Creators, Makers, & Doers: Emily Culver

Posted on 7/27/22 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History

Emily Culver, multimedia object maker, problem solver, and Artist-In-Residence at the James Castle House shares with us her work in progress and how she wants to form a bridge between objecthood and the body. We asked a lot of questions and Emily delivered. We asked: What is OOO? What’s your favorite color, food, hierarchy? Why are we uncomfortable with our own biology? Why metalsmithing and not painting? In examining her work, a lot of borderline taboo words came up, starting with the letters “P” and “V”. Read more to see what we left uncensored, what Emily aims to teach her students at Old Dominion University, in Norfolk, Virginia (congrats on the new position, btw!) and read the question that stumped her. We could just tell you, but it’s better if . . .

I’ve gotten a good look at your work in progress, matter of fact I’ve touched pretty much everything, and I’m excited because, as for our conversation, each question takes us deeper into your work and into terminology that’s new and exciting for me—BUT, for our readers, let’s start with: how do you describe your work?

I’ve gotten a good look at your work in progress, matter of fact I’ve touched pretty much everything, and I’m excited because, as for our conversation, each question takes us deeper into your work and into terminology that’s new and exciting for me—BUT, for our readers, let’s start with: how do you describe your work?

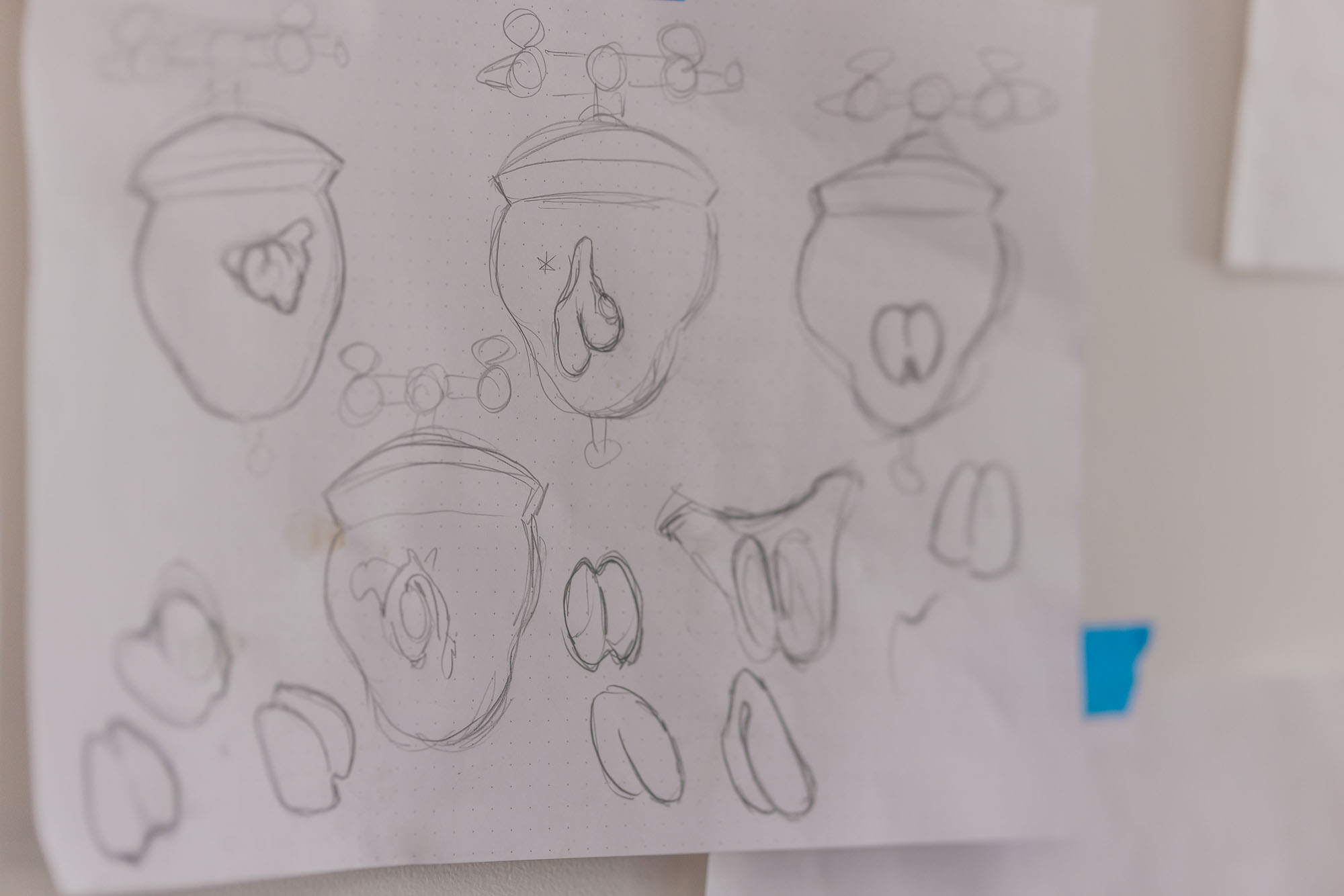

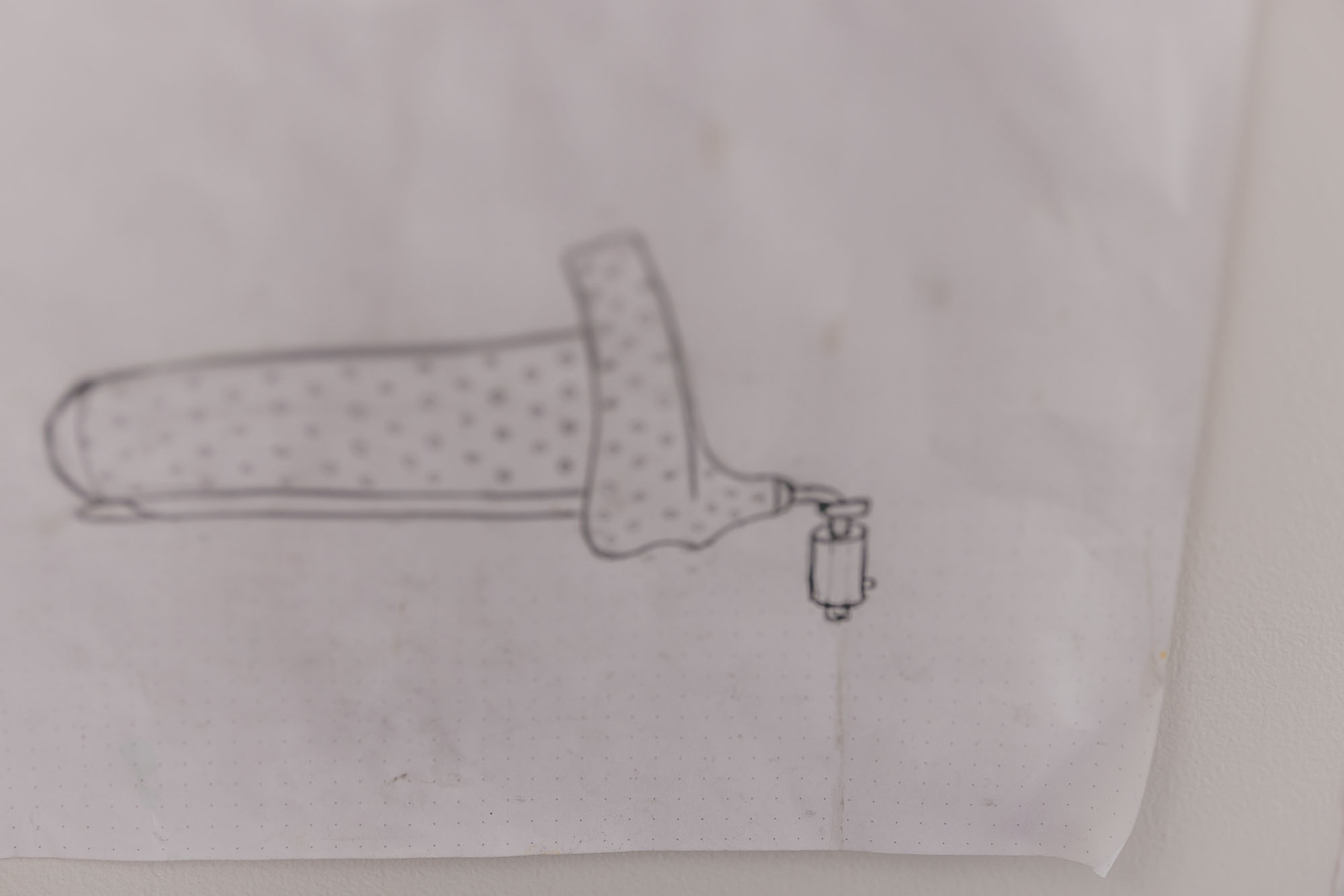

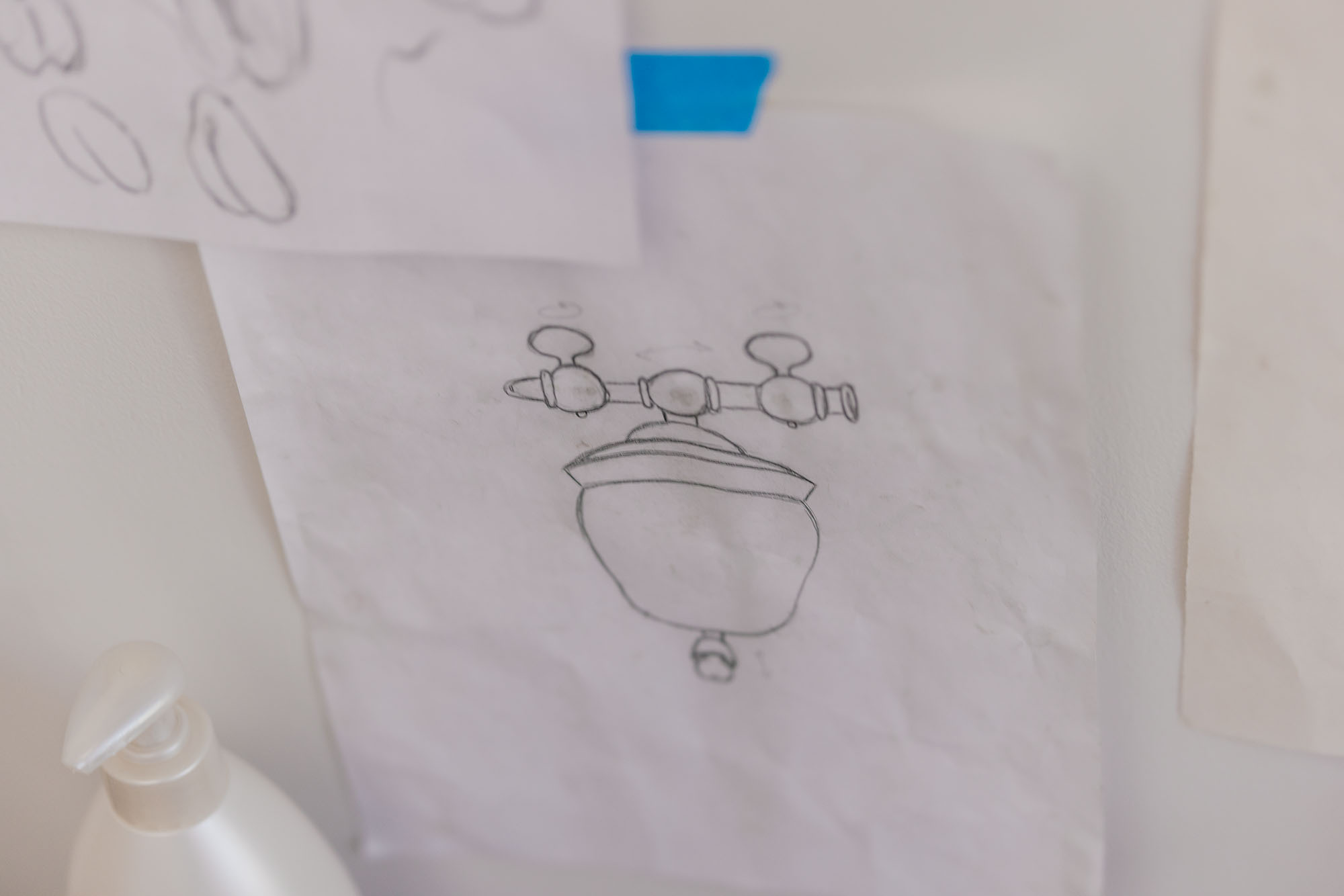

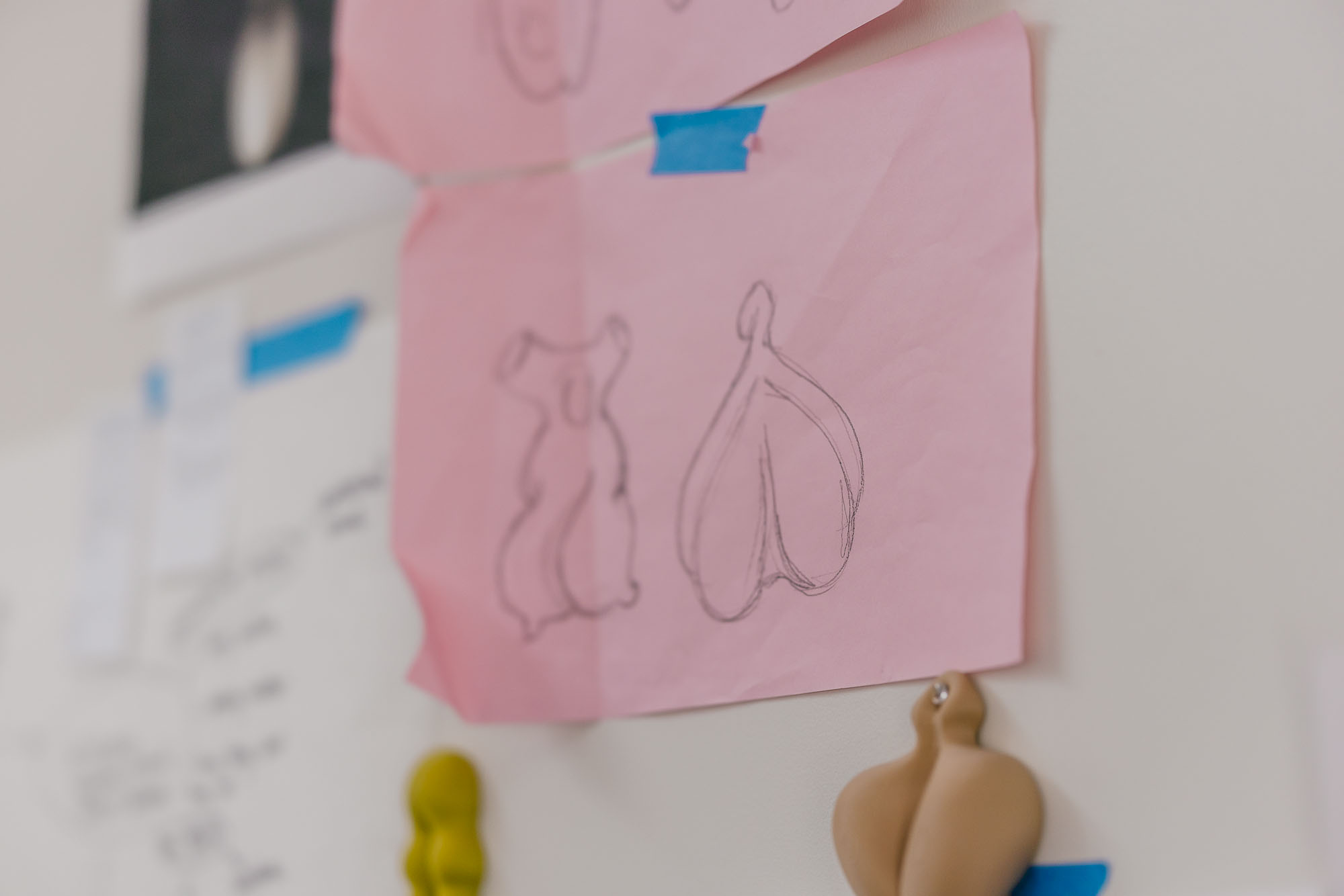

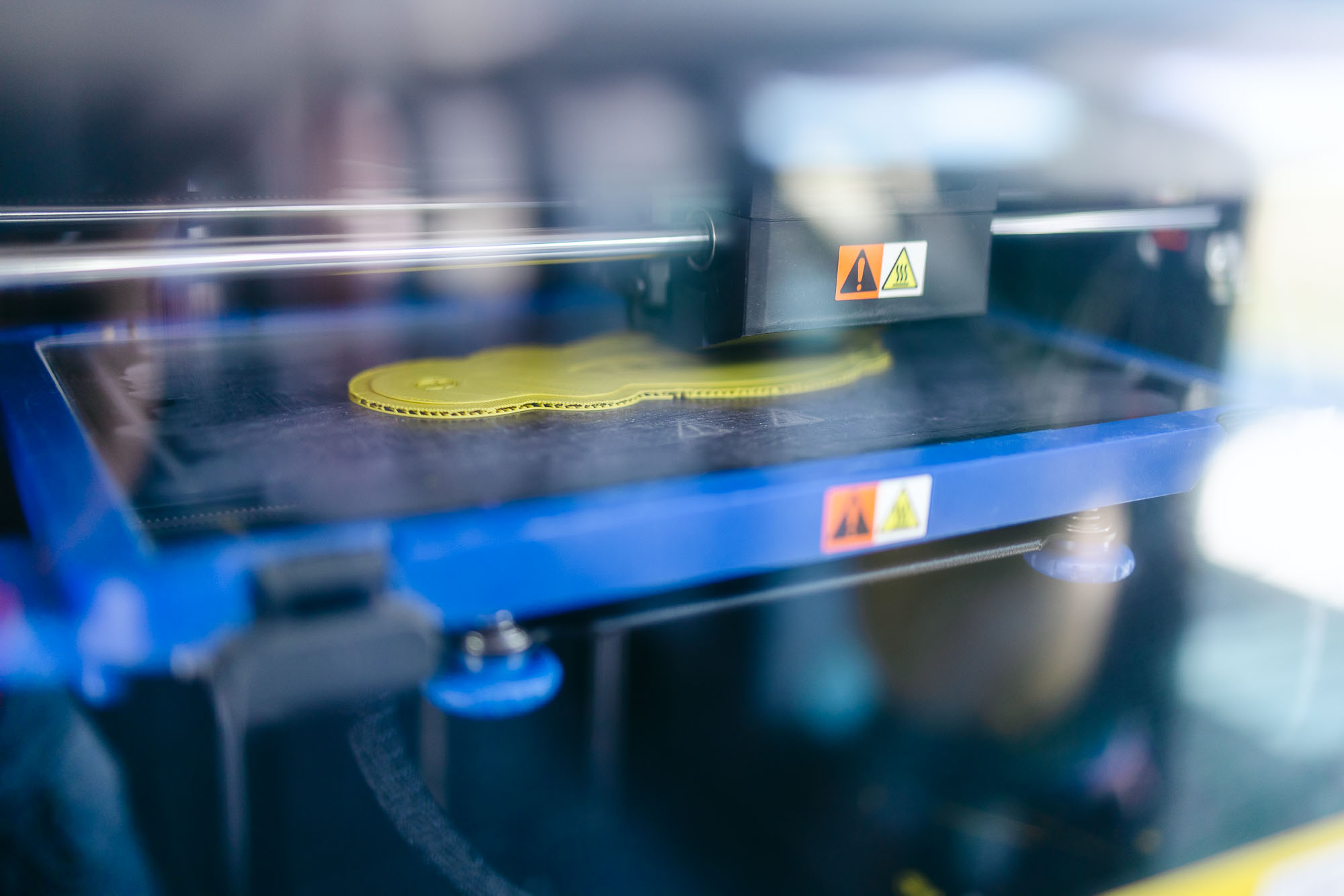

