Creators, Makers, & Doers: Kailey Barthel

Posted on 11/2/20 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History

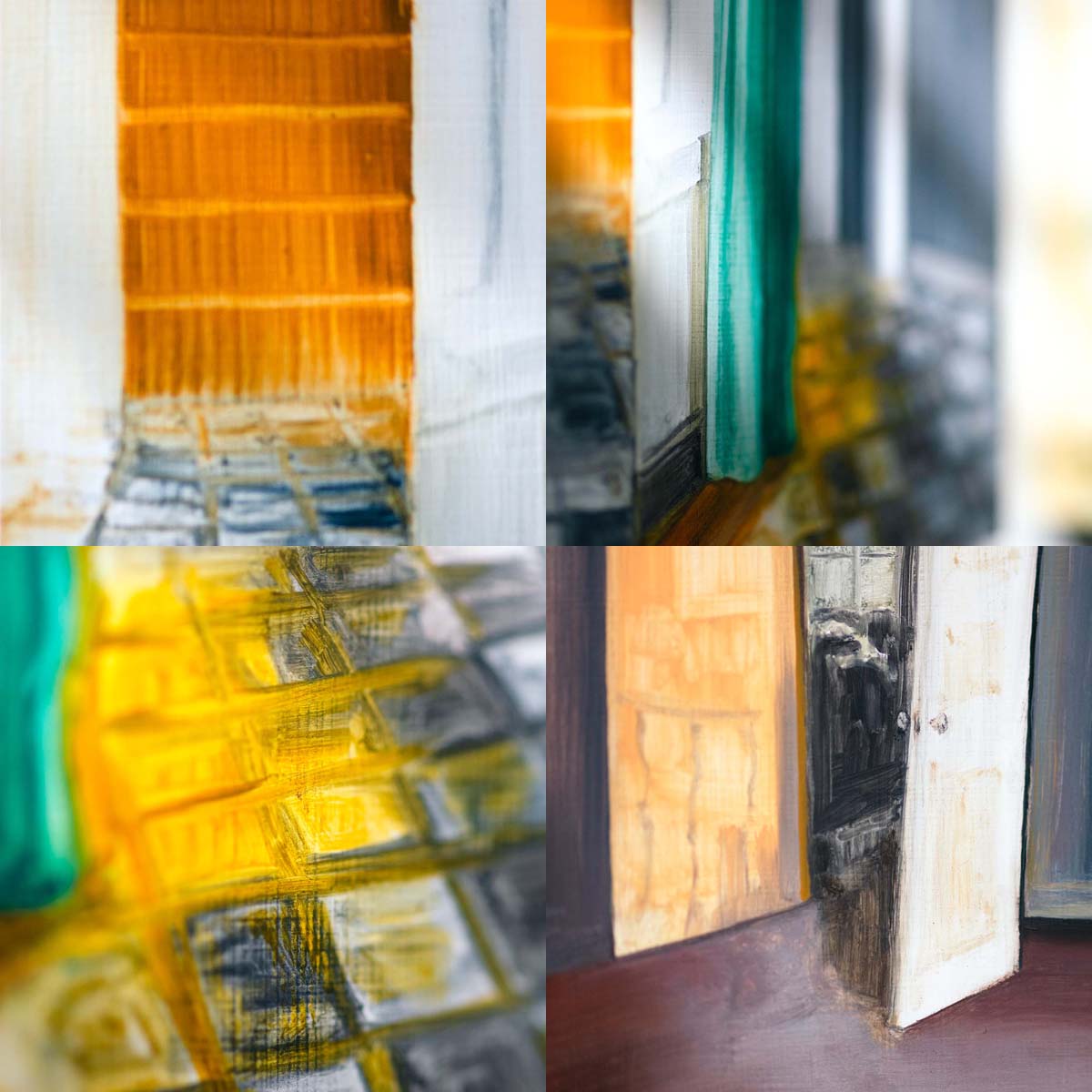

Kailey Barthel, an MFA graduate from the LeRoy E. Hoffberger School of Painting in Baltimore, Maryland, is wrapping up her artist residency at the James Castle House where she’s been experimenting with wood plate lithography in addition to her painting practice. Using imagery from interior design magazines, she collages architectural compositions for new paintings and prints. They have a subtle sense of the uncanny, of vacancy, and a human presence that isn’t visible. Time spent alone painting is half the balance between solitude and community found with other printmakers and studio mates. Surrounding herself with a cohort of artists to share ideas, troubleshoot, and help place her work into a contemporary context is something Kailey needs to make it work, a lesson learned from experience. (We may have talked about zombies and tattoos, too.)

You earned a degree in Latin?

Yes, I started studying Latin in high school. I enjoyed it and thought it would be a good foundation for learning other languages. I kept going in college because I’d already reached an advanced level so it was pretty easy for me to continue taking one class per semester, which I found fun, and I earned a second degree while working on my art. At one point I had the notion to get into archaeology; I’d visited Italy and Pompeii and really loved it. I wish I could say I have kept it up. I’m a little rusty now.

Is Latin a spoken language or only written? I can’t remember.

It’s known as a dead language; there aren’t any native speakers. They use it in Vatican City and a lot of documents in the Catholic church still use Latin.

Are these paintings related to your interest in archaeology?

Are these paintings related to your interest in archaeology?

I think there’s some connection, especially in light of my visit to Pompeii; the rooms I was able to walk through were buried for so long. They provide a little snapshot of what life was like then. There’s something about the little details that survive, the residue of the inhabitants.

Right, because your paintings don’t have inhabitants. They are vacant of people. How would you describe what you are doing?

