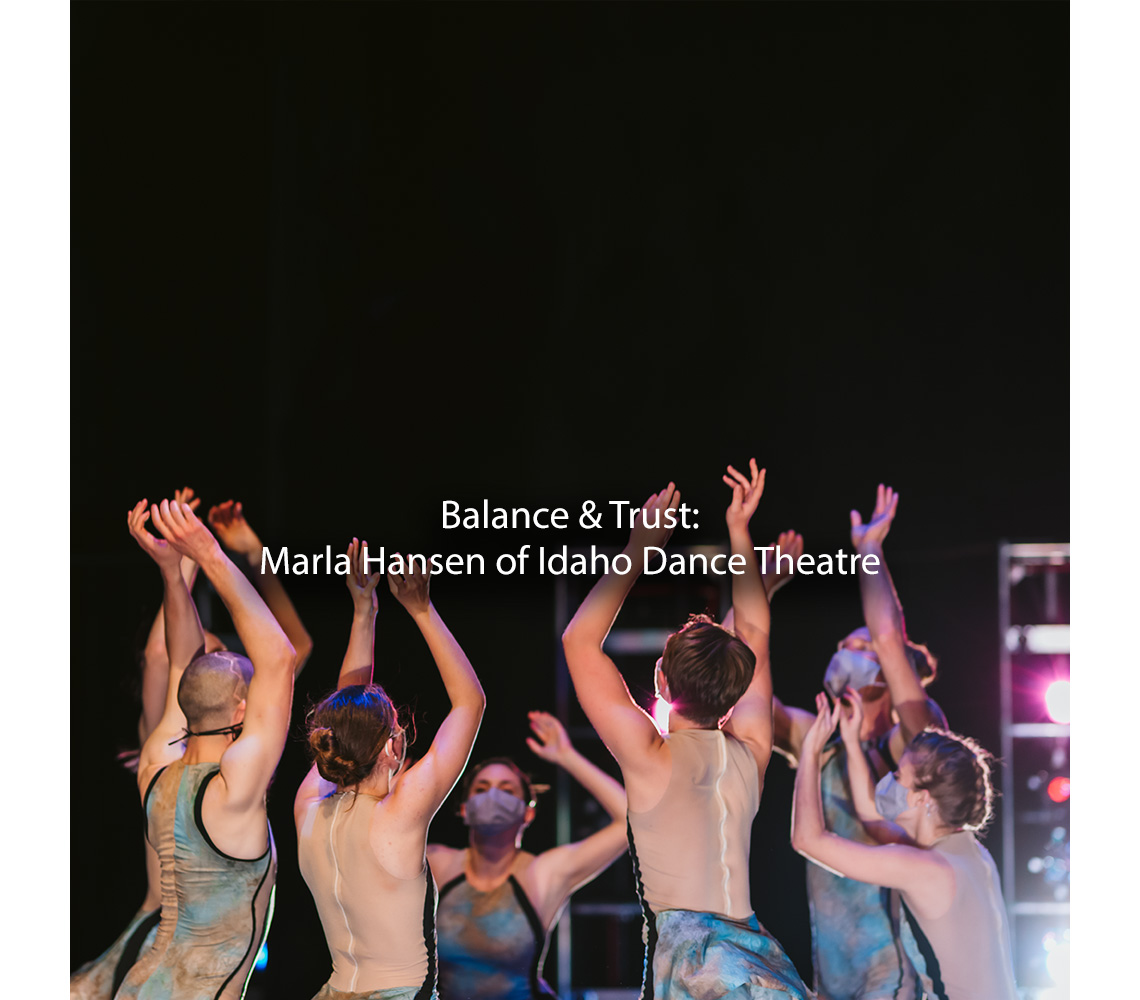

Creators, Makers, & Doers: Marla Hansen of Idaho Dance Theatre

Posted on 1/13/22 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History

Members of Idaho Dance Theatre collaborators and staff pictured: Anna Adaska, Lacey Bernhardt, Sophie Dalbratt, Kali Dey, Yurek Hansen, Alia Kelley, Meaghan Novoa, Lemuel Reagan, Evan Stevens, Connor Wentworth, Marla Hansen

