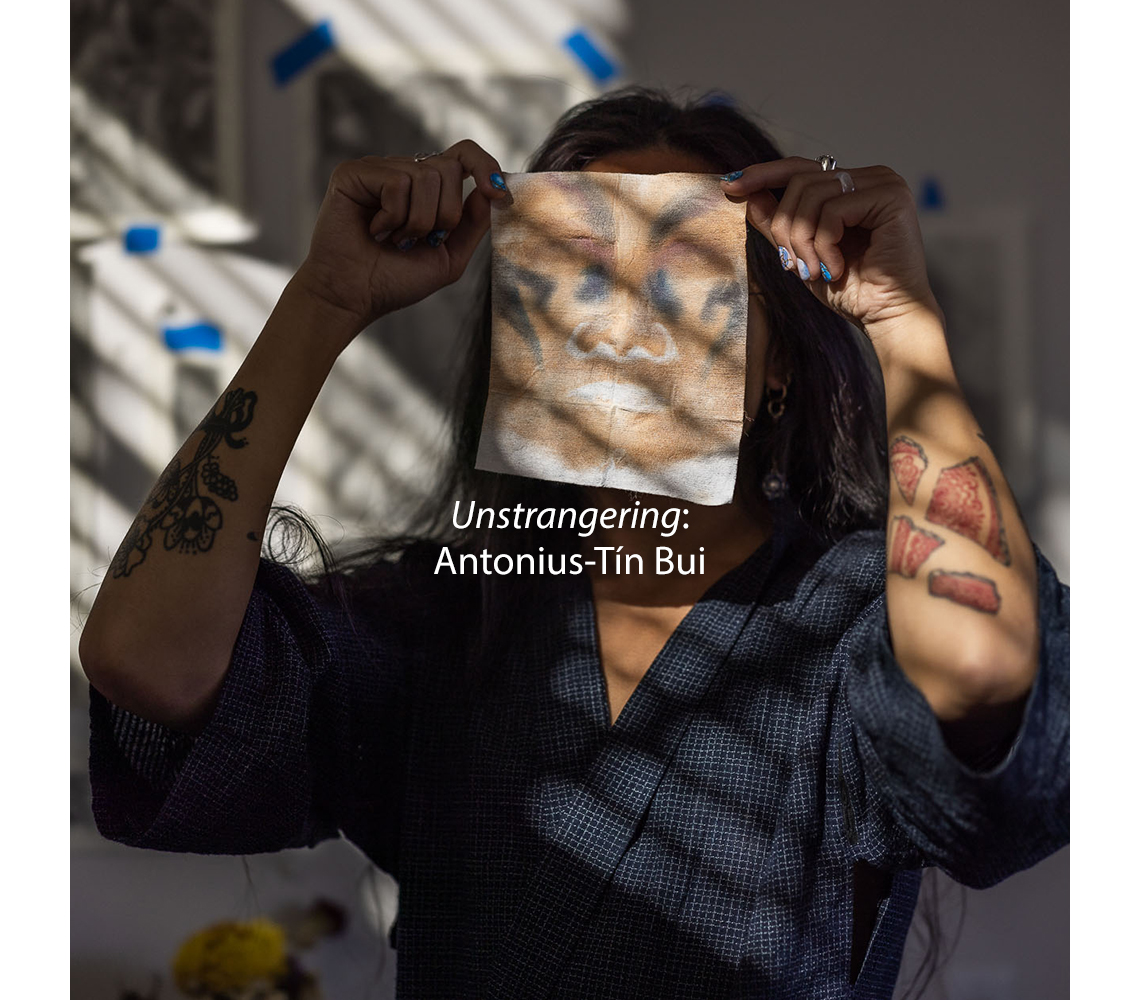

Creators, Makers, & Doers: Antonius-Tín Bui

Posted on 11/3/22 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History

Antonius-Tín Bui is a self described polydisciplinary artist working with cut paper, portraiture, and performance art. We spent a morning in conversation about the unique opportunity to simply play within their creative process, a luxury of a ten week residency at the James Castle House. What does play look like? For them, it’s getting grounded in an unfamiliar space, trying new materials, and discovering what your spirit is really craving, even if it means experimentation: trying, failing, trying again. As a child of Vietnamese refugees who identifies as queer, Antonius describes letting go of the tendency to sacrifice parts of your authentic self for the comfort of others, and the value found in sitting in discomfort as a place of possibility. Most importantly, they shared with us a buoyant, positive energy felt through a purposeful choice to honor each and every person they meet; a simple act of unstrangering.

