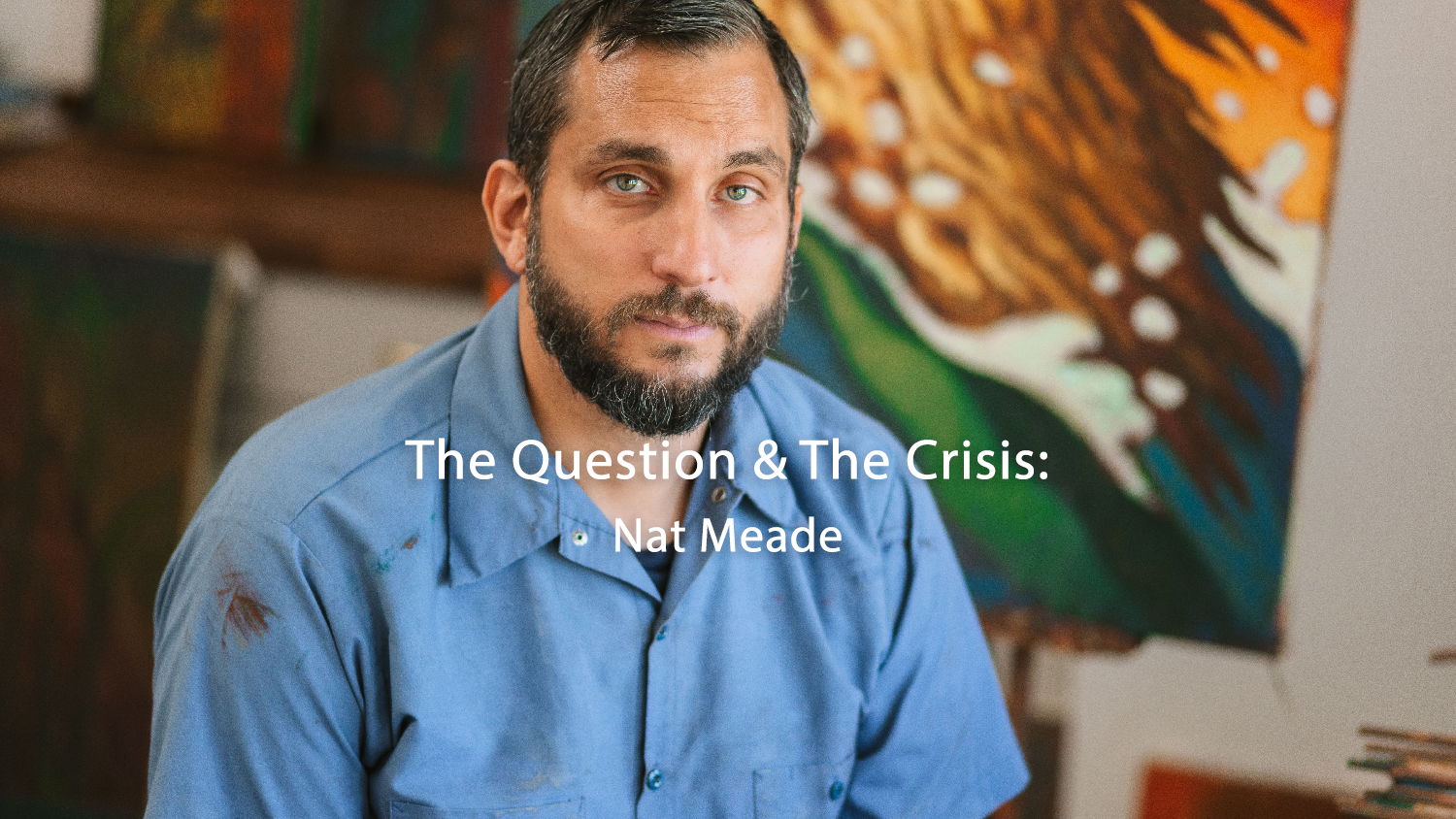

Creators, Makers, & Doers: Nat Meade

Posted on 7/14/21 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History

For Nat Meade, coming to Boise as an Artist-In-Residence at the James Castle House means returning to the memory of his time at Boise State University where he attended college on a football scholarship. Now, with a graduate degree from Pratt Institute and a family of his own, he reflects on tough decisions when it comes to deciding who you want to be and the uncanny feeling of looking both backward to childhood beliefs and forward to an evolving worldview. He addresses these kinds of complexities in his figurative paintings informed by American Regionalism (there’s a lot more to that story) and hints at the comfort and the danger found in male archetypes. He calls them gods and buffoons. Nat lays down some of the best advice he’s received as an artist, and surprisingly, it has to do with following your weaknesses, not your strengths.

This isn’t the first time you’ve been to Idaho?

I came here on a Boise State football scholarship for three and a half years.

Only three and a half years?