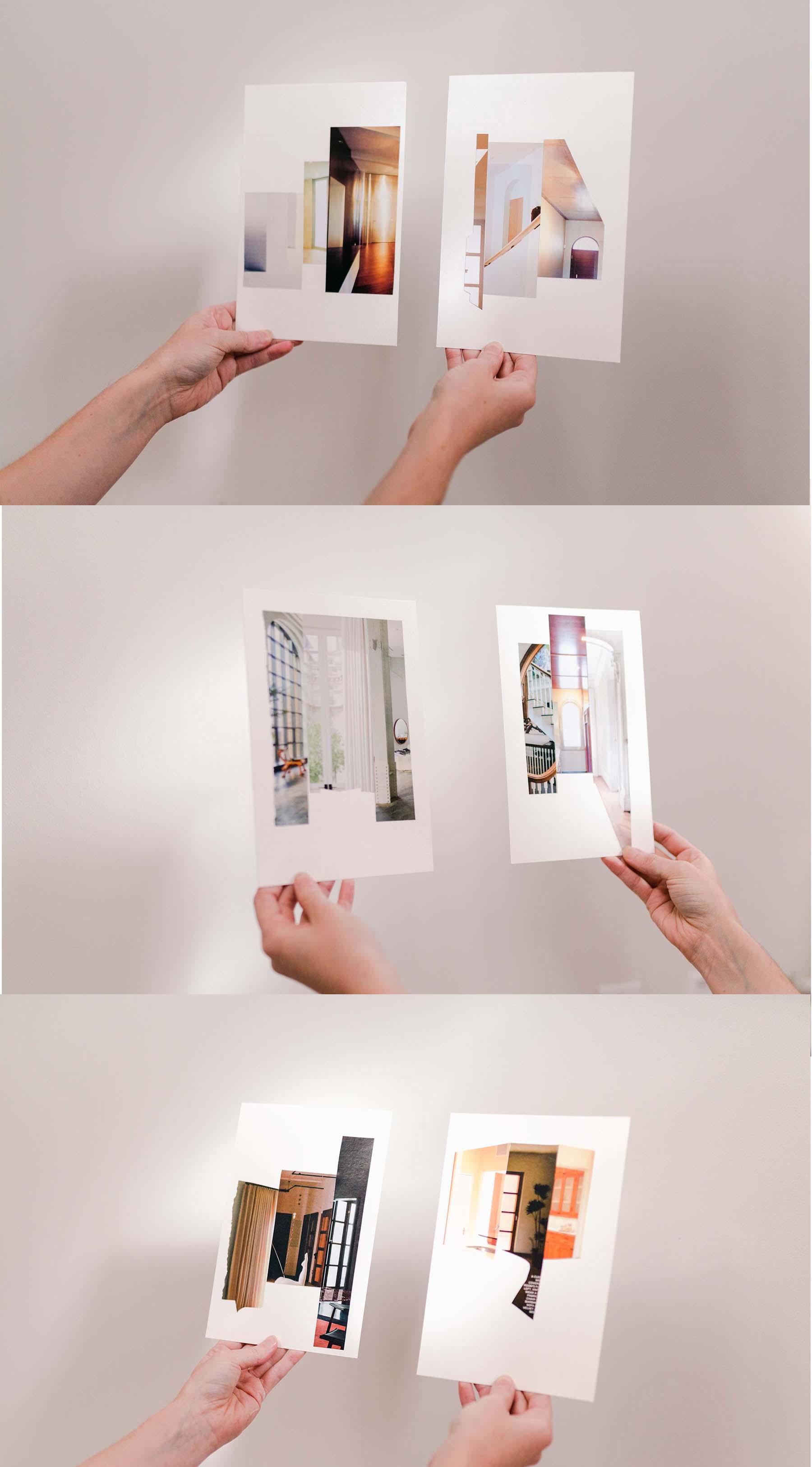

These are small oil paintings drawn from collages I’ve been making. The collages are from interior design magazines and books, mostly domestic spaces. Some are [clearly] different from a home environment.

Or, that they are different from a traditional middle-class domestic space.

Yes, and I started to see how fragmenting a coherent legible space and combining it into a new space can reference something else, like, trying to remember.

Something about memory or the past? Using painting, you blend it into a believable space, at least, more so than the original collage. But it’s clear that the perspective is still not quite right.

Yes, and if we’re talking about the inhabitants being absent, they’re still (present), through a light, like a lamp, that suggests a presence that just isn’t visible.

Like somebody left a light on?

Right. It’s also unclear how long they’ve been absent or how long these rooms have been vacant. There’s a coldness.

I see that. You also wrote about the uncanny?

That’s one of my favorite concepts. I have so much I think about. I think the uncanny comes about in something unfamiliar, a little eerie, that’s in proximity to something familiar. Freud’s essay talks about how even the word is two ideas of home: the unhomely. And how those feelings get formed in familiar domestic settings.

Comfortable?