I call myself an object maker. My education and training is in jewelry, metalsmithing, and computer‑aided design. The idea and concepts surrounding objects are what I find most fascinating, whether it’s materials, scale, suggestion of functionality and purpose—those are the kinds of things I like to investigate. While they’re made of metal, wood, or stone, the work circles back to a question, “What is this thing, what is it for, and how do I use it?” and more specifically “How does it relate to my body?”

That’s a very good summary.

I’m trying to form a bridge between the the idea of objecthood and the body; objects that engage with the body, or objects that become bodies in their qualities, or how they interact in space and with other objects, as though they’re autonomous entities.

Because we’ve already been talking for an hour we’re kind of deep into this—I’m going to pose a question: body versus object. This is a little theoretical, but, as a human being, why do you think we see a separation between body and object?

I think it comes from the fact that we live our experiences through our bodies, which is an object, which is an inescapable prison. It’s the only way we can understand things: we look, we interpret, we feel.

Through our senses.

I understand myself as my own entity, I see you there as a separate entity. Same thing with, for instance, this mug. I would draw a distinction between you sitting there, moving and interacting, and this mug, which feels inanimate. There are some really curious philosophies, one in particular, Object‑Oriented Ontology, which breaks down our hierarchal understanding of this relationship, and instead, places things on an even playing field.

Say that again

Object‑Oriented Ontology, OOO.