Are you a morning person or a night person?

Are you a morning person or a night person?

When in residency I am an all‑day person. I treasure that luxury, not having to bend towards anyone else’s schedule. As much as I miss my doggie, Miss Dada, it’s really nice not having to worry about it. [Laughing.]

You talked about allowing yourself freedom to play?

Yes, the spirit of James Castle is very, very present here. Upon arrival I immediately felt him. It’s a very nurturing one. He almost gives you permission, through his gentle touch, and from being in conversation with his work, to play and to really trust your intuition, your impulses. I have ten weeks of freedom to map out my creative practice however I wish.

We talked about the creative cycle as focused on product. When you give yourself permission to play does that change?

It really does. In a capitalistic society, creatives, artists, cultural producers—we are constantly hustling, freelancing. We might be invested and passionate in many of these projects, but when it comes down to what you genuinely want to create, what your spirit is craving, it’s not about the final product.

What’s it about?

It’s in the process of experimentation, of failing, of trying new materials. For instance, I am not a trained dancer, whatsoever, but I love to move. Walking around Boise, I noticed a way that people carry themselves, walking downtown or on the bus. I like to carry these observations back into the studio and practice them myself, interpret the way a kid reaches out to their mother. Outside of residencies, I don’t think a lot of artists have the opportunity to spend a day, a week playing in this way.

Observing and reacting in real time?

We’re constantly thinking about the next exhibition, the next sale, the next contract, applying to different opportunities.

How do you describe your work for people who are unfamiliar?

I’m a hot mess. [Laughing.]

Genuinely so. I own that. In artspeak I’ve been using the word polydisciplinarian instead of multi or interdisciplinary which are two common labels artists use. But I use the word poly. Thinking a lot about polyamory and my genuine equal love for all forms of artmaking. I studied general fine arts at the Maryland Institute College of Arts. GFA, which is often an acronym for “generally f—g around” [laughter.]

Because it meant you chose not to focus on one thing?

Yeah. Because I’m poly, I want to play with textile and performance and makeup and ceramics. I’m not good at all of them. But I believe each of us brings our individual touch to every single medium. And you don’t know till you play.

Play, even where you may not be skilled, is still valuable. You smile so much! Your energy is very buoyant and positive. Have people told you that?

Yeah. [Laughing.]

Where does that come from?

Trauma [laughing].

That’s partly true. I try not to take myself too seriously, that’s from a combination of trauma and having mentors like RuPaul. I think my buoyant spirit comes from the knowing that life is so temporary, that every single person you engage with on a daily basis is going through their own crises, and I aspire to be as present as possible. And to be of service if I can. I don’t consider myself a Catholic anymore, but growing up in a very traditional Vietnamese Catholic household has instilled many life lessons in me.

My parents are both Vietnamese refugees, and seeing how they navigated their lives in a country they never imagined having to call home with such grace and flexibility, and how they built community and organized on behalf of other people taught me a possibility of how to navigate this world.

I say trauma because, visiting Boise, and many other places in this country, is a deep adjustment coming from New York, New Haven. The first week here I remember seeing trucks with Confederate flags, Trump signs, [who would] slow down, or stand down—I talked about observing choreography—when I’d walk downtown, people really craned their necks, eyed me up and down, oftentimes with a look of skepticism and disgust.

That makes me sad.