Yeah, comfortable. I’m also thinking about poets like Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs, their cut‑up poetry, taking a familiar legible text and slicing it up, creating the third mind. You have your mind as the creator and the mind of the original author of the text you’re cutting from; by working in this way, it creates a third presence.

I’ve never heard of the third mind.

I don’t know, we’re getting into like psychoanalytic stuff that I’m not so familiar. I think it’s really interesting and compelling.

Me too. I think there’s also something called the third force.

Say you have a favorite author or lyricist who is deceased, by working with their existing text, you create new work that is theirs also.

Bringing artists back from the dead? Zombie artists. It’s October, by the way. [laughter] What’s on your shirt?

This shirt is an old work shirt, from the Milwaukee Art Museum. When I first started working there, the feature exhibition was Here and Home by Larry Sultan.

How did you get into the arts?

I’ve always been inclined to draw and paint. When I started college, I was undecided, until I took my first art class, then I knew it was meant to be. My parents were not surprised at all. They were very supportive; I am very lucky. I started taking lithography, printmaking. They have an amazing print program at the University of Wisconsin.

Why lithography?

My mother had reproductions of Toulouse‑Lautrec prints, those were part of my early exposure to fine art. I loved those prints and his paintings as well. That’s really why I wanted to learn the process.

Can you explain traditional lithography for people who don’t know?

It’s done on limestone.

It’s like a big rock?

A big rock.

