Creators, Makers, & Doers: Nels Jensen

Posted on 4/15/21 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History

Nels Jensen is a sculptor working with steel and metals and is the owner of Picture This framing, a cornerstone small business in Downtown Boise nestled between Flying M Coffee and Guido’s Pizza. He spends sacred creative time in his Garden City studio, shared with two other artists. Nels’ meticulous attention to detail and high standards set his work apart and above, keeping a hand-built, old-school approach to framing and his emerging custom furniture production. But when it comes to art, it’s got to engage your emotions, positive or negative, even if it makes you uncomfortable. Especially if it makes you uncomfortable. Nels shares unexpected ways he’s seen visual artists affected by the pandemic, and (juicy!) how Boise art collectors spend their hard-earned cash. But at the end of the day, the questions that really matter are: What do you keep next to your coffeemaker? And: Does art really matter? Check out Nels’ answers and decide for yourself.

We just had a nice tour of the studio and you also have a fine art framing business, Picture This.

We just had a nice tour of the studio and you also have a fine art framing business, Picture This.

I’ve owned a frame shop downtown now for about 25 years. It’s how I’ve made my living; it’s where I’ve put my life, my passion. I’m a conservation, high‑end, make-art-last-as-long-as-possible framer. The frame shop has a gallery as well and that’s where I show my sculptures. Hopefully, we’ll be showing some of my furniture there soon.

Is furniture a new pursuit?

Pretty new. Probably in the last year or so. I’ve started to fine‑tune the furniture to the point I think it’s sellable, and unique enough that I’d want to sell it.

Do you have pretty high standards for yourself?

Extremely.

The two pieces here are beautiful; that you say it’s taken a couple years to decide it’s ready to sell, says a lot.

I’m used to having really high standards. It shows mostly in the framing I do. I believe if I’m going to sell work it needs to be as perfect as possible, even though it’s made by human hands, so . . .

That begs the question, if it’s not made by human hands, then what?