Marla Hansen, Artistic Director of Idaho Dance Theatre, together with her husband Alfred Hansen, founded the company in 1989 when it took off with a momentum all its own. They acted as Co-Artistic Directors along with Carl Rowe until both men retired. Marla shares with us a memory of her sixth grade self, sitting in the corner of her dance teachers’ office, as they explained to her parents that she was something of a prodigy (our words, not Marla’s, if you ask her, she’ll be modest about it.) That was the turning point. Now, on the other side of the desk, she speaks about the complexities of a lifetime of dance from the physical demands on your body (don’t dance through the pain, and enjoy that adrenaline rush) to the emotional fortitude to keep things in balance. What kind of balance? Balance between self-criticism and self-acceptance, between your strengths and weaknesses, and between your personal and working relationships. What does Marla look for when auditioning dancers? Flexibility of mind and body, a collaborative spirit, and the ability to trust: trust yourself, your partner, your director, and the process. Most importantly, be nice to yourself and others.

What is Idaho Dance Theatre?

First of all, it’s a professional company.

Does that mean paid?

The dancers are paid, the choreographers are paid, the lighting techs are paid. All paid. We have a professional agreement with Boise State University, and have for approximately 30 years, as the professional company in residence that allows us to use the studio space here. For everything else, we’re on our own; marketing, grant writing, fund‑raising. It’s all our responsibility.

Are you self‑funded, then?

Yes. And right now those responsibilities fall to me because we currently do not have a managing director. We are searching for the right person. Also, IDT is a contemporary dance company, meaning we aren’t strictly doing classical story ballets; there are very few companies that do so anymore, only the very biggest companies. When I think of the word contemporary, it’s here and now, works are being made fresh. If we reset something, it’s not going back 100 or 75 years.

Do you have a favorite style?