Going through these experiences, I try to continue to be my most authentic self, to not cave in to fear, to recognize that we all come from different backgrounds and that I might just be quite unfamiliar to them. But by standing in my truth and shining the way I know each and every single person on this earth was born to do, we can unlock more possibilities in people. There have been so many brilliant people I’ve met in Boise who have welcomed me with open arms, invitations to join them at events, parties.

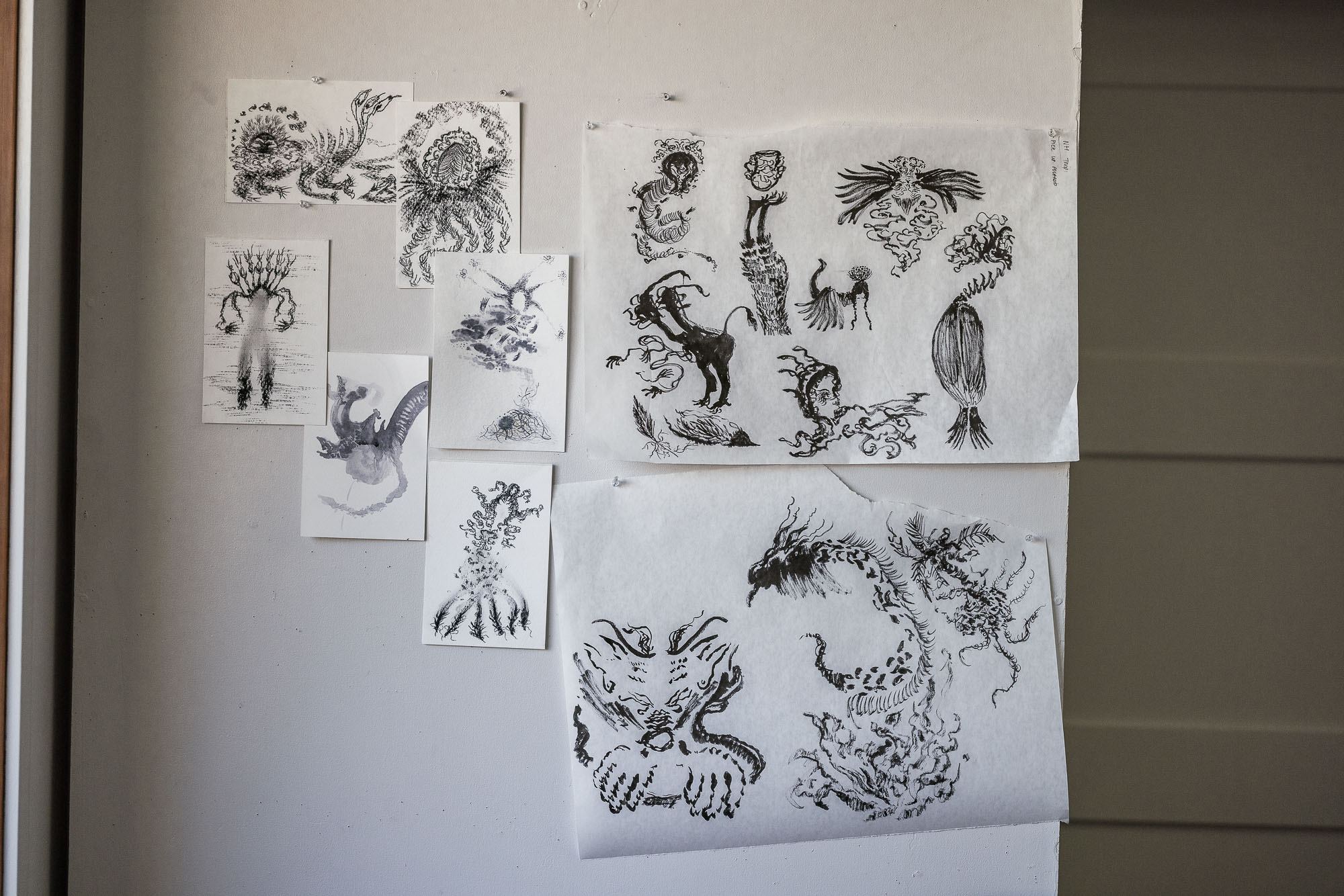

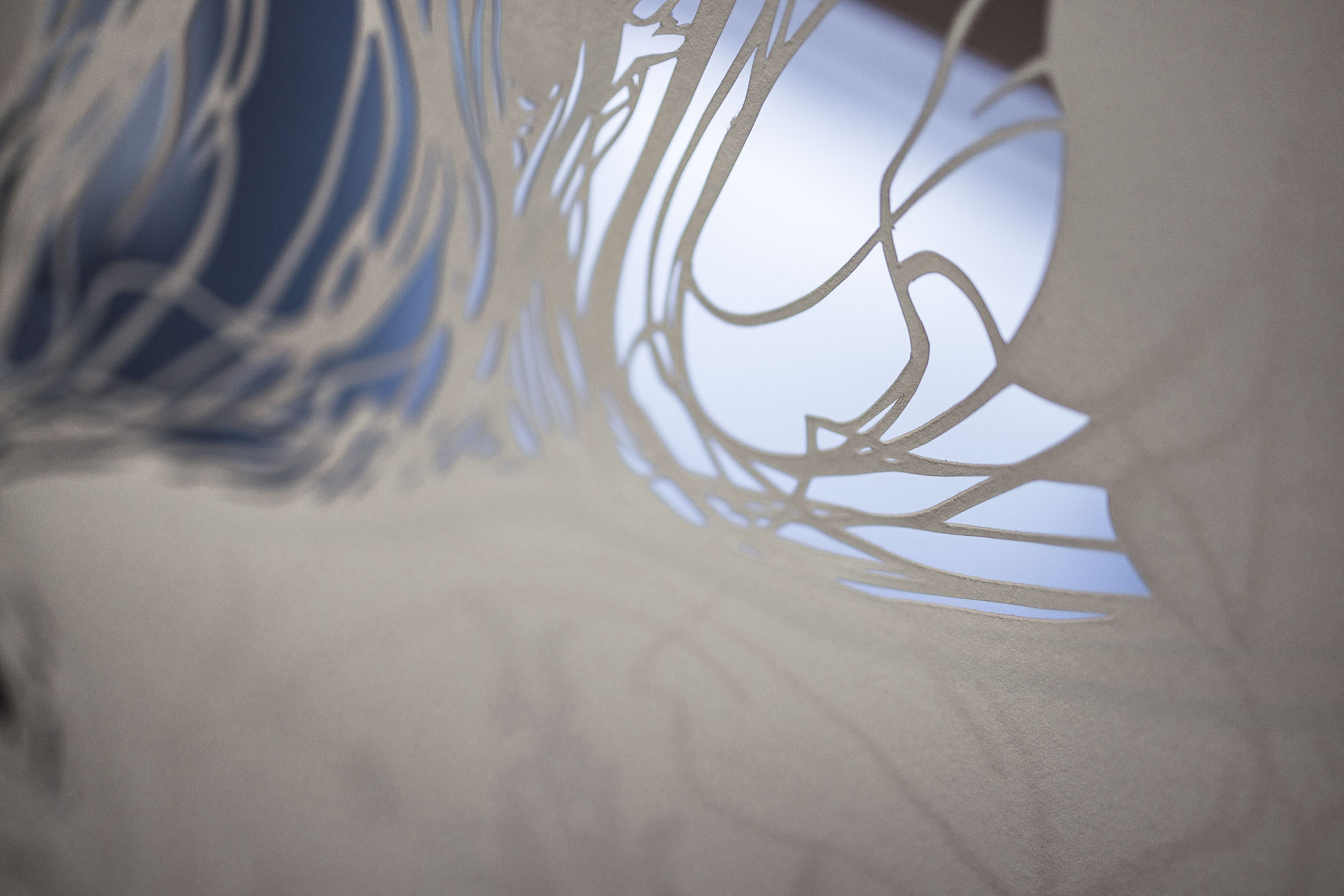

So, polydisciplinary. We’re surrounded by ink drawings and cut paper. And makeup. And I see just a hint of glitter.