But it’s cut to be flat and smooth, like a tablet. You’ve got to be strong to lift it?

There are some smaller stones you can lift, but they’re still heavy, you have to be careful, they’re expensive. Lithography works on the principle that oil and water repel each other. You draw on the smooth limestone surface with a greasy, oily material, often in crayon form, or a graphic tusche. Then through a process called etching, with gum Arabic and nitric acid, you reinforce the non-image areas, the resist, and the image areas where you’ve drawn that attracts the ink. The ink makes the print.

You roll ink onto the limestone, onto your drawing. The ink sticks only to your drawing then you put paper on top of that, add pressure, and the ink is transferred to paper. Ta-da! And you can do it multiple times, it’s a duplication process. This was invented way before the copy machine. [laughter]

Yes, you use a clean sponge to apply water in a thin layer, so those water molecules stay in the resist areas. The ink won’t go into those watery areas if you’ve done it right.

It’s magic.

It’s like magic. The other amazing thing is you have to wash your drawing out first, and there’s a bit of anxiety because your image is gone.

Completely gone?

There’s a ghost of it, but basically you have to trust the process.

It appears to have disappeared? Thanks for bringing up ghosts, by the way. [laughs]

Correct. But you roll the ink on and the drawing comes back. The printing process is really compelling to me.