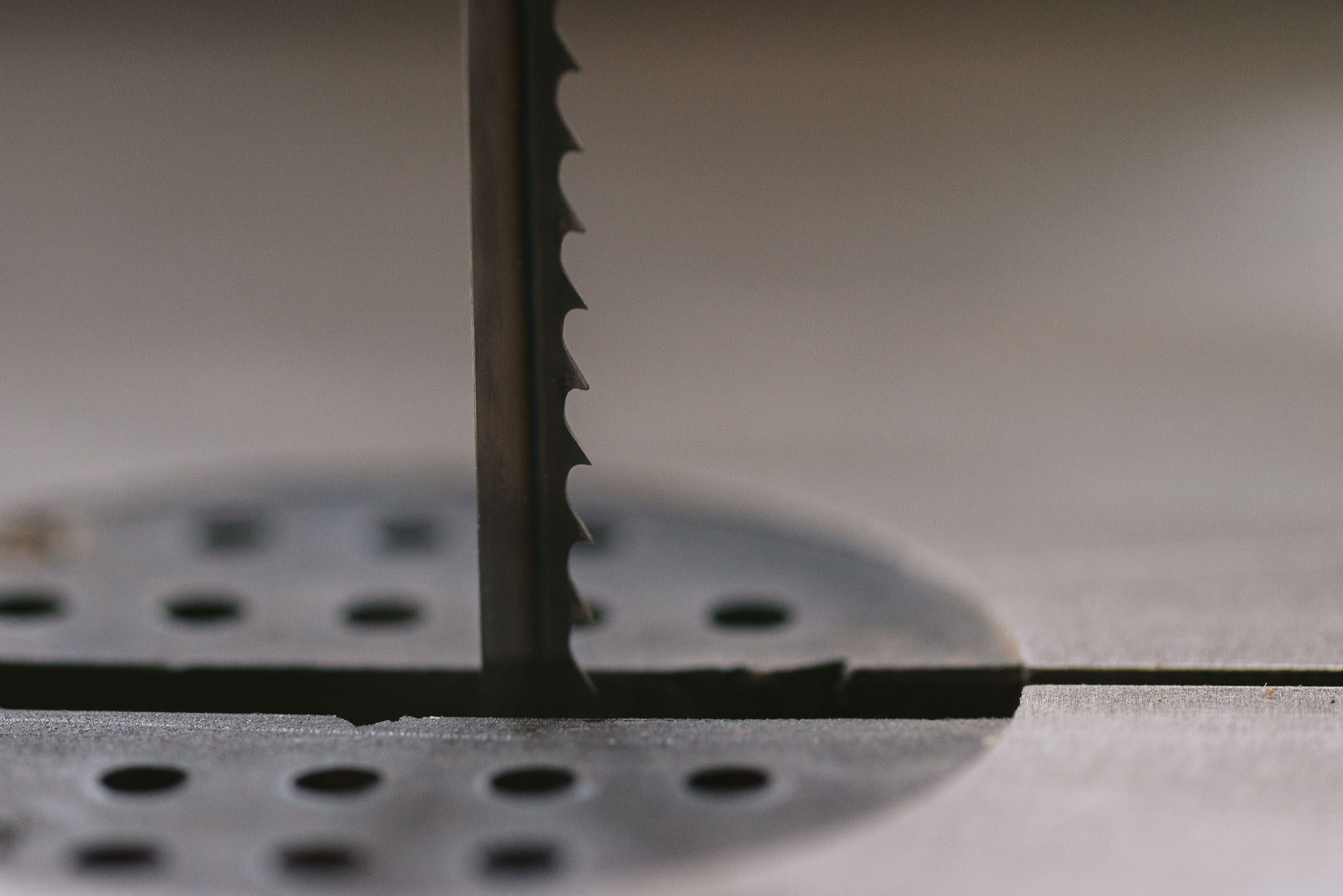

There’s a lot of technology taking over, people expect their products to be built by machines. There are automated CNC routers. There are automated mat cutters. I don’t have them, but in the framing industry there are a lot of machines to produce the materials. I’ve tried to keep things as old‑school as possible. I hand cut my mats. I use vices to join my frames. Honestly, I would rather be doing closed‑corner frames with carved corners and accents.

Right, you showed me a frame with a carved design. A goat. There are a lot of goat motifs in here. And a lot of skulls.