Let’s Google it. Okay, Wikipedia says OOO “is a 21st-century Heidegger-influenced school of thought that rejects the privileging of human existence over the existence of nonhuman objects.” It’s German. I’m guessing that, because I am alive, I place living objects at the top of my perceived hierarchy. A mug is inanimate. I don’t want to be a mug because to be a mug means I’m inanimate and to be inanimate means I’m dead and I don’t want to be dead. I want to be alive. That’s very important to me.

On the flip side, rather than seeing it as reducing yourself to a [lower] level, why not instead bring everything up?

Okay…

We’re very anthropocentric‑focused, right? It’s all about us.

Yes…

Yes…

For the longest time we thought that the sun circled around the Earth, for example. I think it’s far more interesting to look outside ourselves to explore and open up to the vastness of existence. There are things we are not going to completely understand. For me that strikes such an imaginative spark, I always want to linger there. In order to be in that space, I have to put myself to the side.

How do you put yourself to the side?

It’s related to how I would describe Object‑Oriented Ontology: We have a tendency as individuals to do what’s called overmine or undermine objects. We either reduce them to the scientific: everything is made up of atoms, molecules. That’s undermining.

That the meaning of an objects equals it’s physicality.

Or we have a tendency to overmine. We place large theoretical, religious, or spiritual importance on an object. OOO argues there is an in‑between where the object actually exists. But we can never fully access it because we always undermine or over mine.

Isn’t that what it is to be human?

Isn’t that what it is to be human?

Yes.

To make meaning.

Or—

Or make meaning as a way to create and claim power.

