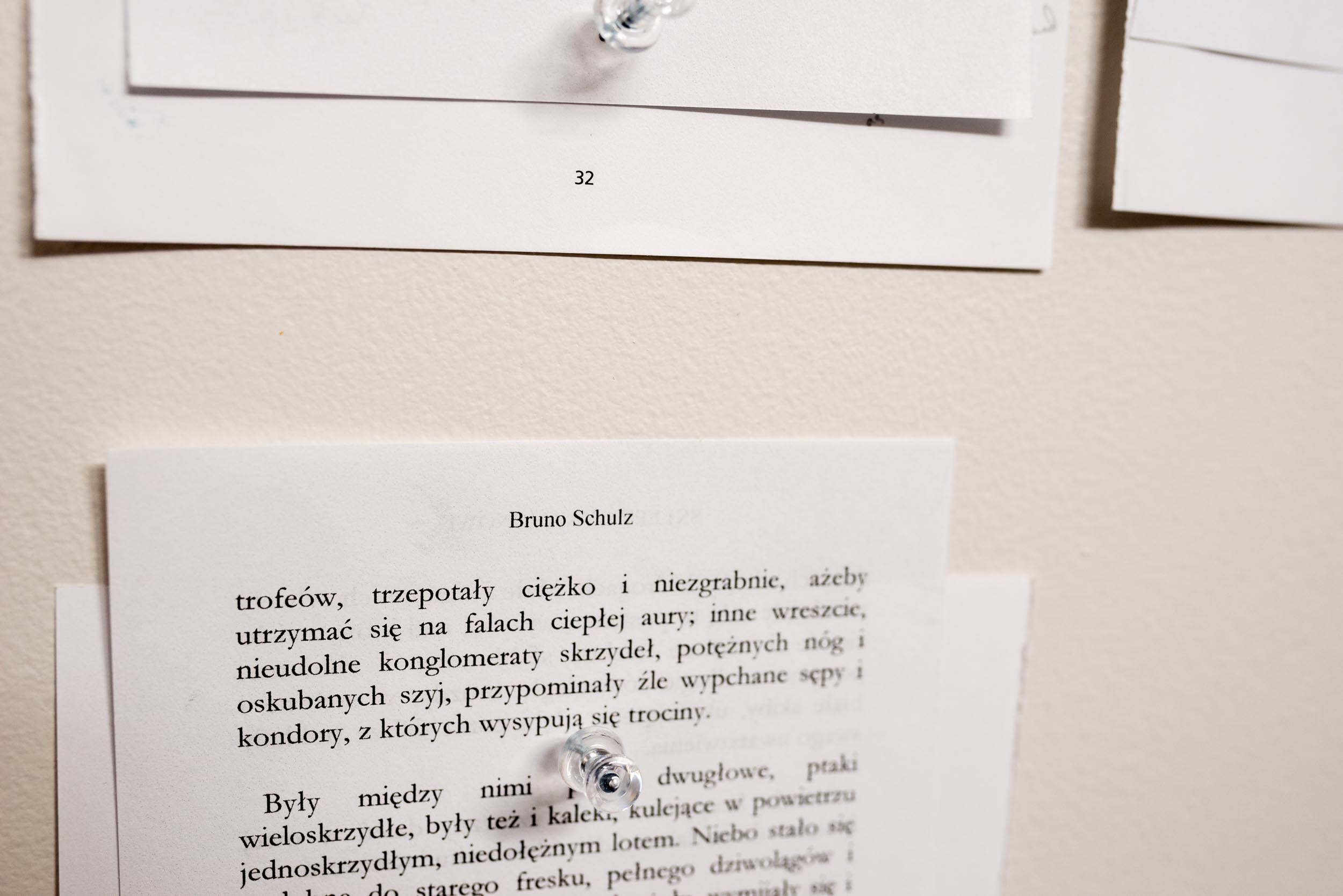

What other sources are you pulling from, is it Bruno Schulz?

What other sources are you pulling from, is it Bruno Schulz?