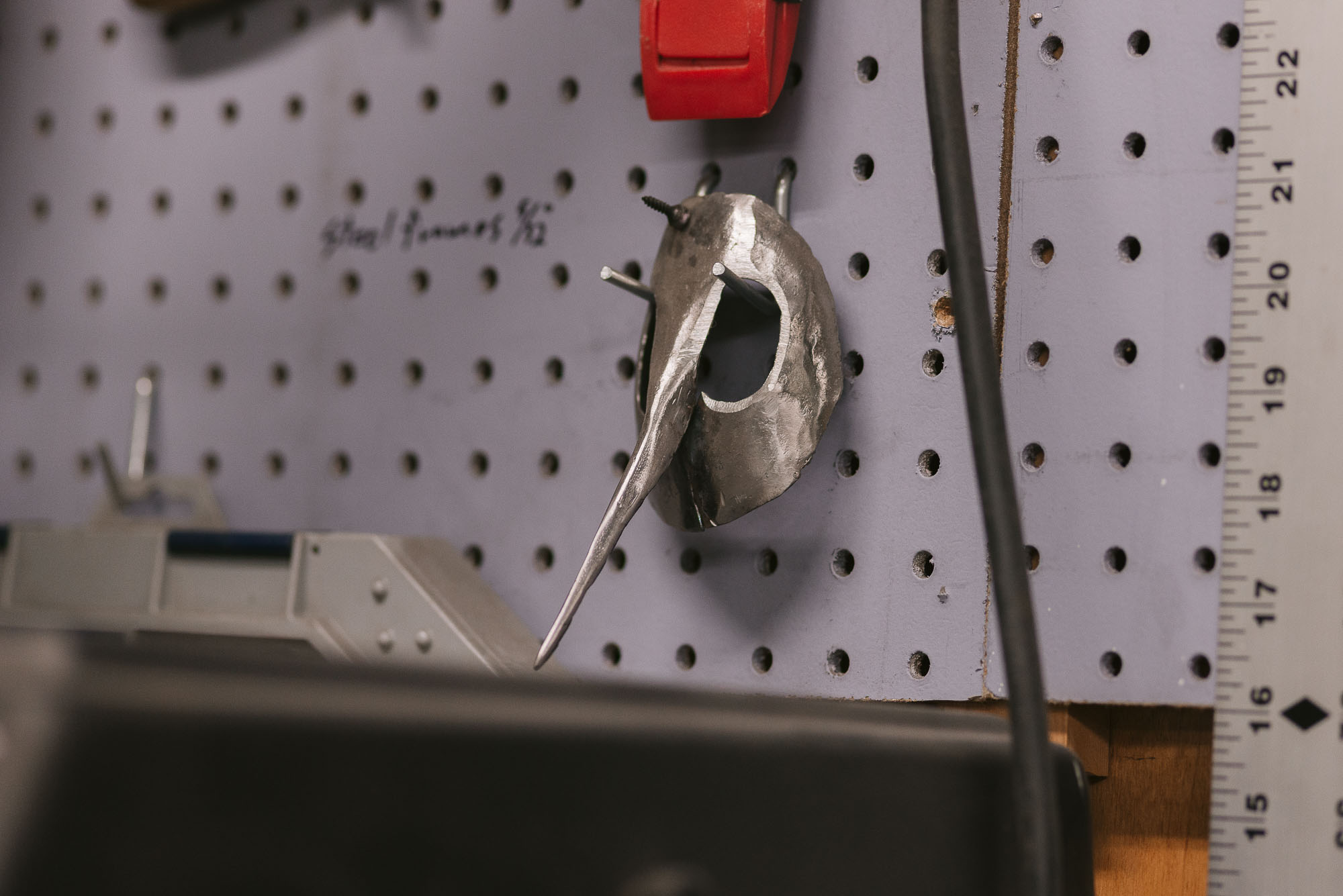

There are a lot of skulls in here. I have a tendency to collect animal bones. I also like to sculpt them. The big skull with the horns was for a show at the Visual Arts Collective in Garden City. It’s specifically about Krampus. If you’re not familiar with Krampus—he’s kind of the anti‑Santa Claus. Santa Claus will bring you gifts if you’re good, but Krampus will steal you away and beat you if you’re bad.

Uh oh.

Uh oh.

I did a whole series of animal skeletons. So, yeah, it’s a fascination of mine. I like the infrastructure of the organic.

You say infrastructure and I think skeleton and skin.