For OOO, everything exists on an even playing field. There are imperceivable relationships and communication happening between ourselves and objects.

All the time?

Isn’t that so fascinating? It opens up your world; things happening behind a veil that you or I can’t fully understand.

Yes. Looking around this room, now, I’m all freaked out.

Not to mention there are concepts like the hyperobject. Timothy Morton writes a lot about hyperobjects—things that are vast and complex. For example gender is a hyperobject. The pandemic is a hyperobject. Global warming is a hyperobject.

This is my perfect Ted Talk, right here.

[Laughing]

We’re going to have come back to hyperobjects. Let’s go back to your work. Here are my first impressions: they are small objects, palm‑sized. Some are 3D printed, some have a white plaster-like coating. And when I walked in, I immediately said “That one is phallic; that one is vaginal.” [laughter]

Right.

Are they always this size?

No, I’ve made some that become like furniture in space. But things of a handheld nature attract me. There is a longing for engagement; it beckons and calls to the viewer in a way that other [sized] things do not. Even in a museum or a gallery, people walk up and and touch my work.

That’s the first thing I asked, “Can I touch it?”

Yeah.

Which made me question myself, why do I want to hold this phallic thing—it’s like a, a banana.

Right.

It could just mean I’m attracted to bananas. I’m wondering how much we’re going to have to censor this interview. [Laughter]

I also see some of the work like a void, you gaze into it; it’s almost like entering a dark room, you can’t see anything, then as your eyes adjust, you start to speculate that you see things. Or like gazing into a mirror. When you look at the objects l make, you notice more about yourself than about the object.