Bruno Schulz was a Polish writer. He was actually born in a small town that is now a part of Ukraine. He was a Polish Jew, a writer and a visual artist. He has a tragic story, he was shot dead in the streets under Nazi occupation in his hometown, Drohobych. He had only two collections published and an unfinished novel, Messiah, that was supposedly very advanced, but the text was lost. His career was cut short. I discovered his work in a story collection called Street of Crocodiles.

But it’s written in Polish?

I read the translation. The collection is in a loose novella form. It’s based around childhood and experiences with objects, and time. There’s a kind of a deep animacy, or, aliveness in the streets, in the shadows and in the objects; you know, daily encounters.

Things that normally are not animate, he brings to life?

Infused with consciousness. I really loved it, but was also afraid of it.

Why?

It’s very beautiful writing and I had a strong emotional reaction to it. That’s never happened to me before.

You said you had intentionally put the book away for a while, kept your distance?

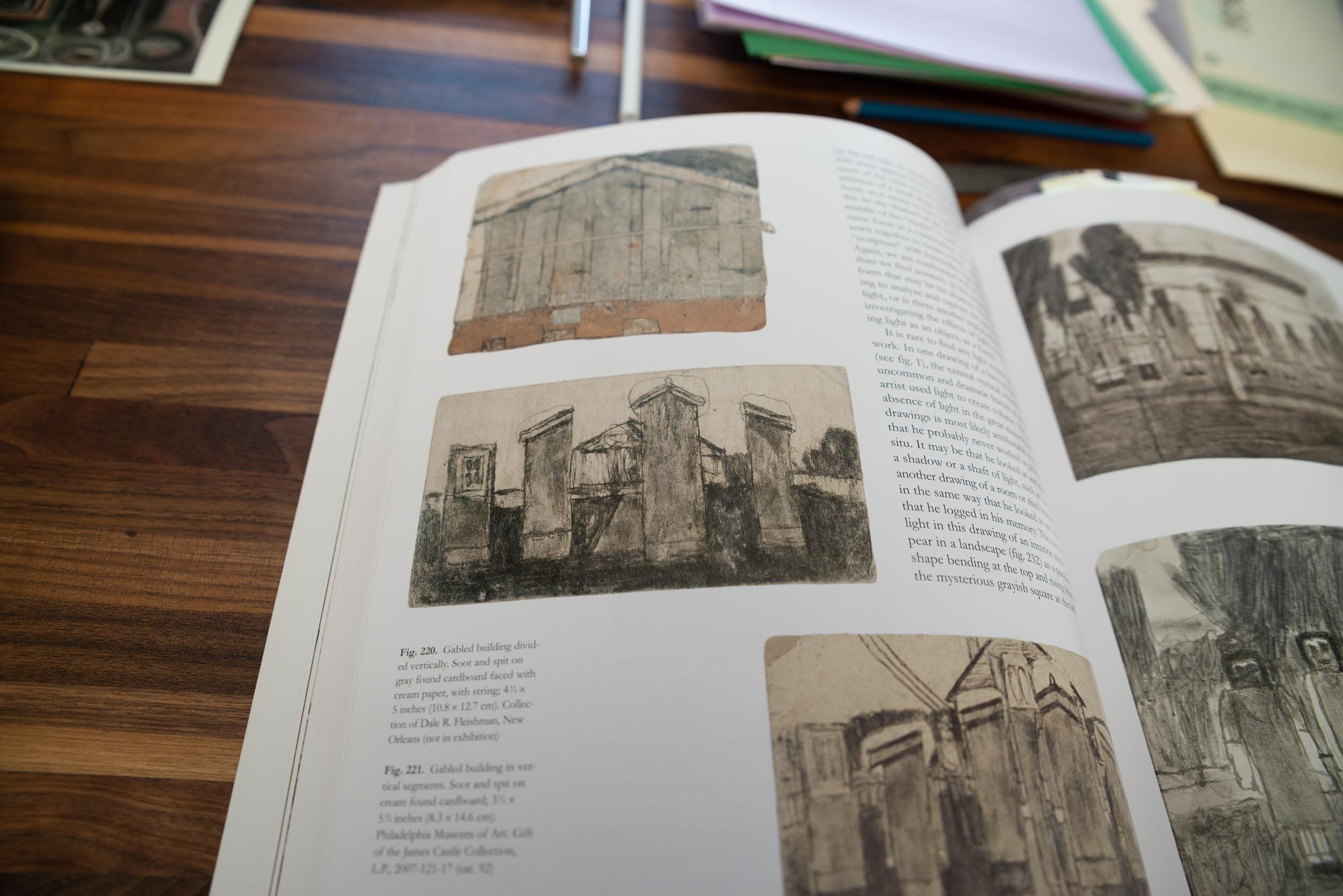

Yes, I didn’t read it again until I discovered James Castle. There’s some specific [similarities] between the two; the charcoal and the grayness, the smudged character of things. James Castle imbued his landscapes with attributes of living things, morphed architecture into human-like forms.

I totally see that. Street of Crocodiles is on my reading list now.

It seems almost scary, the way both James Castle and Bruno Schulz experienced an undercurrent of life beneath the objects.

That’s the parallel you are drawing, and it’s beautiful.

I haven’t explored it a great deal yet, but James Castle woke me up to Bruno Schulz again. These two men each produced a body of work that speaks for itself and transcends their biographical details.