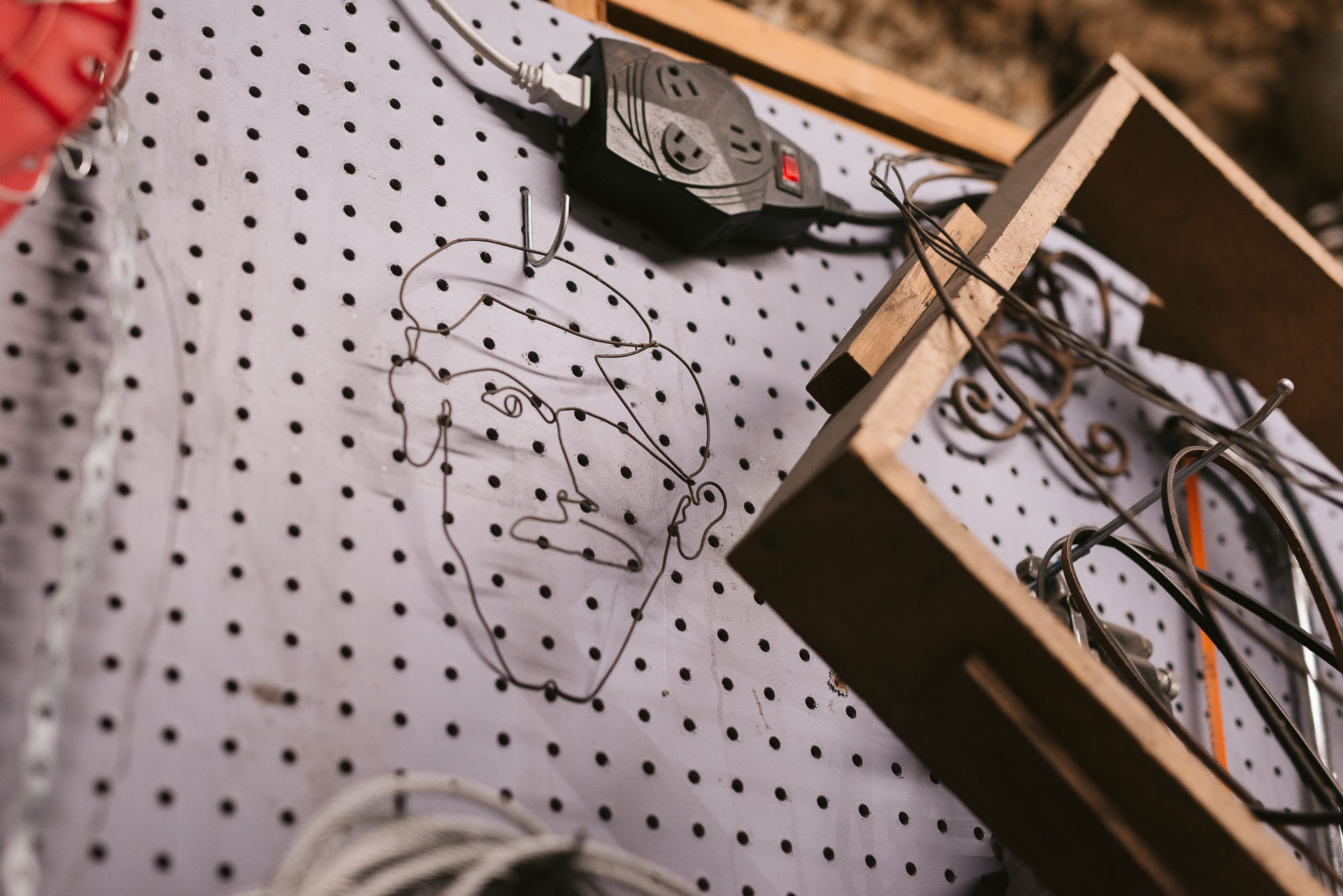

If you don’t understand the framework, you don’t understand how it moves. You don’t understand how it works. A lot of my sculptures are studies for a finished piece. Good painters, if they’re going to draw a human body, start off by drawing the skeleton so they understand where the muscles are supposed to be. As a sculptor it’s the same thing. I need to understand the base work to understand the exterior. I’ll do several sculptures of the interior before I do the outside, to understand what it is I’m supposed to be doing. One of the driving forces behind my artwork; is to try to make things look impossible. I did a whole series of floating steel blocks, I suspended them from very thin braided cable.

So that it appears to be physically impossible? Or at lease implausible?

That little table is one of those things. I wanted it to look like the legs themselves wouldn’t be strong enough to hold anything.

And it does, it appears elegant and delicate. Plant-like. I thought to myself, “Do not touch that.”

It looks fragile, but it’s not. That thing could probably hold 200 pounds.

No!

Yeah [chuckling]. That’s why I do it.

What’s your attraction to the impossible?

I think it stems back to—my father was a pilot, and it always seemed impossible that you could hang in the air, in the middle of a piece of machinery that weighs several thousand pounds. Coming at sculpture, thinking about things from an engineer’s standpoint, trying to figure out ways to use physics to try to create something that seems impossible.

Use physics to break physics.

Use physics to break physics. I started off as a painter—there was always this idea, to make something look like it’s there, when it isn’t.

An illusion?

Creating an illusion. Then I found sculpture and realized I didn’t have to pretend I was building something, I could just build it. And it was easier for me, so I’ve always felt a little lazy.

Lazy? [laughter]

That I chose sculpture over painting, because it seems easier to me to make a three‑dimensional object. One that you can pick up and turn over and say, “Oh, that line isn’t right, I need to adjust it.” Rather than to draw a line and make it look like it’s supposed to look.

I’m glad that you’re working in a medium that comes easier for you. That’s not the case for everyone.

I got tired of staring at blank canvases trying to figure out . . .

What to do with all that white space? [laughter] You bring up an interesting point about leaving behind the pressure to create an illusion. Those are my words. I don’t know how you would describe it.

It’s not so much leaving it behind; it’s just a different type of illusion. You know, instead of—instead of creating an illusion with a painting that there’s an apple sitting on a table. We were talking about Geoff Krueger and his work; his paintings where it looks like there’s a spoon taped onto the surface.

It’s trompe l’oeil.

Right, until you walk up and almost touch it, then you realize it’s actually the painting. With sculpture, it’s a little bit harder and a little bit easier to create that illusion. You know, by simply taking a flat panel and turning it sideways, all of a sudden it looks very, very thin and unsubstantial. You can use that to your advantage.