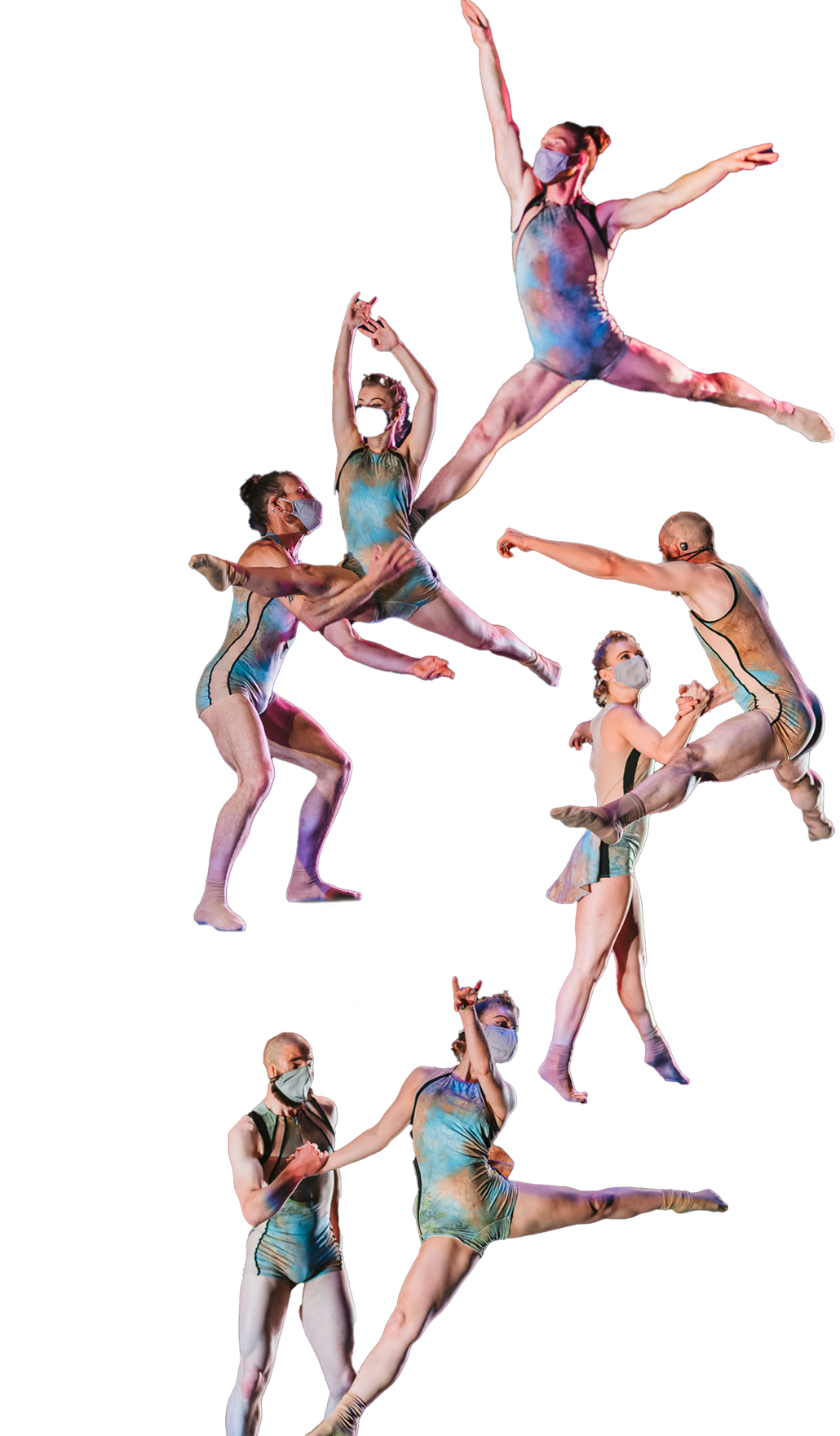

First, the style has to have strong technique. A lot of times, I don’t think my choreography is too terribly hard, but the dancers say, “Marla, this is really, really hard to do.” There’s high‑level ballet technique required in addition to strong floor work, and partnering work.

Technique comes first?

Yes and it’s physics, to be honest. Balance and counterbalance. For me personally, I love the challenge of working with a large variety of music. Different musical genres inspire different themes, qualities of movement. Sometimes it’s serious, sometimes it’s humorous, sometimes it’s completely abstract, and that abstraction becomes a through line, a theme you didn’t plan. I can’t say my favorite style, because it’s more about the creative process and making something new. That’s one of my favorite things about doing choreography, it’s not predictable.

How did IDT start?

That’s an interesting story. My husband and I, Alfred Hansen, danced with American Festival Ballet for nine years, originally based in Moscow, Idaho. In the spring of 1982, they moved the whole company to Boise. They changed the name to Ballet Idaho, later, in 1992, I think. But I became the acting artistic director when the man they’d hired to do the job changed his mind. He was supposed to set a full‑length Cinderella. So they asked me if I would choreograph the full‑length Cinderella. This was about 1988.

When you say he changed his mind, what does that mean?

When you say he changed his mind, what does that mean?

It means—he had a company he was directing back East, and American Festival Ballet offered him a contract, to which he said yes. Then apparently—I don’t know why, and I’m not going to speculate why—but in the middle of June, when he was set to start his position in July, he said, “No, I’ve changed my mind.” At the time Esther Simplot, who is and was heavily involved with the board, approached me about taking on the role.

That’s quite the offer.

It was. I was primarily a dancer and ballet mistress, so—

Oh, what’s a ballet mistress?

The person who teaches company class. And helping the artistic director gives notes and corrections.

It’s a leadership role.

Yes. So to take on more made for a lot of hats to wear; I was also still being cast as a dancer. But that year I said yes to choreographing the full‑length Cinderella; I thought, “I have nothing to lose, okay, I’ll do it.” It turned out fabulous. Alfred was one of the ugly step sisters and Carl Rowe was the other ugly stepsister.

I can see that. (Laughter)

We took it on tour, all over the West, clear down to Arizona, up to Montana. While on tour, the company, the board, did end up getting a guy to come on as the full‑time artistic director. They wanted an outsider.

Yes.

And I think they wanted a man. They also wanted someone with an outside reputation.