Playing football was so all‑consuming, I couldn’t take time off because, in my case, I would lose weight. I had friends who were traveling and experiencing things you can only do at a certain age, in your early 20s. I also felt a conflict because I knew I wanted to be an artist, which also takes dedication. I was pulled in two different directions, there wasn’t a lot of space to grow up and explore. Also, at the time our coach, Pokey Allen, who I liked very much, had cancer. He ended up passing away from cancer.

That must have been rough.

The team was kind of falling apart, there was a dark side.

The dark side to living the football dream?

I had enough of it. It was very hard because I identified as a football player, I wanted to prove to myself that I could play and get on the field. But I gave myself permission to leave.

That’s a big step. Did you leave a lot on the table?

I redshirted my freshman year, which means my scholarship was extended because you redshirt for a year to five years.

Did you have support in your decision?

Things were pretty hard at home. I was having a hard time concentrating on football and academics was an afterthought. It wasn’t a happy time. So, I took time off, I worked, I traveled to Europe and saw all the amazing art.

It seems like two different lifetimes you just described.

I learned a lot. It helped me prioritize my life, what I wanted to focus on, the person I wanted to be. I didn’t want to identify as a football player the rest of my life.

That’s what I’m hearing.

But I met good people. There’s nothing I regret about it. I’m happy with the decision I made and where it led.

You went through what you had to go through. Did you continue your education?

I went back to University of Oregon, not a traditional student age anymore. I found an amazing mentor, Ron Graff. He influenced a lot of artists who came through the program. He was pretty hard on his students and he took to me. I think he recognized that I could take it. [chuckling]

Not get your feelings hurt?

I really wanted to get better, I just wanted to learn more. I had great teachers at U of O, Carla Bengtson and Laura Vandenberg.

And you went to Europe?

That was huge. It was really eye‑opening.

You got to see the things you’d studied in art history. Which historical periods do you gravitate towards?

In my work, the imagery that influences me comes from 20th Century American paintings, Regionalism. Artists such as George Tooker, Paul Cadmus, Grant Wood, John Steuart Curry, and Thomas Hart Benton. Also, Forrest Bess and Ryder, also an artist named Albert York, based in Long Island, who has an interest in mythology. But when I was in Europe, I looked at everything. The paintings that knocked me out were in Naples, Italy, the Peter Bruegel the Elder paintings.

Why?

The Blind Leading the Blind is probably my favorite painting ever, at the Capodimonte Museum. I turned a corner and saw that painting. I didn’t know who Bruegel was. I’d never seen a painting do what that painting did.

What did it do for you?

Bruegel presents a world—it’s not like a Cézanne painting, responding to nature. He’s presented his own world.

Bruegel didn’t respond to the natural world? Not an attempt at objectivity?

It’s subjective, but it’s also convincing, the feel, the mood, the atmosphere, the figures. That’s what I look for, I’m always struck when an artist can present a world—

Of their own invention? Is it staged?