Why did you relate your work to looking in a mirror?

Because it reflects ourselves back at us, a self‑acknowledgment. You look at it, there is maybe a suggestion of something; you, through considering the object, take [the suggestion] further.

I am filling in the void from my conscious or subconscious. So the suggestion I personally bring to the work is that it’s, ahem, a banana. And I want to hold the banana. I question, does it say something about my sexuality? Then I feel uncomfortable because of the topic, the Taboo, perhaps. And that Taboo rests inside my own perspective.

You recognize yourself through experiencing the piece and in a way that takes it much further than what’s actually sitting on the table.

I don’t know, Emily, it’s pretty phallic. [laughter] What stands out to me is that I have to face the fact that I’m uncomfortable with my own biology and the topic of sexuality. Why am I uncomfortable with my own biology? That’s a good question isn’t it?

Our biology should be the thing we’re most familiar and most intimate—you live it every day.

I poop, I pee.

You experience pleasure, you experience pain, you experience all these things, but—

I’m not ready for this today.

I know. But it’s so perplexing to me.

It is.

It’s all tied to our physical selves, lived through our bodies. Somehow we can’t deal with it.

Maybe you could write a book and I can read it.

I would love to, but I don’t think—that seems a crazy feat.

How about we just do a really long interview? Earlier we started talking about the very basic human experience of touch, like how a baby’s instinct is to put everything into their mouth. Then we jumped to OOO, a philosophy that asks you to put yourself to the side and “reject the privilege of human experience over the existence of nonhuman objects.” And here we arrive at gender versus biology and my comfort level. There was a question in there somewhere.

There’s many steps to understanding something. When I work, I am looking at the poetry of the form, the suggestion of the material. There’s always that initial entry point, even if you never think about those other philosophies.

Form and material.

From there, the work goes a bit deeper and even deeper. When you put things together in the space it becomes a larger understanding. I think the work can be accessed on many different levels.

I do too. Are people repulsed?

I think actually the opposite. People are drawn to it.

But do some people make a wide arc around your work, to get to, say, a safer painting?

Perhaps, but I like to think there are certain inescapable allures. The seduction of material, or, thinking about the capabilities of metal, to be pristine and shiny and—fetishized; color, texture. There’s a richness in the materiality—you know, you walk down the sidewalk and see something on the ground, a thing you can’t quite recognize is the thing you spend a long time looking at. It makes us pause because we want to understand, we want to recognize—

Make meaning.

But there has to be enough there to feed you.

There has to be enough semblance available to the viewer to be engaged.

Or, another allure is jewelry—

Oh, it’s accessible because—

—people understand that jewelry is meant to be put on the body. Even if it doesn’t look like any jewelry you’ve ever encountered; if I were to hand you the little plastic pull from my milk container lid—If it fits your finger, and I tell you it’s a piece of jewelry, you’re going to take that plastic tab and you’re going to put it on your finger.

I tell my art students you want art to be like an unfinished… so that the viewer can complete the work.

I tell my students the same thing. The most profound experiences I’ve had with work are when I feel as though I come to a space on my own. When I make work, I try to leave bread crumbs, because if I were to tell you something—

—if you tell, don’t show; it’s going to annoy me.

Exactly. But if you feel like you live it yourself, you have ownership over that experience, and therefore it’s yours.

Do you have pet peeves when it comes to art?

Like outside of my own work?

Sure.

Pet peeves.

You’re allowed to be petty.

I don’t know, I guess—things that feel like one‑liners or—that’s a good question. A pet peeve. I would have to boil it down to genre‑specific.

Okay, let’s go there.

I don’t know if I can answer that question. Let me think on that.

You think on that. Your spouse is also an artist? Are you two a compliment or a contrast?

We overlap but there are definitely some big differences. That’s reflected in the way we work. We both have very high standards, we’re both very particular; I’m probably even more extreme. I don’t know if busy body is the right word; I always have the new thing I want to try. Whether it’s pickling vegetables or learning how to sew or—and that really comes through in my work, because everything is a one‑off; I’m always learning a new process or having to solve a new problem. I think Kyle experiments as well, but I feel he’s able to return to things that are in a wheelhouse more I am.

You’re not interested in repeating the same thing over and over again?

I get frustrated with myself because I spend a lot of time problem‑solving and experimenting, but I don’t continue to reap the benefits of that labor.

Follow‑through?

I do follow through for that one piece. I could make more work if I made more work that was similar. Does that make sense? There’s a lot of time, labor and energy that goes into trying to figure out a new language. And I do that over and over and over and over.

You don’t stand still long enough for the rock to grow a bunch of moss that could be called a body of work?

When you look at the aspects of being an artist—gallery representation, or being able to turn out solo show after solo show every year—

To build a brand.

If I just made it easier on myself. [laughter]

Oh, the easy way? [laughter]

I’m not actually interested in the easy way. I kind of coined a phrase here: “I’m not really an artist, I am a problem‑maker”

[Laughing]

“And then a problem‑solver.”

Fabulous. Why the body?

I think it’s this inescapable thing.

I agree. But I am also an artist and I’m not making work about the body.

I really only came to these realizations later, but, my mom is in the medical profession. She was a midwife.

Have you watched a live birth?

No. I have seen videos. At her work, I would go into areas of the hospital—I would go in the—what’s it called? Like the—

The morgue?

No.

Darn.

No. Back‑rooms with diagrams and anatomical models. My two sisters are in the nursing profession; I sit around the dining room table while they have conversations I can’t follow—

They’re talking industry.

They’re speaking this whole other language I’m not privy to. I thought I wanted to be a painter, but I got really frustrated with the image. I started cutting the canvas, and I wanted to consider the back side.

“Why isn’t anybody paying attention to back of the canvas?”

Yeah, so I took a jewelry course and I was hooked. There is so much to learn, it’s challenging, it’s difficult. Besides laborious, there is also a high possibility of failure.

Why?

At any moment something can go wrong, the obvious thing is that if you overheat your piece, it melts.

It doesn’t set you back just one step, it sets you back to—

—the very beginning. It’s high‑risk. Also, the field is so vast—oh, my God, it’s huge. You have to consider metal—

The whole history of how our use of metals has evolved—

—and jewelry, which is not always made of metal. And there’s the conflicted relationship between material and subject matter. Let’s just talk metal jewelry making: casting—but within casting is: cuttlefish casting, vacuum casting, centrifugal casting, pouring ingots, sand casting—okay?