That’s common in the arts, to search out who you believe will bring a fresh perspective. And of course the glass ceiling thing. Hopefully that’s beginning to change.

Yes, typically. The very last show of the tour he showed up at the theater, down in Arizona somewhere. So I thought, “I guess I’m done.” He turned out not to be a very nice person and at the end of the season, almost three‑quarters of the dancers quit.

Over half the dancers quit?!

Including Alfred and myself. There was a huge transition.

There’s a silver lining somewhere I hope?

We got a phone call from the Wyoming Arts Council; they wanted us to come do another show.

They called you directly?

They called me directly. They assumed I was still the artistic director. I said, “Well, we’re not with the company anymore.” They said, “Do you want to come anyway?”

Yay!

We literally pulled together a pickup company of dancers who had also quit and put on a whole performance with new work, reset a couple things, and did the show.

That’s very gratifying.

When we got back, people in Boise said, “You should do the show here.”

I think I see where this is going. (Laugher)

We did the show in the SPEC [Boise State Special Events Center] and, “That was fun; let’s do it again.” We got ourselves a board of directors and nonprofit status, and just kept going. That was 1992.

Congratulations. What an interesting start!

It wasn’t planned.

But it had its own momentum.

We kept getting asked to do more work. Getting bookings.

Invitations—

People wanted to know the name of the company; well, I don’t know! I talked to my brother, a journalist, and he said “Okay, now, what is it you do? Where are you? Do you perform in a theater? What kind of work do you do?” I said, “We dance. We’re in Idaho, yeah, we do it in a theater.” “How about Idaho Dance Theatre?” he says.

Of course!

And it worked.

You and Alfred took on leadership in the beginning, today your son Yurek Hansen is a company dancer. Would you say IDT’s a family thing?

It’s been hugely that way, but it’s also been a family of many families. We’ve got dancers who started with us years ago, and their students are now auditioning for the company. We’ve gone through a lot of phases, financially, structurally. Carl Rowe was commuting to and from Sun Valley—choreographing and performing; the three of us were co‑artistic directors. He got tired of commuting and moved here where he ended up falling in love with his, now, wife, Tracy.

You, Fred, and Carl worked very closely together?

For many, many, many, years, yeah. Fred got to the point where he could no longer dance safely. He had pushed himself as far as he could so he went into lighting design and was very successful at it. He retired from that a couple years ago.

You also stopped dancing at some point?