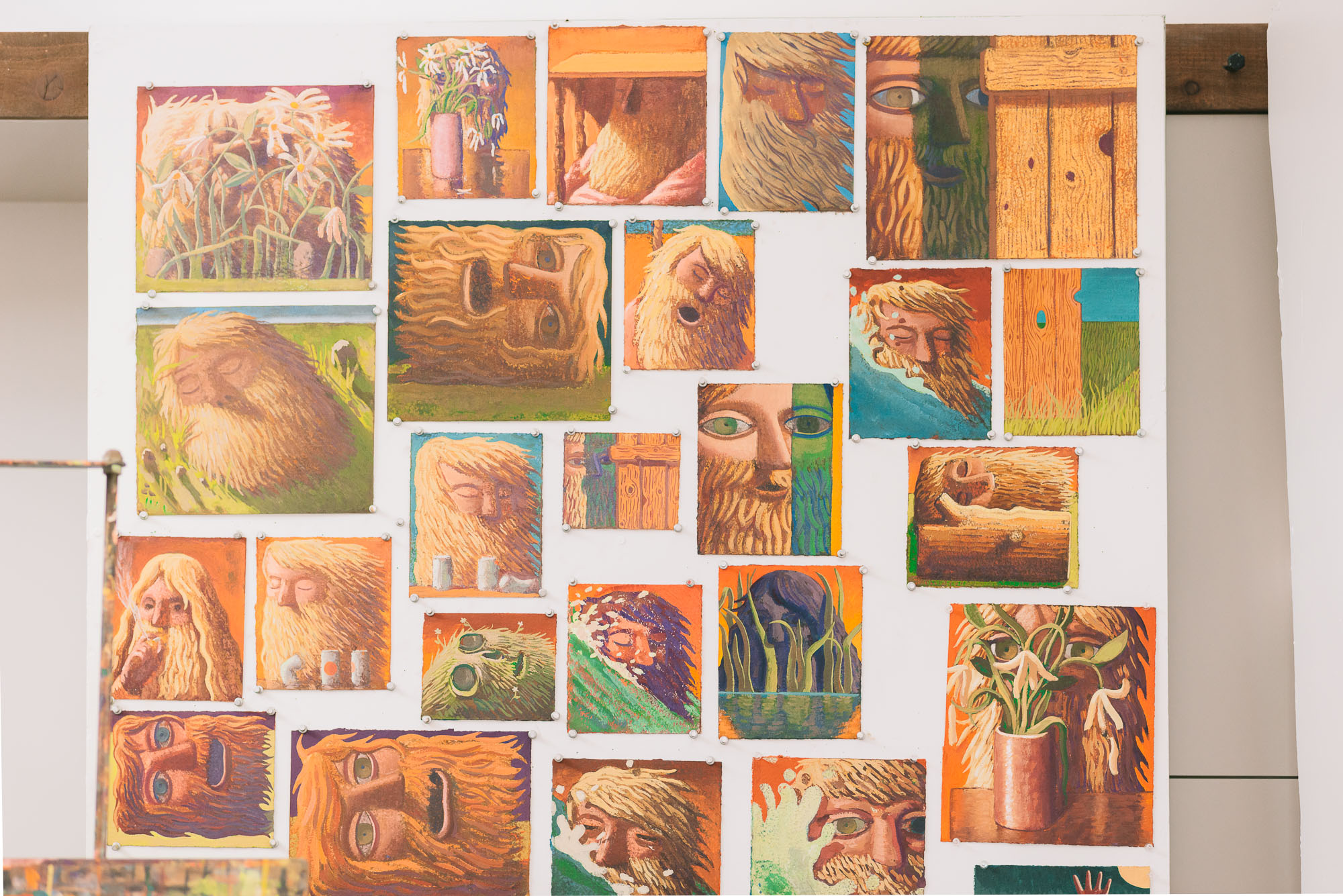

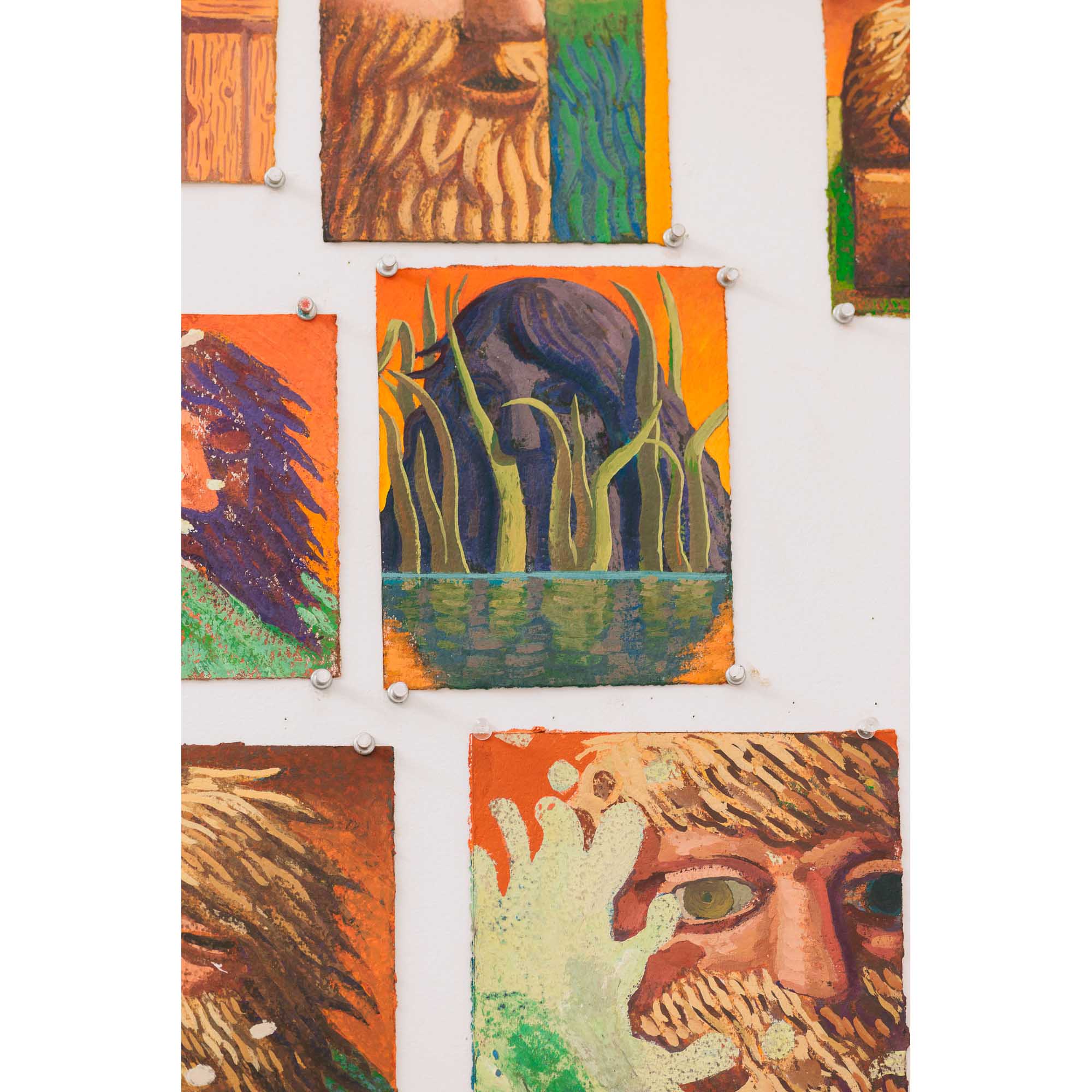

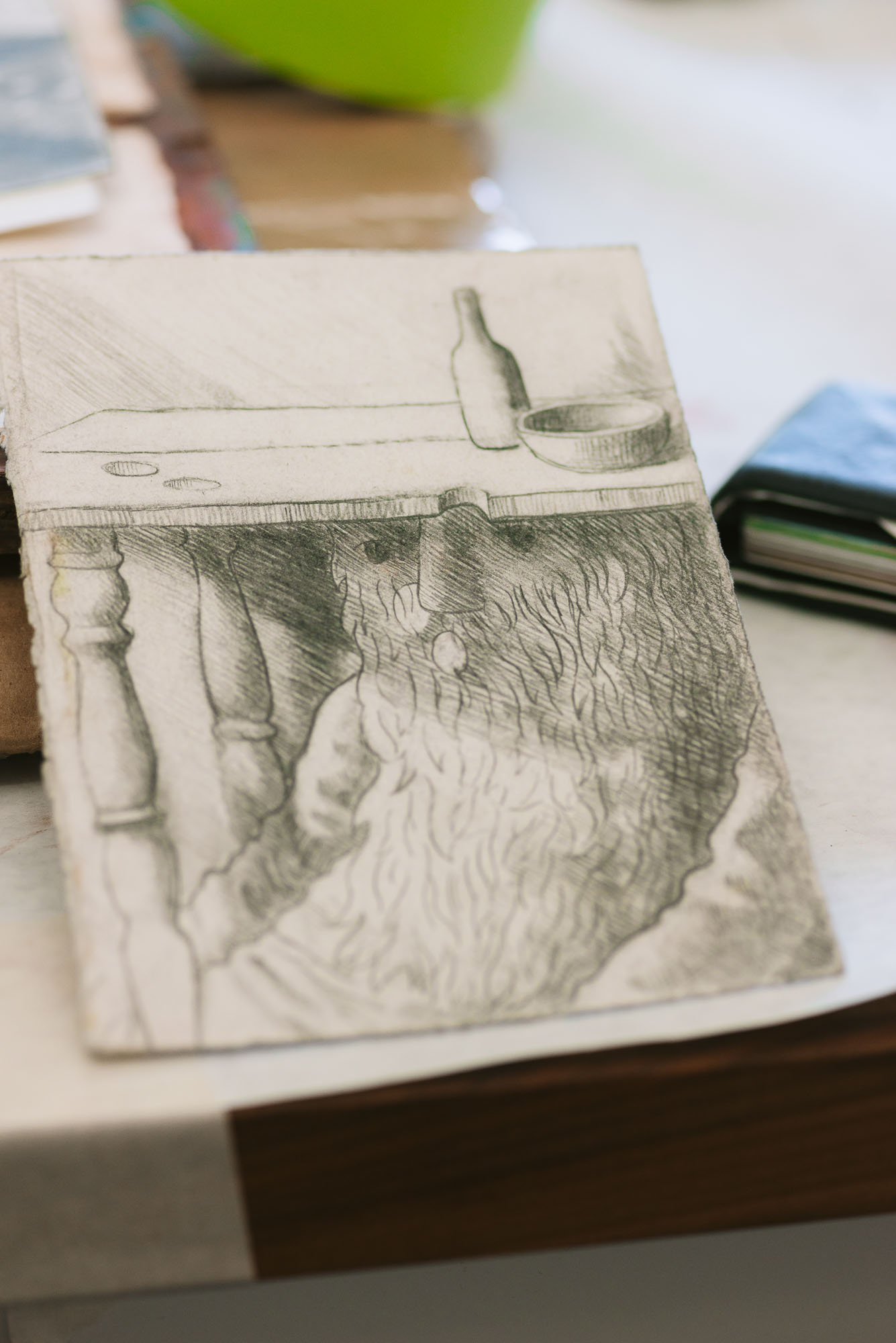

Not exactly, but I’m interested in the staged quality. In my work, my figures all fit into this rectangle and the rectangle determines their proportions. It’s all very frontal, in a shallow space. The confines of the canvas restrict the space and the figures

And the world. There’s also something to be said about the direction of light and the way the shadow falls. It’s a little theatrical.

I think so. It’s controlled.