Tell me about these bees.

The point of the bees was to take something we equate to a very heavy material, steel, and take something that shouldn’t be able to fly in the first place, a bee—my goal was to make steel look light enough that it could be in flight. It’s proved to be extremely difficult. I have one that I’ve built over and over and over again and making the parts thinner and lighter, trying to create that feeling of flight.

Of weightlessness. How about the armadillo?

The armadillo started—I have a client who purchased a piece probably, 12 or 14 years ago. I built a bird out of all of the reclaimed razor blades from the frame shop. Every feather was a razor blade. The wings were built out of Morso chopper blades, a Morso foot chopper is what we used to chop frames with.

The 45‑degree‑angle‑cutter thing?

Yeah. The wings are those massive Morso blades, and the rest of the feathers are tiny little blades. Then I figured out that everybody was going to cut themselves on it.

Because people like me want to touch it? [laughter]

Because everybody has to touch it and say, “Are these really blades?” So I built a cage around it. My favorite client bought it.

Who’s your favorite?

My favorite client is Mardi Wilburn, she’s an amazing human being. Mardi has the bird. She and I got to talking about how we usually equate feathers with being super light—

And soft.

Yeah, and I made them sharp and heavy. We talked about things that provide their own protection and it led me to armadillos and pangolins. We think of steel as something hard and protective, and an armadillo—they’re kind of soft, right? I don’t know if you’ve ever been around armadillos, but their shells are almost, like, squishy, like basketballs.

Um. No, I haven’t touched an armadillo. So, maybe?

It does work as armor and I was thinking it would be fun to build one out of steel. And how do you do that, right? How do you form steel into that shape and get all the pattern. It stuck in my head, I was waking up at three in the morning thinking about it, so I figured I might as well do it. Get it out of my head.

Do you share this space?