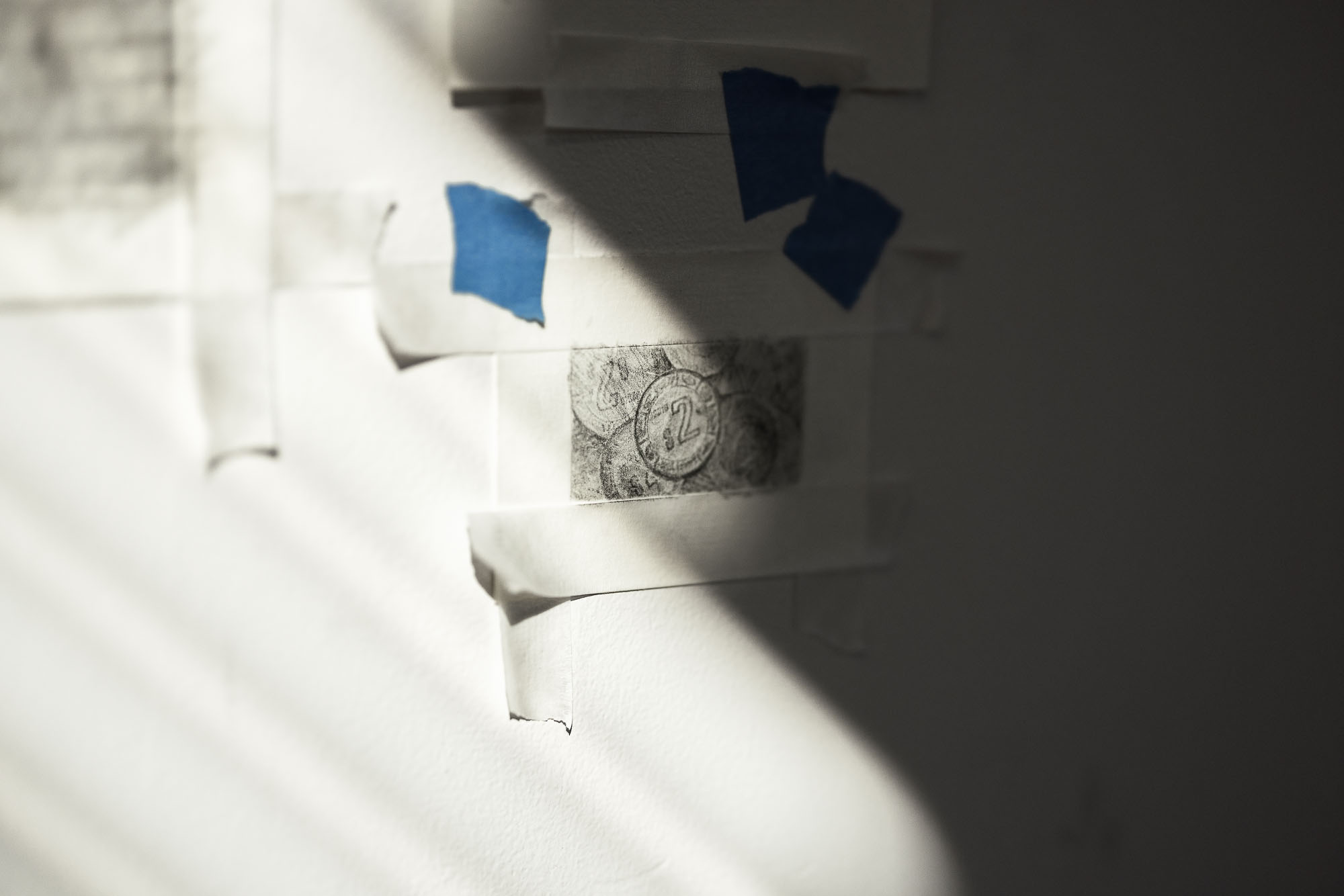

At home, I work in a small third bedroom with slanted ceilings and walls. Here, I feel as though I can spread and be complete in myself. All of the graphite rubbings were made the first week. They are close observations of the studio space, the museum and outside areas. Doing the rubbings got me grounded. The act of getting on my hands and knees and intimately knowing the space.