Let’s talk about the use of the figure. What’s the deal with these guys? [laughter]

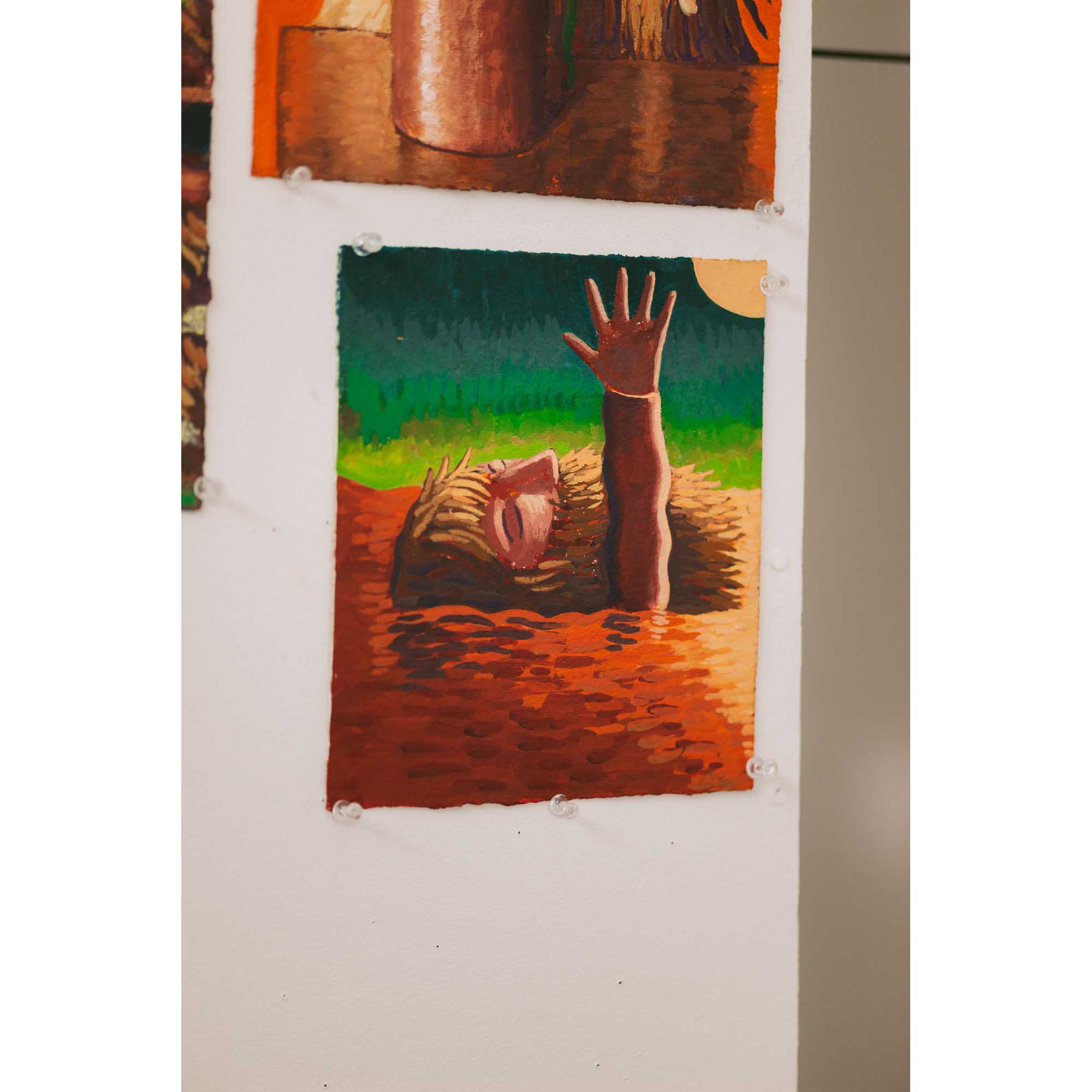

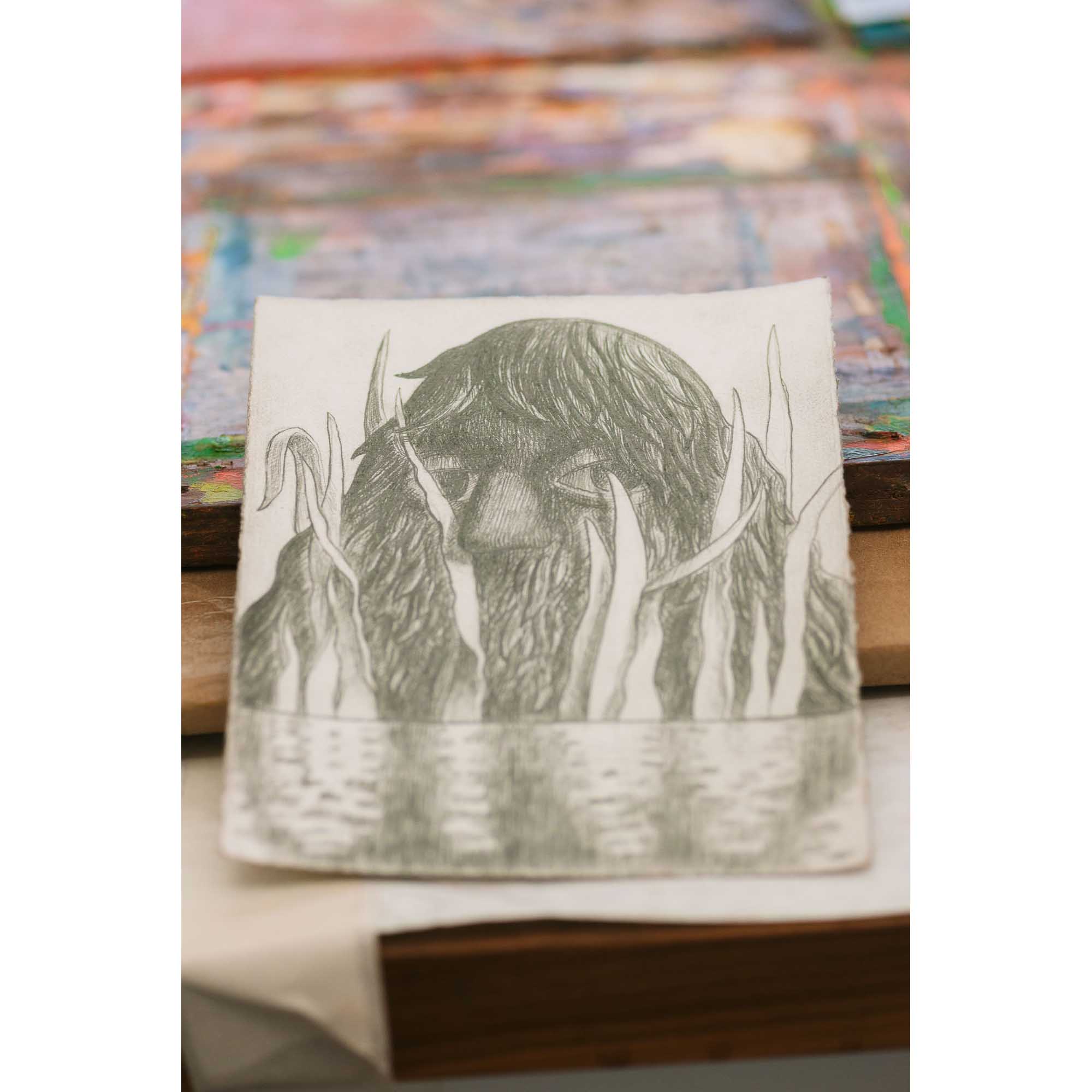

I think of them as gods and buffoons, male archetypes. I’m always trying to build up these statuesque figures and undermine them at the same time.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that you are statuesque.

Yes. [laughter] I’m interested in the vulnerability, the conflict, of what we want to believe about these figures—

Strength?

A father figure.

Sometimes a victim.

A passive character.

It’s a tragedy at times.

They’re sad, but kind of funny too.

Here you cut off the head, it’s laying on it’s side.