And within each of those are the various cultural histories—

—and enameling: champleve, cloisonne, plique‑a‑jour—

You’re going to have to spell all of those.

Metal fabrication: forming, raising, sinking, hollow form fabrication. I mean—

It does make brush to canvas look very simple. Sorry painters.

—cold connections, tap and die, rivets, hinges, box clasps. It feels like an ever‑expanding, complex field for me to play in. It’s very exciting. I feel that the physical encompasses all the qualities of the image and more.

I had a feeling you were going to say that. How?

If we’re talking composition, color, line, arrangement, then—like, throw in gravity.

Oh yeah that’s good. I wish I were a sculptor. [laugher] What scares you?

As much as the subject of failure is part of my work, failure scares me. It’s something about falling short. There’s wanting and, then, there’s desire, but desire is never fulfilled, it’s just there. There’s also rejection.

Ew. [laughter] Let’s talk favorite things. It could be anything, food, books, TV, shoes, colors…

Colors, I like all of the banal default colors—

Which colors?

Beiges and browns, earthy tones. You walk into a government building; I’m really curious about the decisions that go into that color palette. It’s easy to think there wasn’t much thought behind it, but in reality, it was a choice. To be, quote/unquote, neutral.

Neutral. There’s a rabbit hole. I’m just throwing things at you now; favorite hierarchies?

Favorite hierarchies. Can you elaborate?

We talked about how people naturally put objects into a hierarchy, living things at the top, but also we put people into hierarchies. I asked you favorite foods, that’s also a hierarchy.