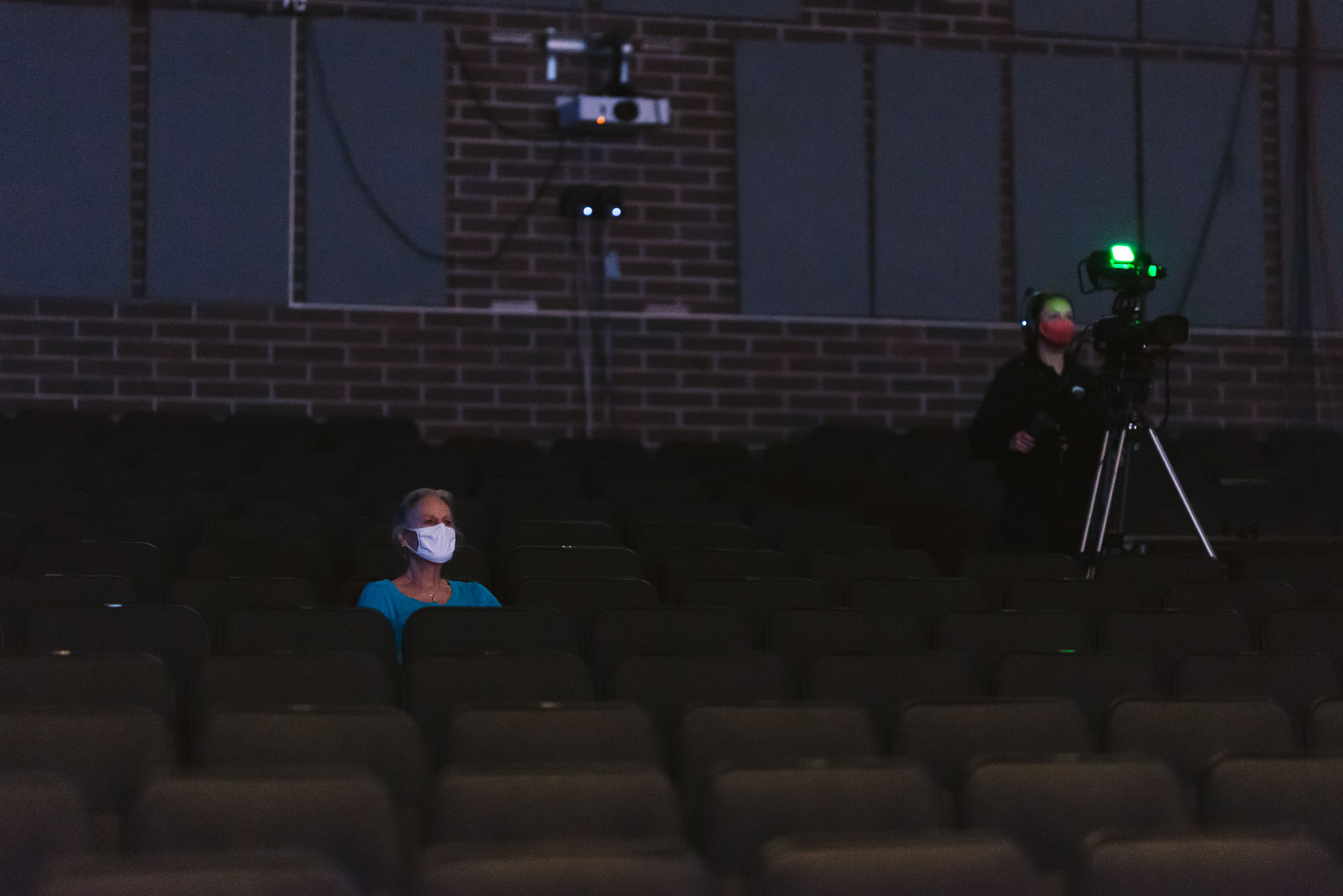

When I went from no longer dancing to general teaching I felt, physically, like I had no adrenaline, I’d kind of died inside. As a dancer, your body gets used to the rush of adrenaline from performing. It was like getting off a drug. That dead feeling slowly started to go away and I got a new sense of adrenaline from the audience response as a choreographer and director. I wasn’t relying on being a performer to get that physical sensation.

That’s a hard reality of an athletic career.

When the rush was gone, it took a while, but it came back in a different form. I get a sense of exhilaration and pleasure from watching the works I choreograph, and from coaching people. I don’t have to be the one on stage anymore to get a great feeling about it. But for some dancers, they can’t return to the theater as an audience member, it’s too painful.

Yes, the emotional tie. That’s a huge deal when you are used to dancing every single day. Let’s talk about the physical demands. What would you say to young dancers just starting out?

This is something we stress here in our classes: know your body. Know about your joint structure, your muscles, how to properly warm up, how to do physical therapy. If you’ve got an injury, even something small, figure it out; don’t just dance through it. Learn why it happened, what should you do to prevent it from happening again, and how to heal.

Take care of yourself?

Dancers can perform a long time if they are training properly and using correct technique. It’s just like any athletic activity, you have to learn the proper technique.

Had you been told in your career to “dance through it”?

Had you been told in your career to “dance through it”?

Oh, yeah. And many times I shouldn’t have. Having been a dancer, myself, I really get on dancers’ cases, “Okay, you’re rolling in, you’re not holding your knees over your toes…”

You’re watching out for their body as well?

Constantly. Every good teacher does. I mean, there’s more emphasis on proper training and proper eating today than there was. But there have been, like, New York City Ballet dancers, who ended up in a wheelchair or using walkers because of osteoporosis.

Oh that’s crushing.

And there are still issues with weighing dancers, because they are looking for a body type. But how much someone weighs is not an indication of how they look.

Are there ways IDT has challenged those ideas?