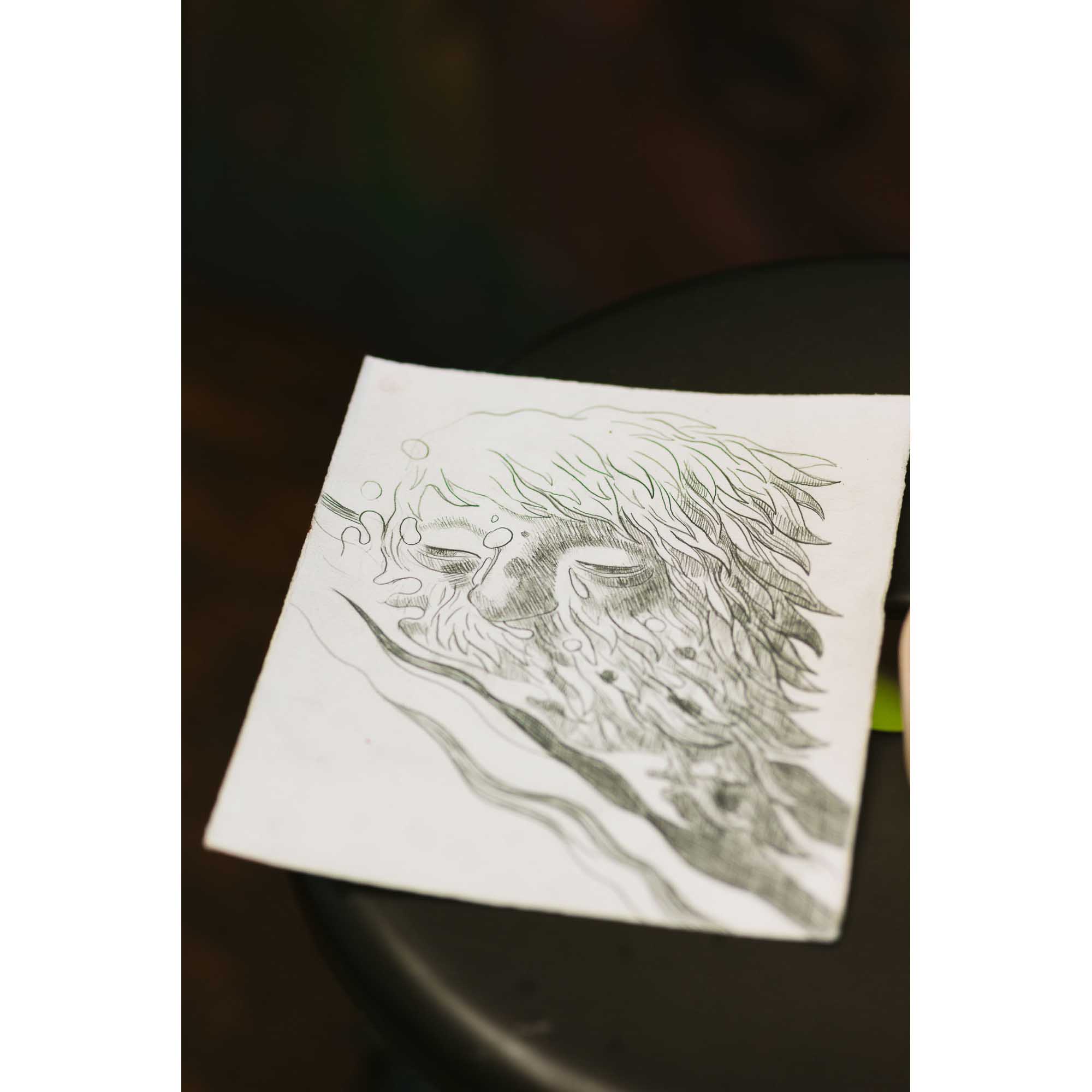

I build them up, and erase them then find them again

We’re talking about layering paint—

Layering paint—covering them up, scraping them away, obscuring them with things in front of their face, leaves, waves, shadows cast over. They’re victims of their environment. I think of them inwardly, in terms of my own life and my father; what I thought of him and who I thought he was. There was a print in my home, an Antonio Frasconi print of Walt Whitman, that I thought was my dad. My brothers and I all thought it was my dad because it looked just like him.

But it’s a print of a famous artwork?

There’s something in that experience that is totally related to my work. I think these things are fragile. As a father, myself, ideas about who I want to be for my kids, how you disappoint your kids as they get older, it’s unavoidable. I’ll never be the dad that I want to be. I’ll try. I’ll never be the dad they want me to be.

It’s crushing, isn’t it?

I think it is. I also think of the figures in a larger, outwardly way. How the world acknowledges the fallacy of our beliefs, the damaging part of our beliefs. How those things are laid bare, and the questioning. It’s the question and the crisis. I’m not trying to come up with answers.

You’re describing the transition from being a child looking at the print you thought was an image of your dad, to an adult having the question and the crisis of everything you thought to be true. It shifts quickly when you realize you have changed.

You see things as they are—

Maybe.

[Laughing] Maybe not. But it certainly changes.

And you realize how fragile perspective is.

It’s interesting, one of the things I went through was my dad having a really hard time for some of the choices he made. And that affected me. Part of the process was realizing he’s a flawed person. He’s not who I want him to be. We’re flawed things. [Laughing]

Flawed things. Back to the question and the crisis.

The crisis is that we find security in archetypal ideas that are attached to location or region and we elevate them. It has to do with being a man, there’s an agreed‑upon association that we can identify with and aspire to. But it’s not true.

It’s about the complexity around the value we put on archetypes.

And they’re dangerous. It’s like an identity crisis. And I’m not interested in answers, but I see it happening. In my work I ask, “How can I represent that? How can I build them up and question them at the same time?” It happens in process and in imagery. A lot of times these figures were crying. They’re not crying anymore. Well, some of them still are.

I saw one. What you described is the crisis of the male archetype that you had accepted?

Yes, that I believed in.

It can be applied to a broader scope, a crisis of your belief system, whether it’s about gender, religion, you name it.

Yeah, and as we grow—

Hopefully.

— hopefully, yes. You realize those things let you down. They’re not what you thought they were. That’s when I feel the figures are really buffoons. They’re having trouble, they’re passive victims.

When the figure is passive, the viewer can project their own story onto them. How did you get to the Pratt Institute?

I went to Pratt for graduate school. I was making allegorical still lifes. I feel they were more formal than they were conceptually interesting, I think. That’s just where I was. Then I started working with the figure again at the end of my time at Pratt. When I finished, I went to a residency called Skowhegan, in Maine, and I wanted to use those nine weeks to change the way I worked. I knew I had to change the way I made a painting. I knew that what I was interested in, what I responded to looking at other artists, but it wasn’t what I was doing in my own work.