I see the texture of the bathroom tile. I see the texture of the pressed‑wood floor. I see the fence. I also see figures, words or letters, I see circles and hair and coins.

That coin was found around the house. I’m pretty sure they leave it behind for every resident. And the text Wade, that is a rubbing of the staples inside James Castle’s shed. The more ambiguous one is of the broken window inside his shed.

Oh, it looks like a figure with ears. A rabbit. I like that these are not specific enough to be recognizable as X, Y, or Z, but they’re suggestive.

I feel it speaks to the universal quality of each of us building out on interior spaces. What does home look like for each and every single one of us?

Well, home is made up of a floor, walls, you know, a fence, a boundary. Broken windows, trauma, maybe? What was your experience growing up in two cultures?

I’m very grateful that I grew up with my grandparents, three siblings, both my parents, and my dad’s entire side of the family. When I lived in New York, I was surrounded by aunts, uncles, cousins, family friends. It’s strange because, yes, we are a traditional Vietnamese Catholic household, but I always love to share the fact that whenever we had large gatherings, the aunts and uncles would ask us kids to put on a fashion show.

Pageantry!

Theater, f—g with gender. They would ask us to create personas, put on a runway, a talent portion, give speeches Miss America style. As we got older that became unacceptable. Or condemned. Looked down upon. Creativity was always fused with my upbringing. And when I was 14, we moved to Houston, Texas, and we were surrounded by my mom’s side of the family and my grandma. The dissonance or displacement that I think many immigrant, refugee, POC families can feel—I’m privileged because I was surrounded by Vietnamese culture. But, I still carry some shame around not being completely fluent in Vietnamese.

Do you feel you are lacking?

I have a lot of regret around not getting to know my grandparents better. If I was more fluent in Vietnamese, I would been able to tap into more conversations with my parents. They are very fluent in English, but some things just don’t translate well. Or some things they may be more comfortable expressing in Vietnamese. And so much can get lost in translation.

Speaking about two cultures—let’s talk about gender. What does it mean to you to identify as queer?

I always like to remind people that for me queer is, first and foremost, a verb; it’s the constant queering of our lives. To queer something is to imagine a possibility, alterity; that there is a way outside of these oppressive structures of society.

Limiting structures?

We very much live in a heteronormative, capitalistic society that assigns value and worth according to what we produce. We constantly ask people to prove themselves: to prove their worth, to earn dignity, respect and safety.

Rather than those things being inherently honored.

So for me, queering means allowing yourself to shape‑shift and transform according to your own will. And it’s difficult. As a queer, nonbinary person, who is also an artist, I still find myself stuck at times, or doubting myself. The polydisciplinary‑ness that you see in the studio, that’s an active queering of my own practice.

Allowing transformation. When your childhood pageants became unacceptable, how did that affect you?

Definitely it inhibited me, in terms of viewing what I considered authentic expression of sin.

I grew up in a traditional Baptist family and experienced the rules about what thou shalt not do. It can either make you to stop doing something or cause you to do something in order to fit within this religious structure.

I very much felt like, ooh, I need to conform more if I want to get to heaven [laughing]. Or to be considered worthy of love from this almighty God.

Do you still hold the same beliefs?

I’ve defined prayer and God on my own terms and still very much so respect the religion that my parents follow. I still go to church when I go home. Honestly, I think all of us are searching for purpose and meaning. And if organized religion allows you to tap into that, as long as it’s not at the expense of other people’s lives, then I’m here for it. If anything, I see God in every single person, every single being.

And there’s some of the buoyancy, right there! Honoring that in each person.

Honoring the bees that are pollinating the lavender flowers around the James Castle House, seeing God in you and the light that you shine, your willingness to come meet me, a total stranger, to photograph my space, which is a sharing of your talents and skills.