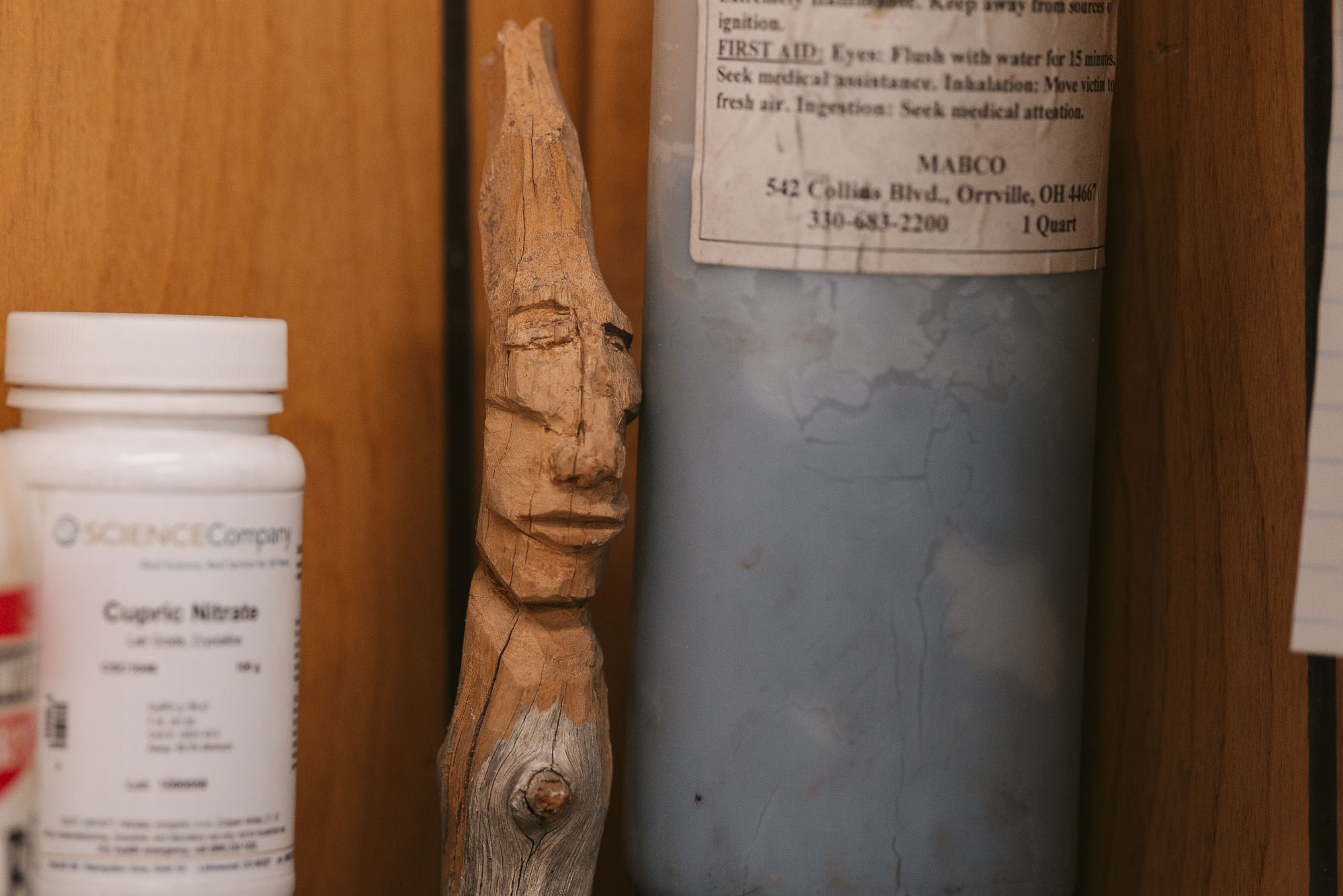

I do. With Saratops McDonald, who is a sculptor, another amazing human being. I also share the space with Sam Stimpert, owner of Visual Arts Collective. He got me into casting; I cast bronze and aluminum. I have a foundry at home that I don’t use often because I’ve become enamored with steel. I still do small aluminum castings as accents on sculptures. I have all of the materials and tools to pour bronze but haven’t been using it much lately.

Casting and pouring bronze and aluminum is a pretty big deal. I see this little vessel, with the lid and the frog on the side. What’s the story?

It’s rejected casting.

What’s that?

It just means there’s flaws. It’s something I couldn’t sell.

It looks like it’s on a shrine here.

A little bit. I’ve only cast iron maybe three times in my life. I’ve had relative success. Iron’s an extremely difficult medium to cast. The melting temperature is about four or five hundred degrees hotter than other mediums you cast. To get it into the form properly and actually pour without freezing up is extremely difficult. This was one of my more successful castings. I’ve sold a couple of iron pieces over the years. I have large iron castings at home, but all of them were slightly flawed [in process].

This one you keep right by the coffee maker, so you see it everyday.

Every day.

I put things that bring me some kind of pleasure or meaning to my life right by the coffee maker.

Yeah. I guess the best way to describe it, is, I think of myself as a process artist more than anything else. I am enamored with what it takes to make the things, not necessarily the end result. When it comes to pieces that don’t turn out the way that I originally thought, it creates a lot of problems for me to solve. I think of my art as therapy more than anything else. Having this flawed iron piece next to my coffeemaker makes me think about all the different ways we can approach the next iron pour, and whether or not I could be more successful at it.

Maybe not just art‑making but life.

Most definitely. My father started calling me the starving artist when I was about six or seven years old because I was always building. Always painting. Always drawing. Always trying to figure out something to do with my hands. When I say my art is my therapy, I mean it. I’m one of those people that needs five or six hours a day alone. This is my space. I come down here, I lock the door, I put my headphones on, and I build. It allows me to have problems that aren’t real‑world problems. I’m not thinking about taxes, I’m not thinking about bills, I’m not thinking about relationships, I’m not thinking about anything. I’m strictly trying to figure out how to take a particular medium and turn it into something beautiful.

And a sacred place. How do you see the pandemic affecting artists?

So the pandemic did a really strange thing for artists that I wasn’t expecting. I assumed every artist was going to be starving, we were all going to go back to, I don’t know, waiting tables and working at banks. But my experience at the frame shop and gallery has been, that because people aren’t traveling and aren’t renting hotel rooms and not eating out, they have extra money that’s been earmarked for personal happiness. So, the artists I know, who are out there pushing themselves on social media or have their work displayed in galleries, or are still out in the public eye—their sales have actually been better than anticipated; not because their work’s changed, but because people have more money to spend on things that help make them happy through this pandemic.

Their options of how and where to spend that happy money have become constrained.