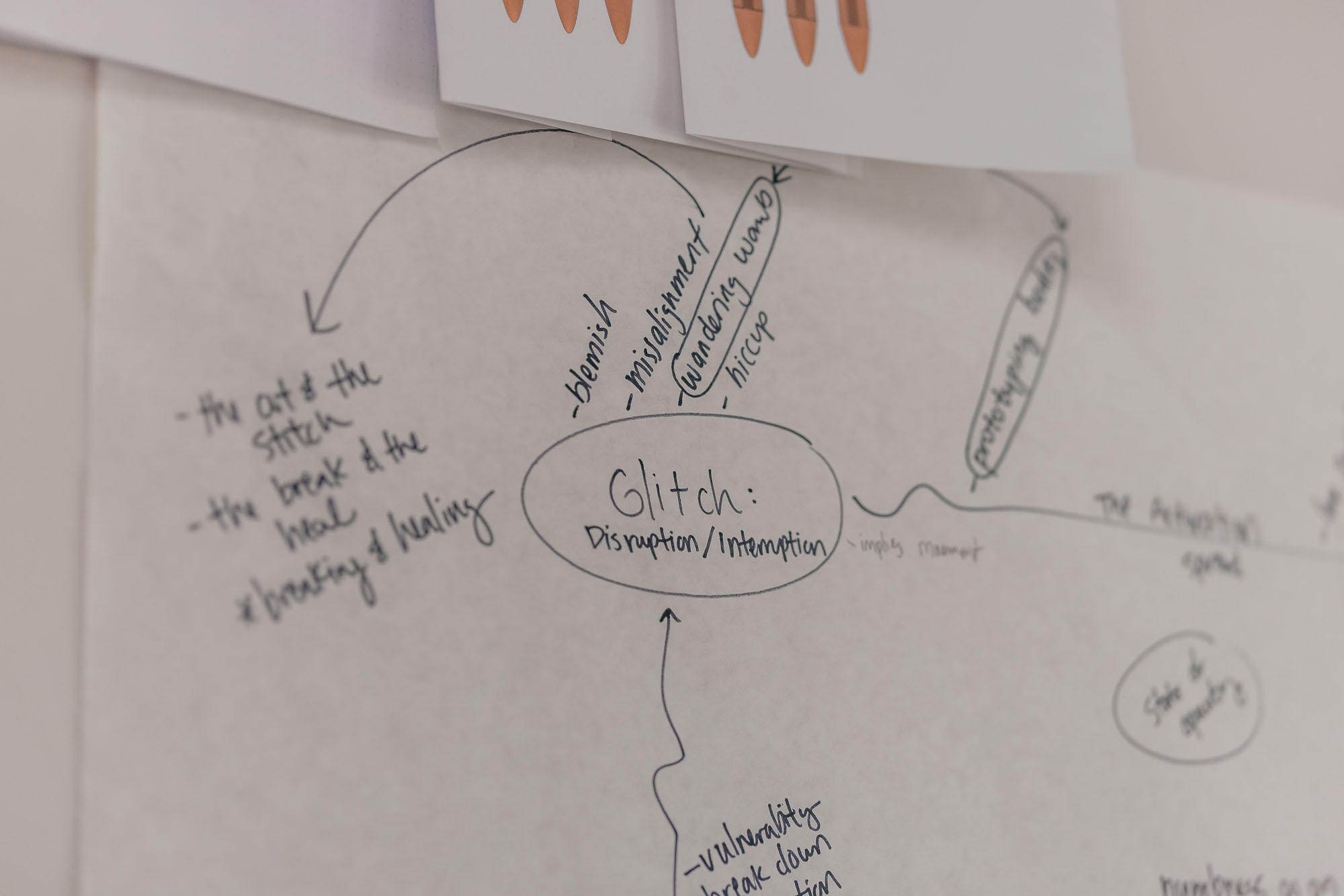

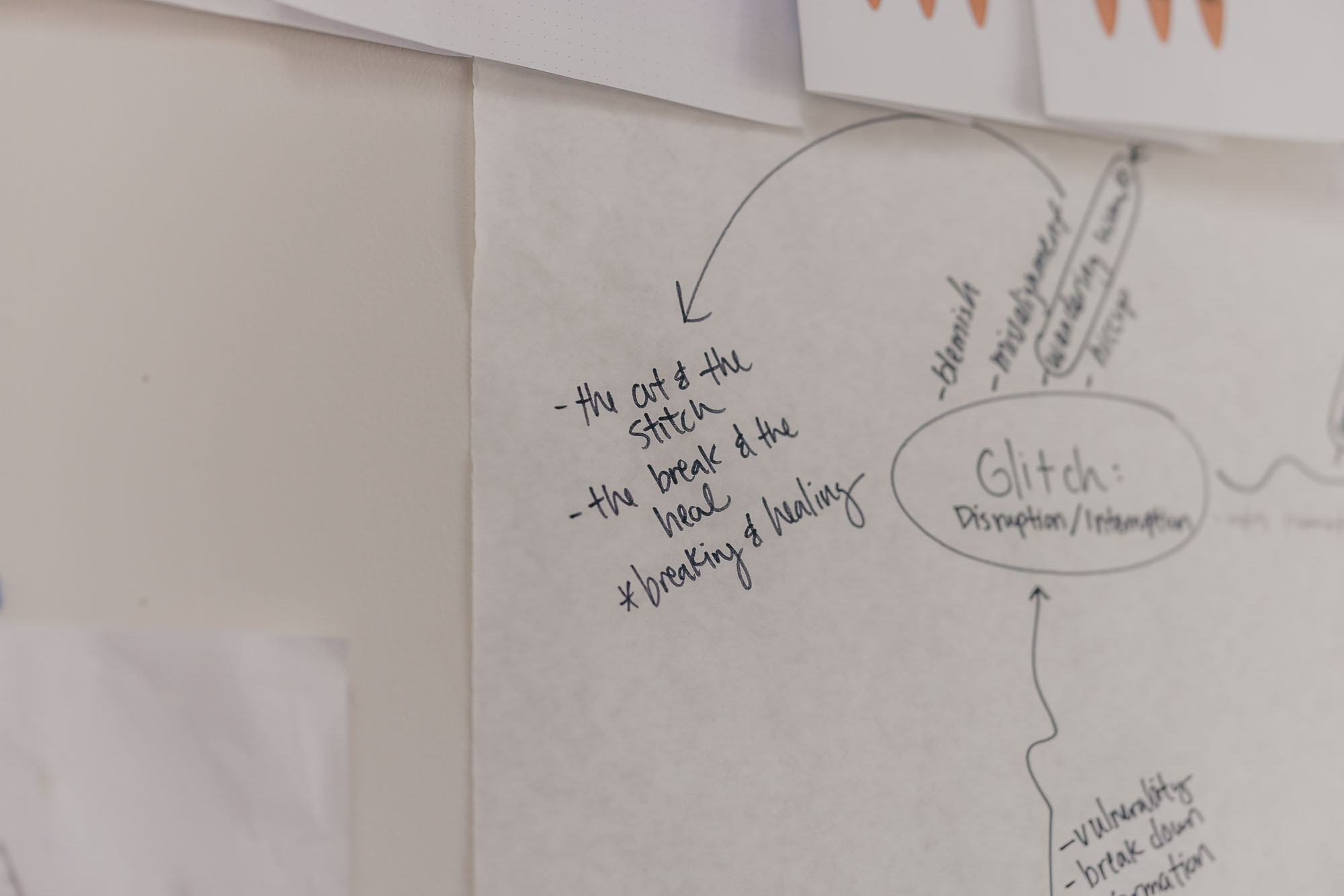

I mostly like disrupting every single hierarchy I can find.

Such as?

Whether it’s, like, the most important thing—either for its value, or its significance, I like putting it in the corner. I made a broach replicating the gridded pattern of tilework, drawing attention to the grout, the in‑between space. At the intersection of those colliding lines, I have set stones.

In art history, tilework makes me think of the byzantine mosaics, church interiors, sanctuaries, and sacred places.

I was about to meticulously set stones, but looking at all these glistening stones, moving them around my hand, the light bouncing off all of the facets; I wondered, “Am I too hypnotized by this material, is it undermining my concept?”

And?

And so I sandblasted them—

No!

They were no longer sparkly. It was all about the act of catching and holding, how matter gets swept into a corner, the gesture. They became like little pink blisters—

Ick.

I had a box to display it. In an interior corner of the box, away from the viewer, I carved a seat for another stone. A sparkly, shiny thing, not sandblasted, and did the act of catching the stone in a corner, in a hard‑to‑see spot.

Aha. I see.

You have to work for it, you have to take the time.

Well, and that’s hard—

I know.

If you like disrupting hierarchies, does that mean you gave your parents a hard time as a teen?

I don’t know. I still struggle a lot with the conservative, patriarchal, traditional upbringing I had. I was a pretty good child, I think, and teenager.

Pretty good or pretty compliant?

Compliant, yeah. But even to this day, I really struggle with being shaped and molded how I once was, to how I actually think and feel.

That could be a whole separate interview.

It’s like a shadow you carry around, something residual you can’t shake off, deep in your psyche. I think of it as a long, ongoing process of undoing.

What’s something you’re proud of?

I’m really proud of the general investigative nature I’ve developed as an artist. If you have something to investigate, it gives you food for life when it comes to art‑making.

ONE more question. You talked about bringing up the value of objects. Does that translate to a humanistic point of view, say, raising up the value of people?

I think it’s a very feminist position.

Or raising the perceived value of people whom you were taught to devalue?

You can draw parallels to the things I try to do in my work. For one, I’m not presenting [the viewer] with a clear-cut identity. You have to be okay with the objects’ queerness, that you can’t fully access them.

Why can’t I fully access them?

Because they’re unknowable in their entirety.

Why?

Because you’re always going to approach them with your own self, your own lens, your own prescribed ideas, and because they are a bit slippery. They don’t easily fit into one singular category.

What do you mean by the objects queerness?

Because they are queered.

I think I need to be educated on that.

There’s a relationship between queer theory and feminist theory. For my work, I would also pull in an ontology. I see an overlap. If you think about queer theory in terms of, let’s just say gender, typically in Western schools and cis/heteronormative thought, we’re taught there’s one gender, two genders, as opposed to understanding that gender is a full spectrum of existence, it’s everything all the time. Anything. That’s the reality of existence. It doesn’t fit into a binary.

So to be queered means—what?

Is to have an existence that’s—

Nonbinary?

—that is nonbinary.

So your objects are queered—for instance, I looked at that one and said “That’s vaginal,” but I didn’t say “It looks like a vagina,” because it doesn’t, exactly. But my interpretation of your work as having a gender is relying on my perspective of biology. And your objects are challenging my projection of gender onto them.