I would say we’ve really made some differences. And I think we’ve affected other dancers and companies too. We have dancers who are very tiny and some who are very tall, in terms of women. Anna Adaska is 6‑1, and a very long, flexible, beautiful dancer. When she auditioned she told me too many companies had said, “You’re too tall.”

She was rejected?

Yes. But when she auditioned, and I watched her move, “You know what? I can’t wait to work with you because you’re going to bring a whole different look and a new physicality, things that I can do with you.”

YES!

We’ve had dancers with a different silhouette than what’s typical. To me, the most important thing is: are they nice to be around?

How many hours do you work together?

Every week, when we’re in rehearsal, it’s anywhere between 20 and 25 hours a week.

That’s a lot. And year after year as well?

Oh, year after year after year, yeah. Ultimately, the ones who don’t stick with it are the ones who are so darn self‑critical; they degrade themselves, or they can never live up to their own expectations, or what they thought someone else expected. I’ve known fabulous dancers who quit. But the ones who stick with it figure out how to deal with the pressure and how to accept themselves and work with what they’ve got.

There’s no such thing as perfection?

Absolutely not.

With something as technical as dance, you can visualize an ideal in your mind, but how do you tell yourself it’s okay to not reach that ideal?

You have to find your strengths and really work those, and your weak areas? Build them up. Some people have very good jumps because they have that kind of strength required, while other people are very loosey‑goosey, and can’t do very good fast petite allegro, quick jumps with beats and things like that because they’re too free. So you have to learn to make your body capable of doing it all, the best you can. Which is where it comes back down to training. And ideally, you aren’t being chastised in the studio to the point where you give up.

You mean by a teacher? That chastisement is in detriment to the person?

I’ve seen some terrible situations. It’s been interesting because with social media, you’re hearing a whole lot more about negative situations. So there are good changes coming.

How did you become a dancer?

Both my parents loved music and my dad actually took some ballet classes. He was a football player at Oregon State University.

Did he take dance for football?

He took dance for football. He and my mom were both very involved in the arts and loved music from all over the world. He was an Air Force pilot, so we traveled a lot; I was exposed to a lot of varieties of music. Whenever they put music on I’d dance around the house, so it was, “Let’s put her in ballet classes.” I was probably six. And I loved it.

You were happy to do it?

My parents never tried to tell me what to be or say what I should do. When we lived at the Air Force base in California, there was a studio nearby, and my folks watched a class and came out and said, “They’re not doing good training. We’re not going to have you take classes here.” For two years I didn’t get any ballet.

It didn’t pass muster. Mustard? [Laughter]

It didn’t pass. They knew enough about good training and they did not want me in a program that was poor.

They didn’t want you to develop bad habit?

Exactly. Later we moved to Montgomery, Alabama; there was a very good studio there. This was probably the turning point; I was given the opportunity to do a pointe solo in the big recital. My mom made the tutu for me.

What age?

I was sixth grade. After the recital, the directors, a husband and wife team, asked to meet with my parents. I remember sitting in the corner of their office, they said, “Your daughter has the right physicality, the strength, the musicality, and the performance quality to be a professional dancer—

Wow!

—if she wants to.” They encouraged my folks to let me pursue it, they said, “She can do this if you help her.”

They saw your aptitude and potential?

They did. The fact that they took the time to say it and for my folks to hear it made a huge difference. Because of their support—I don’t know if I would have been gung-ho to go this path. I always thought I was going to be a forest ranger or something because I love the outdoors, and we camped all the time.

You probably wouldn’t have met Fred in the woods. Did you two meet in a dance studio?

Yes, at University of Utah. He was a modern major. I was a ballet major. It was very romantic.

Mmm-hmmm.

He lived in a house with a whole bunch of guys. Not a fraternity.

Just a house full of guys?

A house full of guys. There was Fred Davis and Fred Hansen, and both dancers. Then there was Jim Stoy and Jim Davis, both biology majors.

Jims and Freds?

Jims and Freds. I got to know the Freds because they were modern majors; because I did a lot of choreography I was always looking for dancers. I ended up casting Fred in some of my choreography.

Which Fred?