Limited, but it’s working to our advantage because it’s local. Because they’re not getting on planes flying to San Francisco and buying artwork there and shipping it back. They’re actually wandering around their own towns, looking at people who are local and saying, “Look, this artist is producing amazing work, and I didn’t notice them before.” Art sales have been up, from my perspective. I know a lot of artists aren’t as fortunate; they don’t have the space that I have. My wife is a ceramicist, she normally does big shows—Sun Valley, Park City, Jackson Hole—and that’s where she makes her money. All these shows got canceled and we thought her income was going to suffer drastically, but sales out of the frame shop and her sales from what she posts on Instagram have been tremendous in comparison.

Direct sales from her website?

Yes, but my friends who own art venues, bars, restaurants—they are struggling. I cannot—

Like the Visual Arts Collective. It’s terrible for these venues.

My frame shop is booming because people are focusing on their own homes—home renovation industries, anything to do with gardening, or the yard, RVs—

Sprinter vans.

—Sprinter vans, that stuff is booming. The frame shop is doing great and I didn’t expect it. I thought I was going to have to cinch up my belt for another economic downslide.

That is so interesting. How about creatively? You said you need six or five hours a day alone anyway.

The joke I was making when the pandemic hit, everybody was, “Oh, my God, I can’t go out to eat, I can’t go to the bar, I can’t go—I can’t travel!” I was saying, “Well, my life really hasn’t changed at all. I’m framing pictures and going to my studio and making stuff,” that’s what I do. Emotionally I didn’t feel starved for company, I look forward to my time down here more than anything. I’ve gotten more time in my studio than ever, I don’t have other obligations.

I’m wondering if the pandemic is going feed into the why and what you make art about. Will it creep into your inspiration?

Possibly. Most of what has come out of the pandemic that has affected me, from an artistic standpoint, has been a little negative. Primarily because we live in the United States, and we are very self‑involved people. I’m including myself here, too. We don’t want to wear masks and—I mean, I am a strong advocate for protecting the people around you. But as a nation we don’t want to wear masks because it’s a personal affront on our liberties. When the reality is you wear the mask not for yourself, but for others. I would like it if we were more like Japan, where if people get a cold, they wear a mask to protect the people around them. This allows people to continue to work and do their thing. I’ve watched people down at the capitol building—

Oh, right, people walk by your business—

I’m two blocks from the capitol building, so I’ve been watching anti-mask rallies and people harassing businesses downtown because [the business is] complying with City ordinance. People acting like they’re having their rights taken away from them because they’re being asked to wear masks to protect the people around them.

It’s been interesting for sure.

My son had cancer when he was two. We went through about eight months of treatment, everything that comes along with a kid with cancer. You go through that, and you realize not everybody has perfect health. There are a lot of people with heath issues. If I were to refuse to wear a mask, and gave somebody COVID, who had issues with lungs or heart, and it killed them, I would feel that for the rest of my life. I don’t understand how the rest of our society doesn’t think that way. But I know it’s because of my experience.

You’ve learned a lot by being personally affected because someone you love deeply is high‑risk. You really know to your core what that means.

Yes. And as an artist, I’m not always trying to make people feel good, I’m just trying—let’s start off with my definition of art.

Maybe should have started there at the beginning.

[Chuckling] Right. Art, in my definition, is something that creates emotion, period. It doesn’t have to be positive; it doesn’t have to be negative, it doesn’t have to make you feel good, it doesn’t have to make you feel bad. There’s amazing artwork that I would never hang in my house because it makes me sick. It makes me nauseous. It makes me uncomfortable. It makes my skin crawl. But if a piece of artwork can give you a physical reaction, that is some of the best artwork you will see. The majority of the artwork that sells does make you feel good. It makes you remember something beautiful or makes you think of a good time in your life. It reminds you of somebody that influenced you.

Or it reflects something about yourself back to you. [coughs]

Right so that’s good art. But it’s not the only good art out there. Thus, a bird made of razor blades—not necessarily a warm and fuzzy feeling. I’m not saying I want to create artwork to make people feel good all the time—

I’m not seeing a lot of warm fuzzy around here.

But I do like for art to create some kind of emotion. That’s why furniture building has been a harder for me, because it’s not an emotional—it doesn’t make emotion.

I disagree. Both pieces in the other room create a sense of stability and calmness for me. Is that an emotion? Like a very mellow sense of joy.