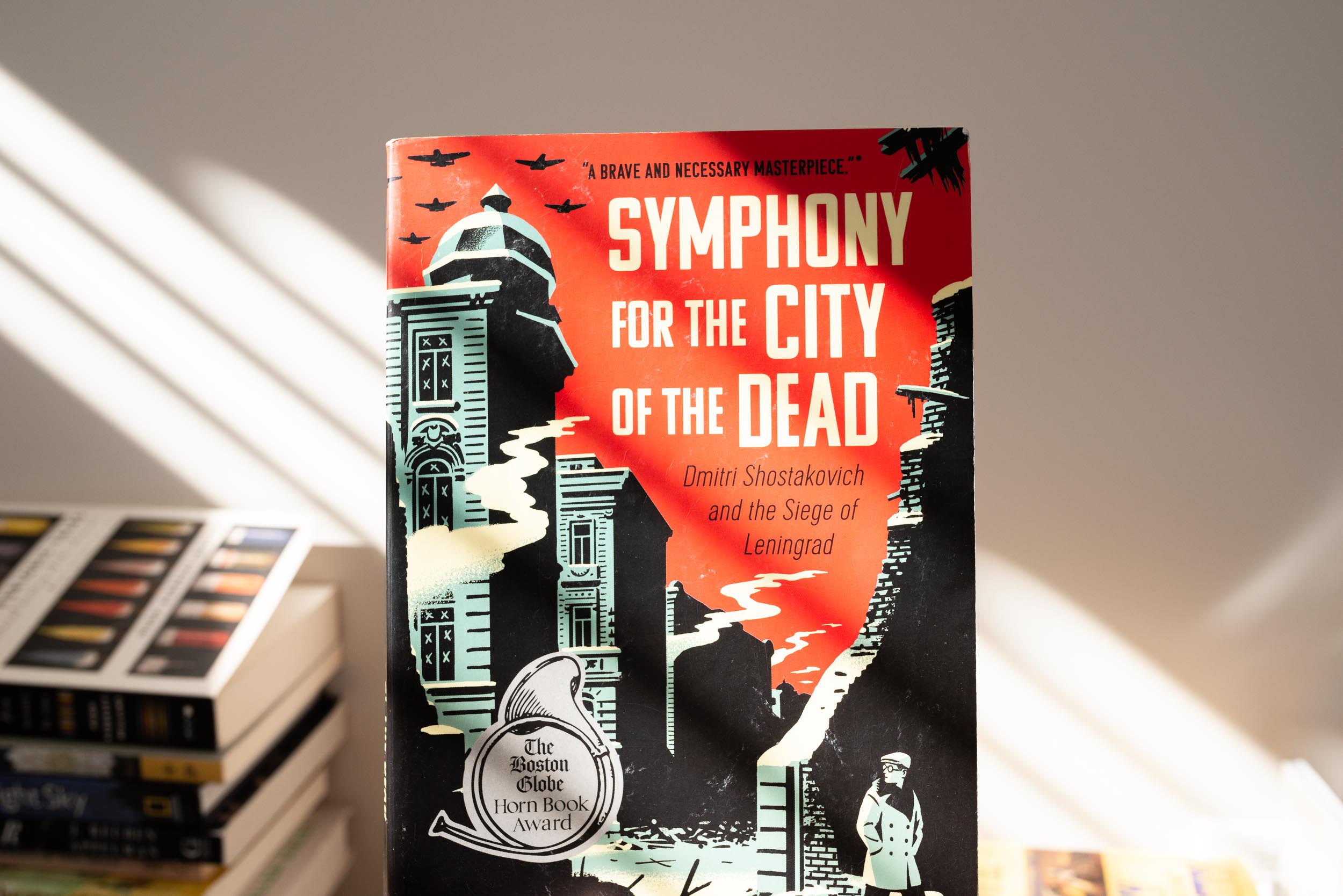

You also mentioned a composer?