I’m honored to do it. What are you reading?

My friend Michelle sent me a poem, One Heart, by Li‑Young Lee. Whenever I engage with poetry, I feel recalibrated and reminded of the beauty of this world and how to reclaim the ugly. I’ve also been reading about the work of Takahiro Yamamoto, a performance artist based in Portland. I’m just going to read you some of the notes I’ve taken:

“Opacity as a proactive resistance. There’s so much pressure to articulate all the time. Why can’t we experience without having to define or clarify right away, leave openness to wonder? So often we are utterly visible, to the point of inescapably identifiable.”

I think the thing is—especially around Boise—I’m so utterly identifiable as queer, gender nonconforming, Asian, femme. Yes, we are developing so much language around diversity, inequity, inclusion, and justice, but it’s very easy to feel trapped in the type of work you have to make. And when you are constantly called to do work of reparations, of activism, of rectifying histories—and that work is so necessary, so admirable—it takes such intense focus and concentration and can be so all‑consuming. But what about abstraction? But what about Dada, chaos, and nonsensicalness?

Balance?

Where is the place for rest and play? That’s where opacity comes in. I’m no longer interested in code‑switching, but I am interested in being able to change my level of opacity.

What is code-switching?

Everyone identifies it so differently, but for me code-switching is intentionally changing the way you present yourself in order to comfort those around you. Oftentimes it entails a sacrifice, having to compromise parts of yourself in order to put others at ease. I think a lot about the importance of sitting in discomfort.

It’s okay to sit in discomfort. But we spend so much energy to avoid it.

Opaqueness is having to clearly know what is. When in fact, discomfort, the, quote/unquote, gray areas, are a space of possibility, of queerness. A portal to locales you never thought possible.

People have a tendency to want to know where they stand. But there’s more possibility in the gray. You said you want to allow yourself to adjust your visibility as you see fit?