Hansen.

Oh, yeah, obviously.

We got to know each other better and better and started hanging out, so. . .

How good was the chemistry when you danced together?

Oh, it was great.

…

While Fred was in a company in San Francisco, I took a semester off to be with him and we got hired to do a tour, Sugar Plum and Cavalier. Now, back in those days, if you weren’t married you were not supposed to be sharing a motel room. We got married so we could stay together on the tour. That was our logic.

While Fred was in a company in San Francisco, I took a semester off to be with him and we got hired to do a tour, Sugar Plum and Cavalier. Now, back in those days, if you weren’t married you were not supposed to be sharing a motel room. We got married so we could stay together on the tour. That was our logic.

It’s more practical to pay for one room than to pay for two. My grandpa—rest in peace—always said it’s cheaper to live as two than to live as one.

It’s more practical to pay for one room than to pay for two. My grandpa—rest in peace—always said it’s cheaper to live as two than to live as one.

The fact that we could dance together and present pas de deux, plus teach modern, pointe, jazz, and men’s classes; we could teach anything between the two of us. We really got a lot of work as a couple.

Living and working together, that can be good but also a challenge.

It was very good. But here were times—I remember some rehearsals, and times where maybe, with my choreography, I was asking Fred to do something either very difficult or uncomfortable. Times when I just had to hold back. You’re a couple, you know, you can get some antagonism going, and you have to draw a line between your working relationship and your loving relationship; not let it get mushed into a mess, which some couples can’t do. But we did and were able to keep our love alive. Even if we didn’t always agree about the rehearsal process.

I can imagine how uncomfortable that could be.

Rehearsals can be very stressful, especially in partnering situations where one person is maybe resistant or not trusting.

You said earlier the number one requirement for your dancers is they have to be nice to be around. How can you recognize in an audition whether that will be the case?

Not only do I watch them dance, but I ask them to do some improvisation with company members. That is usually a good way to tell how they might react with each other. Then I always have the conversation about, “What are your goals? What is it you really want out of your dance career?” I try to make it very clear that we are not a 40‑hour‑a‑week company. We don’t have that kind of money. You’ll have to get another job on top of this.

You see if they can be matched with what you can provide?

And how willing are they to try new things and work with a variety of choreographers and a variety of musical styles, are they going to get stuck in their ways?

Are they resistant to change or collaboration?

Something super important to me, that I’ve really tried to nurture, is the studio environment. When somebody is giving a correction or asking for a change, the tone of voice, the choice of words is important. And that dancers do not think of it as a personal affront. It’s all about the work. It’s about what we’re creating. It’s not about you as a person.

Don’t take it personally. Learn, grow, repeat.

The best dancers are the ones we can work with over and over and over. Sometimes I step in, because I hear things, I will pull dancers aside to say, “You’ve got to figure out how to say what you’re saying in a different way.”

Because it’s not landing right, it’s breaking down communication lines instead of opening them?

And you don’t want people to get defensive.

In any performing art, ego comes into play.

Well, that’s for anything.

Yes, and performing arts are especially known for ego.

It can be detrimental. But sometimes you have to have it, or you won’t be able to get out there and do what you have to do.

Yes, it’s scary to put yourself out there for an audience, or for the audition process. Your ego must be strong enough to withstand rejection and the embarrassment of making mistakes in front of others.

It’s terrifying. [Laughter]

What do you see in the future, for Idaho Dance Theatre?

I envision that two, maybe even three people will take on the role of co-artistic directors, when I pass the reins. We’ve got very talented choreographers, even dancers, who are good with managerial skills.

What is a challenge you face?

The hardest thing right now is that we need a full-time managing director, and to raise the funds for that. It’s a difficult time to feel confident in keeping that person employed.

Who should people call if they want to donate large sums of money? [Laughter]

Tell them to call me. You know, my goal is that, you have to be willing to change your vision, be flexible. The other thing I’m constantly trying to do is trust.

Great advice, both physical and emotional.

Downtown

January 12, 2022

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History. The views expressed in this publication are those of the individuals interviewed and do not necessarily reflect those of the City of Boise.