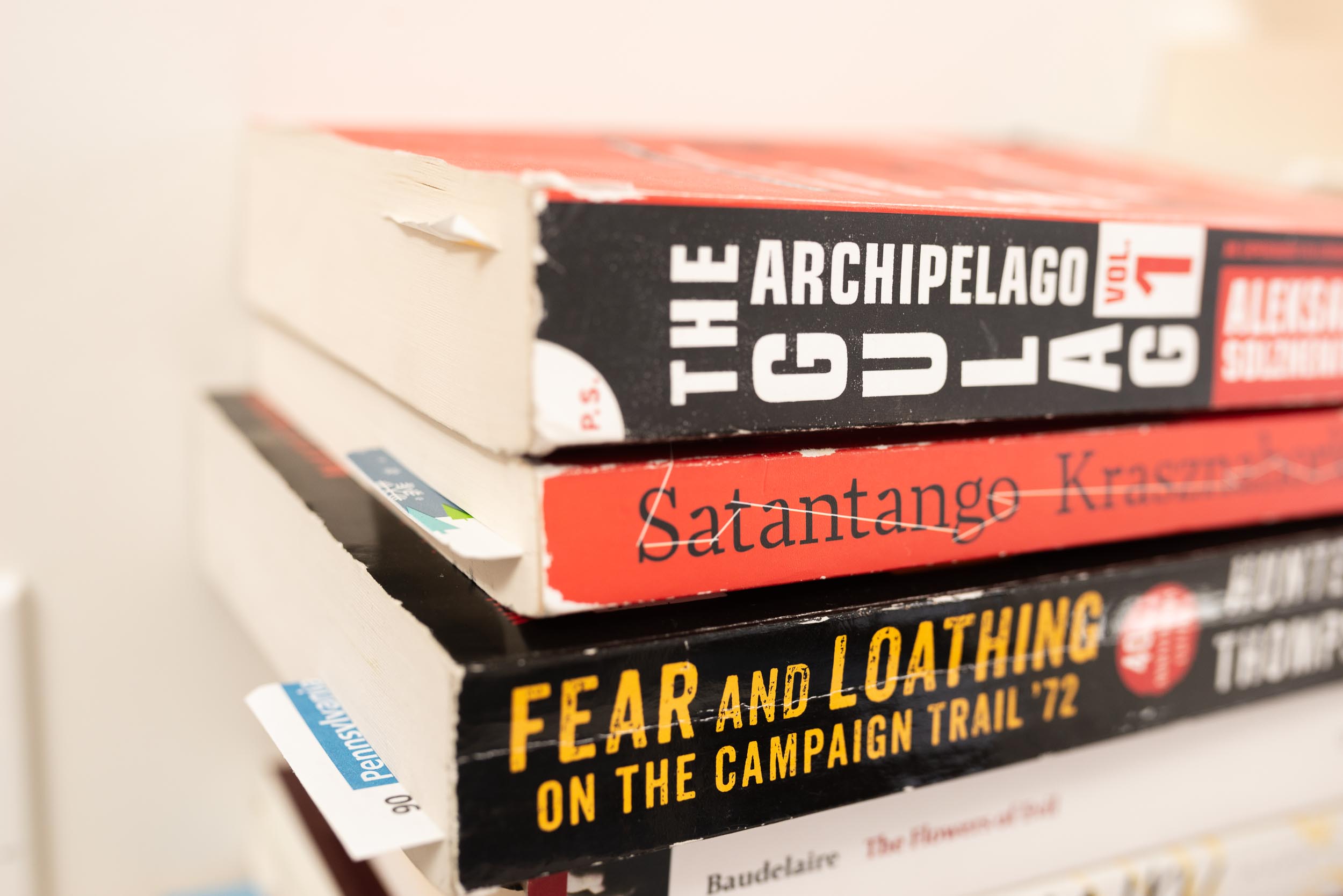

The Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich, he’s the third piece of this pie, the other artist who’s work holds emotional resonance for me. He was composing in Stalin’s Soviet Union, in the time of Gulag Archipelago. He ran afoul with Stalin after one of his operas, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. He lived with certainty that he was going be arrested any day and disappear into a Gulag. There are stories that he slept in the hallway of his apartment so when they came for him, it wouldn’t wake his family when they took him away.

Wow.

And, that he went about his day with a suitcase full of clothes, with the expectation that he would be arrested. On top of that he produced an incredible body of music.

What’s the Gulag?

The Gulag was the prison system, sort of a concentration camp system. Especially under Stalin and Lenin. It’s where political prisoners and, quote/unquote, enemies of the state were sent. His is a very tragic, sad story. But, again, the body of work Shostakovich produced speaks for itself and transcends his biography.

Were you listening to classical music while driving the bus?

Were you listening to classical music while driving the bus?

Yes. I don’t think I have a natural sensibility for classical music but I started listening to this program while driving my morning route; there was always a little story or nugget about the piece, or about the composer. The more I learned about the music, the more I liked it. I ended up responding emotionally to Shostakovich.

Did you have a sensation in your body? In your stomach, or your heart or your head or your—

I don’t know. That’s a good question.

Your throat?

Yeah, maybe like when you’re about to throw up. A feeling in your neck that builds to the back of your throat.

And then there’s an expansion.

[Chuckle] Maybe something like that. Maybe it’s just a metaphor; I don’t know.

We’re exploring new territory here.

It was the same with Bruno Schulz and James Castle.

Which work of Castle’s strike you?

One with a house that’s been sort of cut into strips, destroying the opacity of the house and showing the landscape through. Some totem drawings.

I’m going to change topics on you. Your masters in in biolinguisitcs, can you explain what that is?

[Laughter] Oh, boy.

I’ll try to keep up.