We could also get into the idea that biology doesn’t necessarily equal gender.

My daughter is trying to explain that to me right now.

Male and female. Or, man and woman. Gender is an act that we perform.

This is new to me.

Think about a drag queen, it’s a performance, right?

Uh‑huh.

There are things that are born—

Wait, am I performing gender right now?

We all do. Biology doesn’t dictate our gender.

We need another interview.

I think when something becomes queered, it opens up the vastness of possibility, and creates a space.

Flexibility.

Flexibility, freedom.

I like freedom. Ok, I lied, one last question. How do you feel about being in James Castle’s old space?

It’s very surreal. I’ve never been in a position where I’ve really considered a singular individual’s existence, within a site‑specific geographical location.

You’re walking in his footsteps.

Especially the first few weeks it was inescapable, I would constantly be thinking, or gazing out the window and wondering about his lived experience and speculating as to what it was like. I’ve felt as though I’ve been in a conversation, a back and forth.

He’s in your head. Are you drawn to certain works?

I’m intrigued by some of the moments in his cardboard constructions. He used a lot of string to hold things together. But if you think about the most pragmatic, direct way to way I would be putting a hole through it and using it like a stitch. We know he was fascinated with buttons, because it shows up on the codes.

He knew about buttonholes and stitching, but he chose not to do it. He wrapped instead.

It’s almost like—he wrapped it in a way to preserve the cardboard? An acknowledgment that the cardboard is a stand‑in that should not be pierced.

Should not be wounded?

I don’t know. It does something in that it renders it more like a means to an end rather than a representation of the actual thing. It’s like stand‑in. Too much of a stand‑in. But the methodology of how things are put together and how you can bring meaning to technique and process, I mean, that’s why I’m wholly interested in craft.

Is there something that might inform your work going forward?

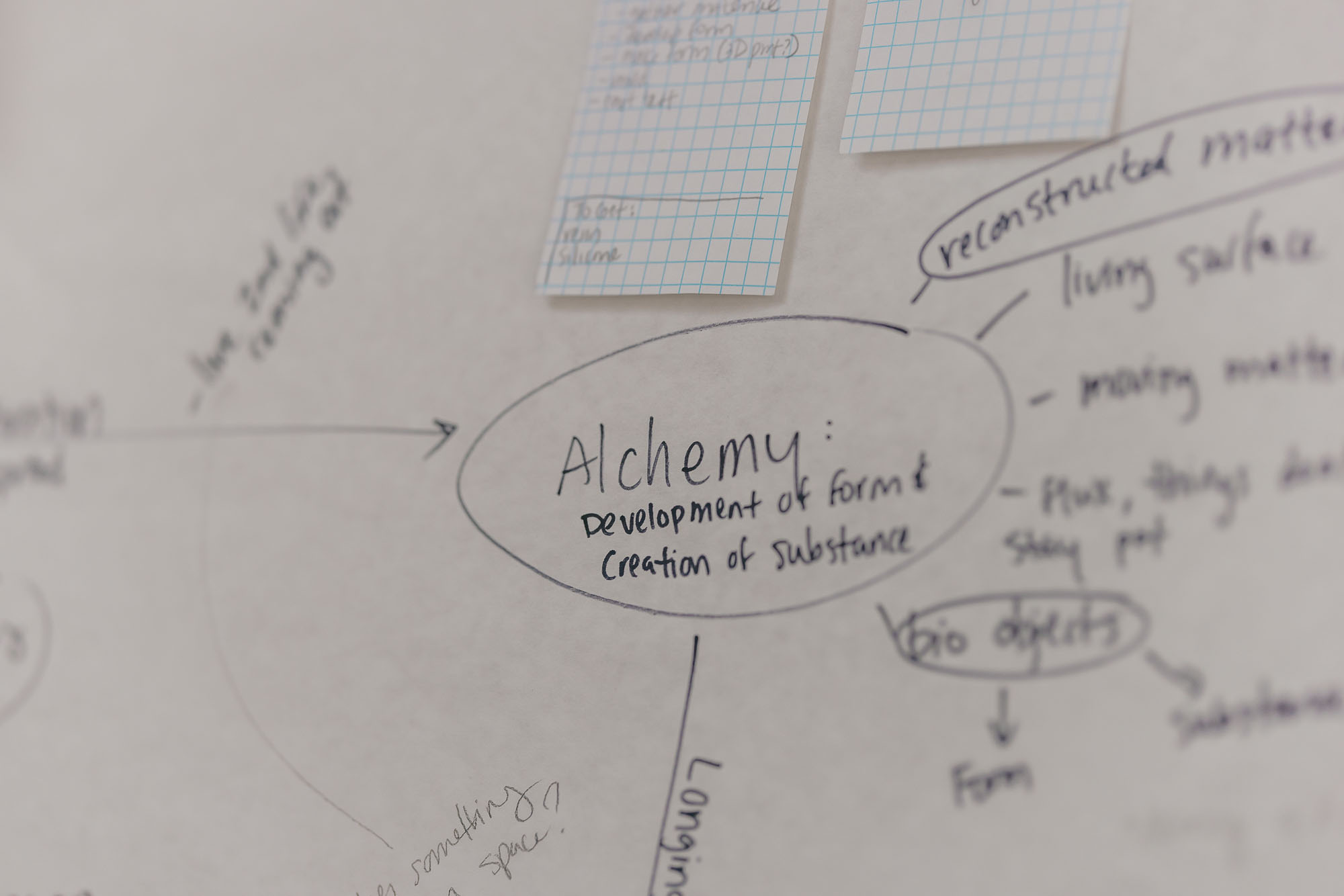

There are things more poignant, perhaps, that I’m curious to see if they find a way into my work. The soot drawings, mostly because they are made with saliva, the alchemy of body and material coming together to make something new. I’m kind of curious how can I use my body as material.

Are you figuring it out?

I’m working on some stuff.

You’re not going to cut your foot off, or something? Are you?

I mean, this is like a really complicated problem to try to solve, so we’ll see.

West End

July 27, 2022

James Castle House Artist-In-Residence

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History. The views expressed in this publication are those of the individuals interviewed.