What were you missing?

More inventiveness. Being less dependent on an image.

Using a photograph as a reference, for instance?

Yes. Kind of what I described with Bruegel—but I was seeing it in a contemporary sense. Another artist, Balthus, who is seen as a very problematic artist because he painted young women with whom he probably had relationships, but at the time his paintings personified an idea, that this, this world only exists here.

On the canvas?

This little stage only exists inside the painting. I had to be honest with myself, that how I was painting did not result in what I wanted my work to do. I had to start over. Two years and I just couldn’t figure it out. Then I had one break‑through painting that sent me in this direction. But I’d made work for a long time without much recognition. This is something I talk to students about. I feel like students get to graduate school, they get exposed, and they think they have to leave behind the thing that captivated their interest in the making; they have to abandon it. So, it becomes work. It becomes tedium.

They are trying to fulfill other people’s expectations.

And trying to make something that’s, quote, contemporary. In that, they lose the thing that kept them working. And so they stop.

They lose the internal reward? Do these paintings do it for you?

Oh, I find it in these paintings for sure. I can do this all day.

How did becoming a parent change your work?

My first son has a disability, he’s nonverbal, like Castle was nonverbal. Ryder can hear, but he can’t say words. At birth he was [labeled] “failure to thrive.” It was a difficult first year. I stopped making work. The stakes were so real; life or death. He couldn’t eat. We had to feed him with this little—it was a tube on our finger, and he would suck our finger. It was very hard for him to put on weight. We didn’t know that anything was wrong [physically.] We thought something was wrong with us. Going through something like that makes you more empathetic to other people’s struggles.

Absolutely yes.

When I started making work again, I stopped caring what people thought of the work. “How can I make work that’s about what I’m going through, that’s personal, that’s interesting to me?” I started making work I felt was close to me. Not thinking of the audience as much. I stopped going to openings. All those things you’re supposed to do to further your career. That’s where things changed for me as an artist. I was so self‑conscious before, like I had to figure out the right thing someone else would respond to, rather than figuring out what I might have to say.

Figuring out what you have to say is key.

And, then, when you talk about your work, it doesn’t sound—

Fake?

Yeah, it doesn’t sound like contrived. You mean what you say.

How freeing was that?

It was very good. Through that process you might stumble onto a unique voice and perspective because it’s based on your own experience. And that’s when people started paying attention to my work.

I feel like if we were doing a different kind of interview, we would narrow this down to a formula for success.

[Laughter] Yeah.

1. Have a life crisis.

Yeah.

2. Stop caring what people think.

Yeah, right, right. . .

3. Don’t look at other artists and compare yourself.

Yep.

4. Just put your head down and do the work. There, we did it.

Yes, that’s right. And hope people pay attention. You’ve got to be resilient, stick to your motivation, and have enough sense of self to prioritize who you are. The other part is to have enough conversations with the right people; there will be a couple that stick with you and inform you.

Inform you about your own work?

You won’t even realize that they’re important. Sometimes they are hard to hear. But you get little nuggets of advice that will pop into your head five, maybe ten years later.

When the time is right. What was that for you?

It was a studio visit, Alexi Worth, writer and artist, whom I sought out because I liked his work. He saw my work and instantly made a connection to American Regionalists. Which, today, there was just a big Grant Wood show at the Whitney. But that never would have happened back when I was in New York.

American Regionalism wasn’t trending then?

Not at all. It wasn’t popular, but I loved the work. Early to Mid‑Century, mid‑20th Century, Edward Hopper, Jacob Lawrence, George Bellows to a lesser extent. I loved these American artists but was embarrassed. I felt like I had to rid myself of that influence.

Because it wasn’t accepted in academia as a valid source of inspiration. Yet.

Yes. So, Alexi Worth made that connection instantly, and it crushed me.

You thought it was a bad thing?

It was something I was trying to get rid of in my work.

That’s so sad.

He said, “Why don’t you just make that your thing?” He talks about making your weakness your thing. For young artists, your perceived weakness is the thing you hold closest.

Not just artists. There’s a lot of psychology around weakness.

The weakness is the thing you feel the need to run away from. So, these manly, regional, somewhat biblical male figures that I liked to paint and liked looking at, why not run into that instead of run away from it? With my eyes open, be critical, be—

Be aware.

You can make it your thing and be critical at the same time. That was the best advice I ever got.

It was permission. What’s next for you?

It’s always just one painting at a time. My next show will be in New York at a great gallery. Then I have another show scheduled in London.

Congratulations. I’m thinking, people identify with work that leads with a true weakness over work that leads with a false strength.

I like that. People who are brave enough to be vulnerable through their work make work that is the most interesting.

West End

July 14, 2021

James Castle House Artist-In-Residence

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History. The views expressed in this publication are those of the individuals interviewed and do not necessarily reflect those of the City of Boise.