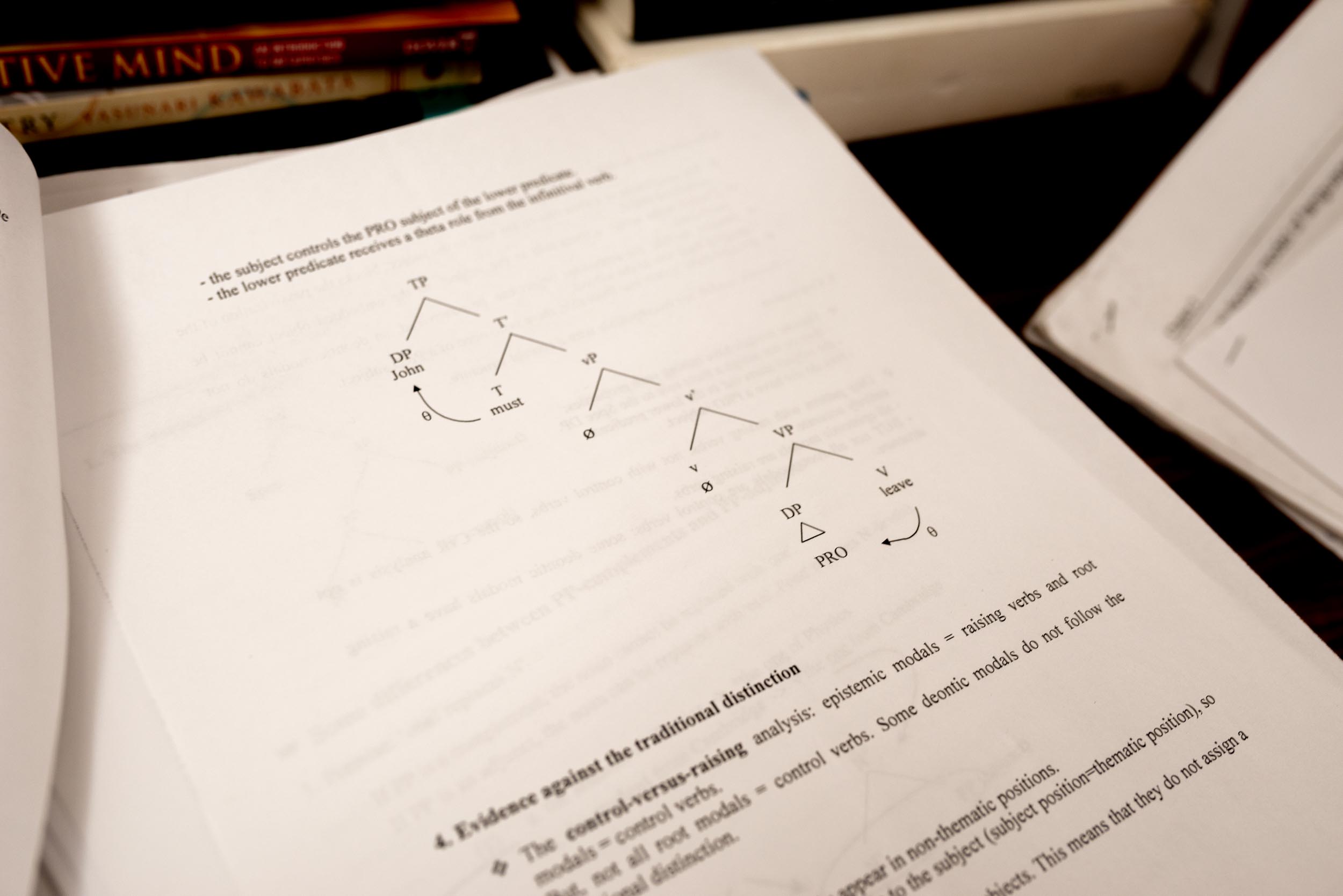

Right, poetry is only one part of the work I’m doing here. Another part is looking at James Castle from a linguistic perspective. I studied generative grammar, the generative enterprise. It all stems from the work of Noam Chomsky, who, in the 1950s, building off the work of previous linguists and philosophers of language, began to study language systematically, from a scientific perspective.

You showed me this diagram.

His work made kind of a massive Copernican Shift away from looking at language as a system of symbols used for communication and towards looking at language as an attribute of the human species. Rather than looking at what words mean or how we use them, he looked at the constraints on the system; at the computational system we use to put language together.

Hang on just a second. The computational system, the constraints. I kept expecting you to say culture.

No, culture doesn’t come into it.

So where are we, then?

A big part of the methodology he developed was building a hypothesis and setting up examples to determine grammatical versus ungrammatical sentences. That’a important because it’s not arbitrary. That’s the point he was trying to study; a huge body of data has come out showing there’s actually a very narrow range of language structures. Even languages that seem very, very different from each other obey similar constraints.

And the question we need to ask ourselves, is “Why?”

And the question is why, right. The idea is that there must be some biological inheritance, some cognitive system that we share as humans. No matter how different the language seems, at some abstract level they are the same. But, a system as complex as language that uses a limited number of purely symbolic units can create an infinity of expressions. Every day people say sentences that have never been said before.

We’re doing it right now, then. I can see why James Castle is of special interest to you.

James Castle is a really interesting case. I should preface this, when I experienced his art for that first time, it felt like language to me. I had studied quite a number of languages and linguistics in general, and his art kind of had—had whatever it is—

A familiar structure or— ?