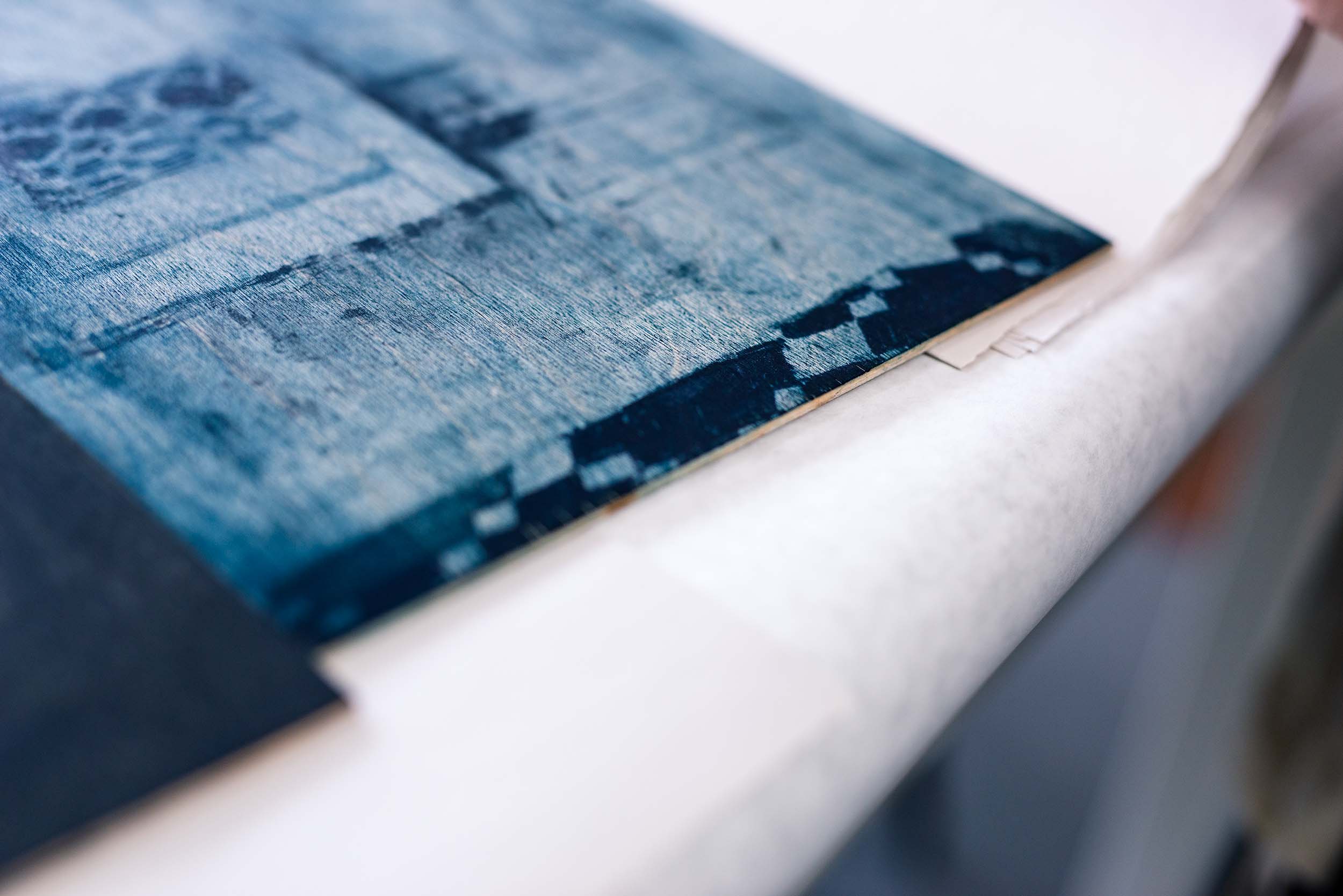

One thing you’re experimenting with is wood‑plate lithography?

Yes, swap the stone out for a piece of plywood. It’s a pretty recent development, in the last couple decades, by a Japanese printmaker named Seishi Ozaku. Japan has a rich history of wood‑block prints and print media.

Where did you go to graduate school?

I went to the LeRoy E. Hoffberger School of Painting at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore.

Did you take a break from printmaking?

There were some challenges in my first and second semesters in grad school where I felt fussy with the marks I was making and needed to take a break; I dove back into printmaking, making monotypes by hand in my studio.

When we talk about mark-making and painting, we talk about the link from your hand to the utensil, like a paintbrush, to the support: paper or canvas, for instance. How is that different from printmaking?

That’s one thing I like about printmaking, the delay between my direct gesture and the final product. Monotypes were a breakthrough for me, there’s a spontaneity and immediacy, and I’ve brought that into my painting practice.

You earned your undergraduate degree in Wisconsin, where you grew up. What was it like to move away?

It was good. I waited three years before I considered applying to grad school.

What did you do for three years?

I explored other interests. I wanted to see if I could keep up my art practice independently without the academic environment; take a break from it. I had a bunch of weird jobs. I worked as the front desk manager at a hostel. I met travelers from all over the world, so that was really great. I did an artist residency for a year in Madison. Then I moved back to Milwaukee and worked at the museum, but I wanted to get back with other artists, and to see if I could push my ideas (further.) I wanted a real cohort and to build a community and language around painting, which is why I love the program I ended up in. The Hoffberger School of Painting is all painters; I don’t have to justify why I’m making paintings instead of sculpture or photography. It’s just a given, that all of us want to be in that lineage.

Just painters?

It was amazing.

I was cracking up when you talked about being an independent artist after undergrad. I did the same thing, and I failed miserably.

I was cracking up when you talked about being an independent artist after undergrad. I did the same thing, and I failed miserably.

Oh, yeah?

I didn’t realize I needed a cohort.

It’s hard to do it on your own. I really need the community around me. As an undergrad you’re able to talk with mentors and classmates; to go from that to my little home studio—that wasn’t working.

Same. You completed your masters degree. Has your perspective changed?