Well, that’s good. I’m trying to make it unique and make it look impossible. At least that’s something to think about.

With the impossible, you’re adding tension. Now what about art that makes your skin crawl?

There’s a female artist here in town who almost exclusively paints paintings of women post rape. They are the most disturbing images I’ve ever seen; bruised, bloody, battered, angry. Hard to look at. If you can get past the image itself and look at the paintings for what they are, they’re amazing. Art doesn’t have to be beautiful, but it does need to create emotion. From that standpoint her artwork is amazing and beautiful. I would never, ever want any of that in my house, though.

You wouldn’t want that above the coffeemaker?

No. There’s a visceral reaction to that artwork. That’s just one example.

That’s a great example.

Another one is Dan Scott, who is a professor at BSU, his work is unbelievably beautiful. He is the epitome of master when it comes to color. Every brush stroke—

—the texture. Or lack of texture. Composition.

Right? Everything he does—I love it—he does not always work with the comfortable. He has several series that make a lot of people very uncomfortable. I’ve hung his work at my gallery and had mixed reactions. He paints for painters. He paints for people who understand what it is that he’s doing. He doesn’t necessarily paint for the viewer. He’ll do a very intricate, detailed painting of a doily, then below it he’ll paint a nude man in a ball gag with hands tied behind his back. The figure study of the man is just as beautiful as the brush work put into the doily.

His technical skill. His vision, his style.

But the subject matter can be a little disturbing.

He’s treating the figure study and the object the same way. Hmmm.

I have collectors of my own work that thrive on that stuff.

It speaks to them emotionally.

Not every piece speaks to every person. Having owned a frame shop for 25 years, I can tell you that people’s choices in artwork is very much a personal thing.

You get to see how people spend their money. [giggles]

It’s kind of amazing, honestly. It’s one of the things that’s kept me in the industry. I’m surrounded by art, I’m surrounded by artists, I’m surrounded by collectors. So, there’s a large percentage of population here who makes sure to keep their artwork very safe, very clean, pretty. And it can feel like they’re collecting artwork to get approval from whatever guest comes into their home. There are also people in this town who collect art specifically for themselves; they have no intention to show it off or get anybody’s approval. That artwork is very different. There are also people who collect artwork specifically because it was made locally, they’re more concerned with having a piece from each artist in town, than they are having pieces that truly show who they are as a person.

They are interested in a broad, representative collection.

Yes. They want to be able to say they have a Sue Latta, a Mark Bangerter, an April VanDeGrift. Check, check, check, check, check. They want every single Boise artist they’ve run into. Quite a few people do that. They have the resources and ability to make a serious collection. And those are my favorite clients, honestly, because they’re concerned about art. They are concerned about the production, the sale, they want artists to continue to make art.

Who do you collect?

We have a bigger art collection than we have walls. Our art collection—we can show about 25 to 30 percent of it at a time. It’s stored in closets and under beds and wherever, we change it out every three to four months. We’ll rehang the whole house so we can enjoy a different part of our collection. Collectors all have different motivations, for sure, but I believe art is what makes a society whole. If we don’t keep artists producing, we lose what it means to have a rounded society.

That makes me feel better because I had a mini crisis just this morning, thinking “Nobody cares about art.” And wondering what I’m doing with my life.

Every time I hear the government talking about stripping the art programs from schools, I’m furious, because without encouraging artistic integrity we are going to lose [so much]. We can’t live in a strictly utilitarian world; the human mind is not set up for it.

Please no.

April VanDeGrift, art professor and amazing painter who also works for me; the conversation she and I have all the time is how important artwork is to the society we live in. Every time somebody says, “Art isn’t important, we don’t need it,” then, I would say to them “You need to throw away your phone. You need to throw away your TV. You need to realize that everything you wear, everything you listen to, everything you look at, everything is there because we have artists.” We need art for all advertising, commercial ventures, design. The people who designed our phones, the chairs we’re sitting on—I mean, every architect out there, every engineer, they’re all doing a form of artwork. Every chef. Every musician. Every painter, every sculptor. Every writer. Every photographer. All these people we depend on to get our information to us, they are artists.

I feel much better now. Thank you.

Downtown Boise

April 12, 2021

Public Art | Care and Conservation

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History. The views expressed in this publication are those of the individuals interviewed and do not necessarily reflect those of the City of Boise.