I don’t even know specifically enough to say why, but that’s just what it felt like. That’s what I bring to bear on his artwork. That’s an idea I’m exploring. Not in a scientific, or conclusive way; I’m not making any claims about James Castle or about his artwork.

No, but it is interesting. Maybe we should approach his work like a code.

It’s compelling to think about his work as an expression of his linguistic capacity. If you look at language as a system of symbols, then someone like James Castle, who never acquired, or learned a language, would essentially be shut off from language. But if you look at language as a property of individuals, sort of a property of the brain, the fact that he didn’t acquire language says nothing about his capacity for language.

What kind of work might a linguist do?

My PhD advisor was involved with a community on the Caribbean side of Nicaragua, a group of people called the Mayangna. She was doing linguistics studies and language revitalization programs. I was able to go down multiple times and work with her.

So there’s a very small population speaking the language there?

A small population and also a very vulnerable population in socioeconomic terms. These are the kind of languages dying out at an unbelievable rate. I think it’s projected that the world will lose half of its linguistic diversity in the next 20 or 30 years. That’s something like 3,000 languages becoming extinct. With those languages we lose complex systems of knowledge; stories and myth, and relationships of people to specific landscapes. It’s a tragic outcome that is more or less inevitable due to things like globalization and neoliberalism.

So you work to save languages?

Kind of. There’s a group of indigenous linguists who my advisor had been working with since the mid‑’90s, training them as linguists to study their own language. You know, anthropologists and linguists have a rough history, not only of cultural appropriation, but also of paving the way for [outside] governments and other groups to come in and—

Colonize?

Exactly. Or there’s stuff in the news recently, about anthropologists who desecrated burial sites, took bodies of people’s grandparents and put them into museums. It’s a harrowing history. That’s something to navigate as a linguist working with an indigenous community.

That’s why the effort must be led from within the community itself.

Yes, we work with this group of four women and one man, helping to develop a curriculum for them to teach Mayangna in the schools and to teach Mayangna as a second language in parts of the community whose language has been replaced either by Miskito, which is the indigenous language of prestige in that area, or Spanish, or English. We did a lot of that kind of work. It was rewarding, definitely.

How long were you there?

The first time I was down there for about a month and a half. I think I went down six or seven times.

That’s that lot. What’s your tattoo?

This tattoo is the moon. That’s the rabbit on the moon, the shape of the craters.

It’s an erasure of the moon, perhaps? [Laughter]

I hadn’t thought of it like that, but yeah.

If you had the opportunity, would you go to the moon?

I don’t think I would.

Why?

How convenient would it be to get there? [Laughter] Are we talking about becoming an astronaut, or—

Well realistically, neither of us is astronaut material, especially me. But if you could—

I would go to the moon and look back at the Earth and regret not having interacted with it the way I wanted to. Just like I moved to Indiana and regretted not interacting with Idaho.

You had regret once you moved away?

I had been away for three and a half years, and spent my time wishing I was here, wishing I was in the mountains. I mean, I grew up skiing a little bit, we would go to Yellowstone, or the Tetons, so I had an appreciation and all that. But when I went to Indiana, that landscape is void of the alpine.

But you didn’t know what you were missing until it was gone?

Yeah, the forests and the trees are incredible there, but it’s not what I wanted and not what matched my subconscious. Being in Nicaragua had an interesting effect, working with people who had a culture that existed in that same geographical place for hundreds or thousands of years and who interacted deeply with their landscape, it became an unbearable draw for me to go back west. I became acutely aware that, this land, Idaho and the West, is the land that I carry in my mind.

So if you went to the moon, you would look back with regret at where you had been, maybe for not appreciating it when you could?

Once you’re gone from a place it still exists in your memory. Memory is a very deep place, you can manipulate your memories, you can experience them and interact with them, but once you’re away from a place, you’re not going to form new memories. The physical interaction is done. I might enjoy being on the moon for a couple of days, but I think I would look back and miss the planet.

North End

April 4, 2020

James Castle House Artist-In-Residence

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History.