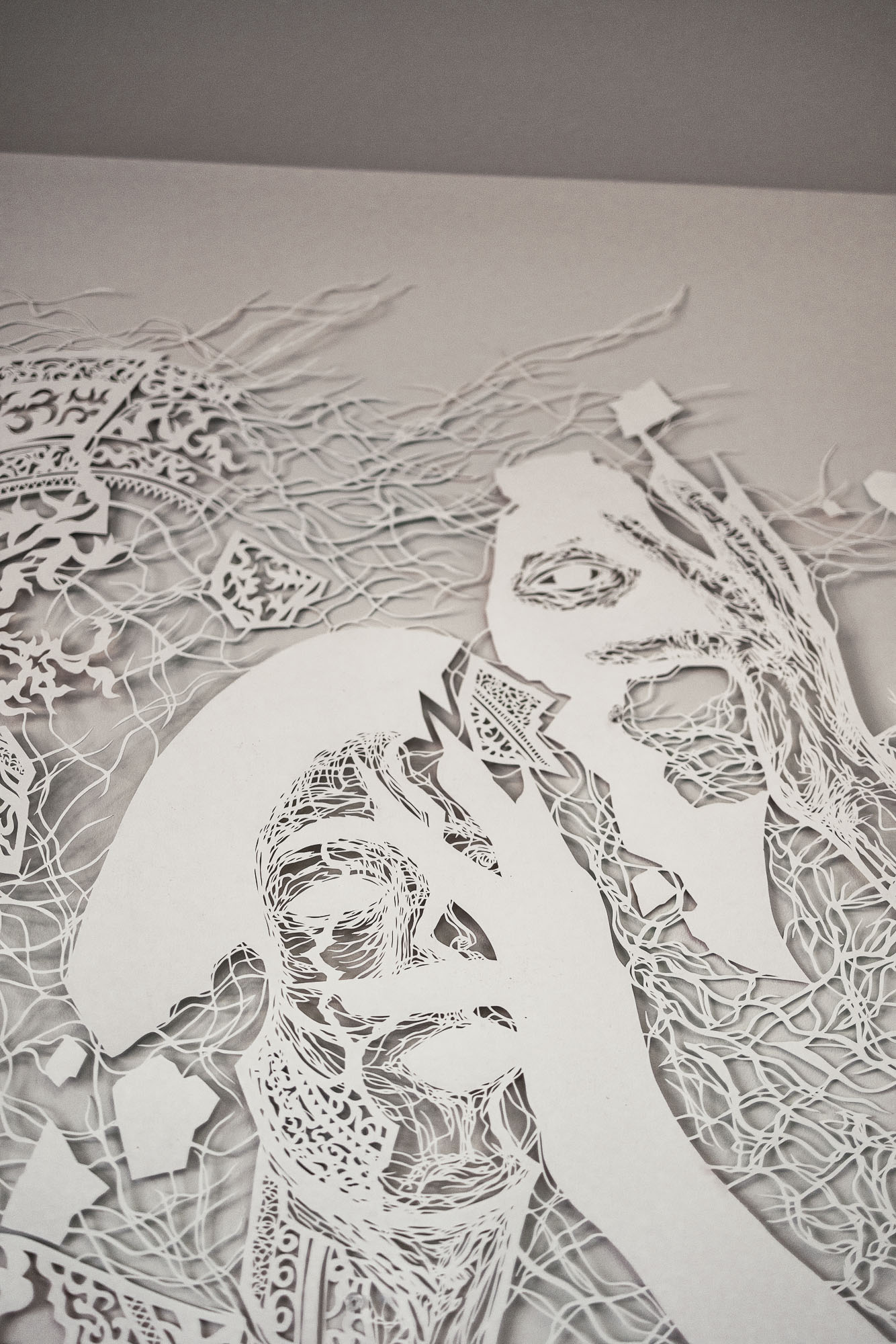

This ties to a new direction in portraiture I’m doing where the bodies are fragmented and glitching. With this new work, I’m combining my body with Vietnamese vessels found in permanent collections. I’m shattering myself, reconfiguring my body into a form that is in flux.

I see doubling. You mentioned that you are entering a phase where something is being born?

I see doubling. You mentioned that you are entering a phase where something is being born?

Ooh, I am beginning to birth my drag persona. I’m finally birthing that creature. Drag has been such an important part of my own formulation and growth. I’ve always seen that creature inside of me, so I’m preparing to birth this drag monster.

I’m excited for you. What’s something you’re excited about?

For drag, music continues to be one of the greatest markers of my life, I can recount eras of my life through albums. One of the many albums that has shaped my studio practice is Rina Sawayama’s latest album, Hold that Girl, it feels like everything she has been thinking about conceptually has manifested itself into the perfect summary of this experience. As I’m listening, I’m imagining all of these drag numbers and how I want to interpret these lines, how I want to lipsync and articulate certain words. But the album, very much so, for me, touches upon healing as an Asian body in this world, reconciling with the traumas of childhood and filling in voids between yourself and your parents. But in terms of what I’m generally excited about—I use the word unstrangering people.

Unstrangering.

Yeah, unstrangering folks around here. That’s what I’m excited about immediately, being as present as possible throughout the remainder of this residency.

That’s a gift. What is something you would like to tell your younger self?

[Laughing.] My first immediate thought was, moisturize, girl [laughing]. In all seriousness, there are just so many cliches of this world that hold true.

I would say treasure every single moment with those who really see and love you. I think we both talked that life can be so long, but it can also be so short. You never know when someone will end up in the hospital or injured or in the grave.

I was thinking about my grandparents. I lost my last grandparent in the time of COVID. I wish I could just sit at a table with them again. I just want to be lectured once more [laughing]. You know, the really simple mundane things. I wish I could hold your hand again to cross the street to church or like help you put on your pearl necklace or compliment your hair after you’ve had it done.

Those little moments.

You lose an entire library of histories, stories, experiences. You really can’t take any moment for granted.

West End

Novemeber 3, 2022

James Castle House Artist-In-Residence

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History. The views expressed in this publication are those of the individuals interviewed.