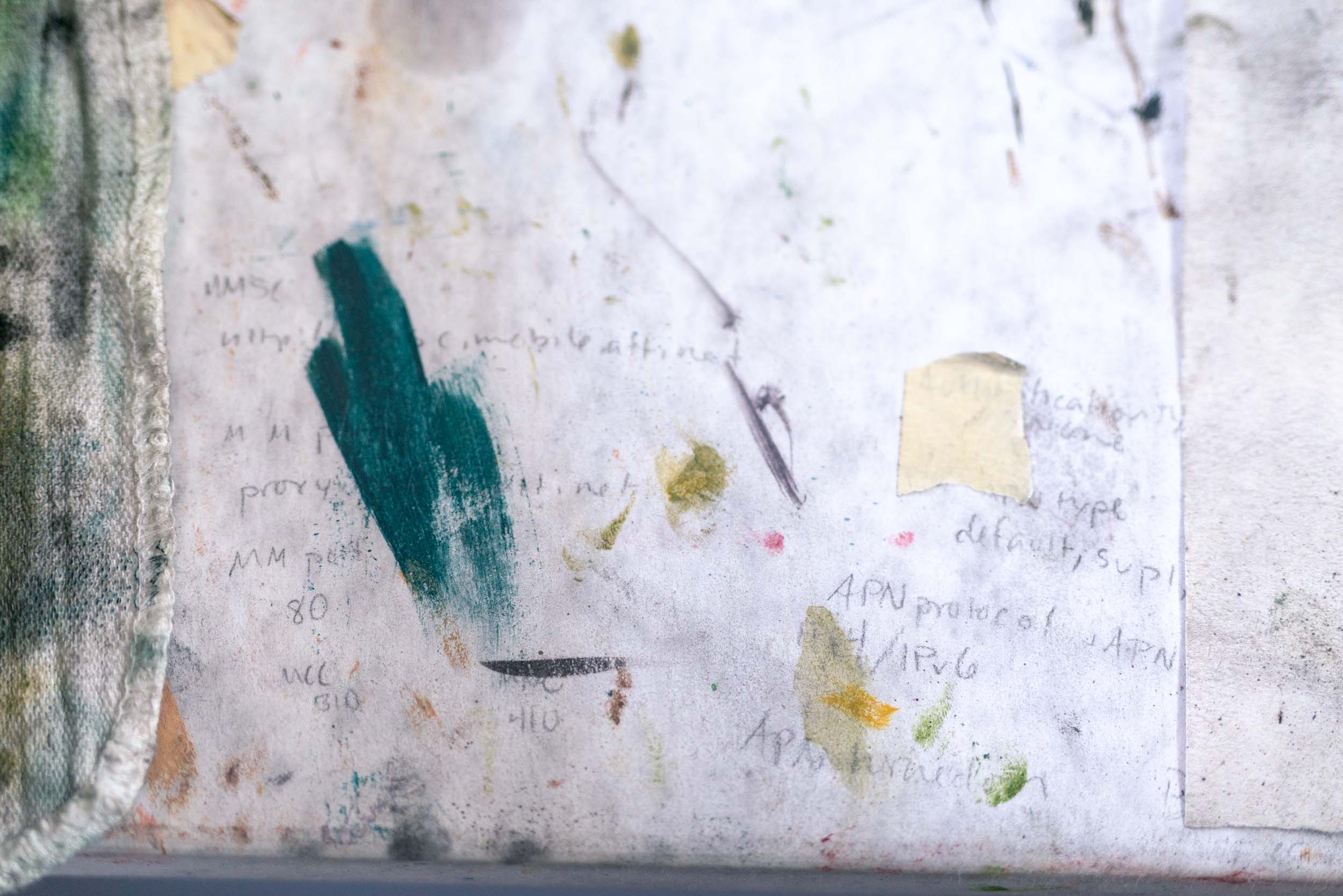

I feel stronger and more confident. I share a studio space with my classmates Luke Farley and Mahsa R. Fard. We found this studio randomly, in Midtown Baltimore. It’s a sublevel in an apartment building with residences above. The girls who had the space before us had a lot of printing presses, so I bought one, and we took over their lease. I go there most days after my day job. I spend as much time as I can there, usually into the night. Often, the most important time is cleaning up and getting organized for what I plan to do next. Like, cleaning the table from the previous night or—mixing up the palette.

I often leave the studio in a mess. Some people tidy at the end, I tidy at the beginning.

At the end, it’s like “This is done,” and I’ve shut the door, “I’m leaving.” Yeah, drop everything and leave. Maybe clean the brushes.

Well, you’ve invested a lot of money in those.

Even in school I was terrible about cleaning my brushes; I’m trying to be better about it.

Do you have a destination in mind for your artwork, or other artists you’d like to show with?

There are so many artists I like. I really like nonrepresentational abstract painting, but to put myself in that context, I don’t know if that’s the best fit. People have commented that I’m basically an abstract painter because I do a lot of geometric abstraction but with something recognizable; architecture, a home, a room.

Which artists do you like right now?

I love all my classmates’ work; my studio mate from Iran, Mahsa, had a digital show in an online gallery space. They are photos taken of her paintings in progress, then through this, I don’t know, AI (artificial intelligence) stuff that she and a colleague built around her work, the viewer can change the paintings. It’s pretty interesting because none of the paintings actually existed, they were works in progress, or, she’ll paint over her work and it will be a different painting; there’s layers.

It’s conceptual.

It’s called Dream Simulator.

One thing we didn’t talk about is your paint application. There are drippy, streaky areas that feel creepy. I’m not just saying that because it’s almost Halloween. I love fall.

There is that vibe. It’s not always melodrama I’m going for, but there is sort of—hmm, an atmosphere of abandonment.

I think it’s the streaks, they are used as signifiers in horror films.

I love old German expressionist film and—I guess I don’t watch much horror, but—cinematic in general, I think is definitely an influence.

Do you feel these are tied to your own personal memory or nostalgia?

In some of my earlier work, I was remembering places I’ve lived in, and I wanted the physical quality of the paint to reference something that’s degrading or in disrepair; a palette that is a little dirty, grimy or rusty. I’m interested in finding the beauty in things decaying around us and wanting to go back to a good memory, but also knowing there were things that were wrong, a little bit skewed.

Something skewed about the memory, maybe.

Also, looking at how something polished and already beautiful can be horrifying. Looking at the two sides of things. I’m always thinking about these things. But [the collage] imagery comes from very slick and elegant interior design magazines. There’s a sense of class.

Money.

Yes. These interiors are not [like] places I’ve lived in. There is something pointing to class that hasn’t really been discussed. Maybe there’s something that reminds me of a place I lived. It could be a literal object, like, “Oh, I remember a lamp like that in a house I lived in” or a pattern on a rug.

Are you an optimist or a pessimist?

Oh, that’s a good question. Let’s see, I guess I’m—hmm—I think I’m mostly an optimist. I like people and humans and the things they make, and I like looking at things they make. So I guess that’s always true. But sometimes I do just want to run away, I don’t know.

What you described ties to being an extrovert or an introvert. Have you ever thought about whether you’re an introvert or an extrovert?

A little bit. I’m just too wishy‑washy, I’m always kind of in the middle, it changes depending on other things.

That’s very common.

That’s very common.

I really enjoy spending time with people, but there’s certainly times when I don’t have the presence of mind to track, so I need to restore myself in private.

Absolutely. What’s your tattoo?

It’s based on a paper‑cutting tradition in Polish folk art. This shape is a tree of life motif. The word is leluje, which I think literally means lily. I love the symmetry and the detail. I have a notion to get another tattoo, something James Castle House related.

Oh yeah? Before you leave?

Yeah, a little commemoration.

I’m so happy right now. What’s at the top of your list for a James Castle inspired tattoo?

I’m looking at what he does with pattern; where the volume of the figure or form is described by the pattern in the background.

We want to be the first to know when you get your new ink, okay?

If it’s going to happen.

It might not happen, but that’s okay. I’m not getting my hopes up. [whispering] I’m so getting my hopes up. What’s a favorite thing about being an artist?

Oh, my goodness. That’s a good question. In my practice, going back and forth between painting and printmaking, there’s a lovely balance between solitude and community. I’m not trying to be prescriptive, but painting—a lot of the time I’m alone in a room doing my thing and seeing what happens. With printmaking, I’m often in a print shop with other printmakers, we can troubleshoot together, or I can see what my friend is working on, or help them sponge their stone. I like that balance.

North End

November 2, 2020

James Castle House Artist-In-Residence

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History.