Creators, Makers, & Doers: Jean Shon

Posted on 7/20/23 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History

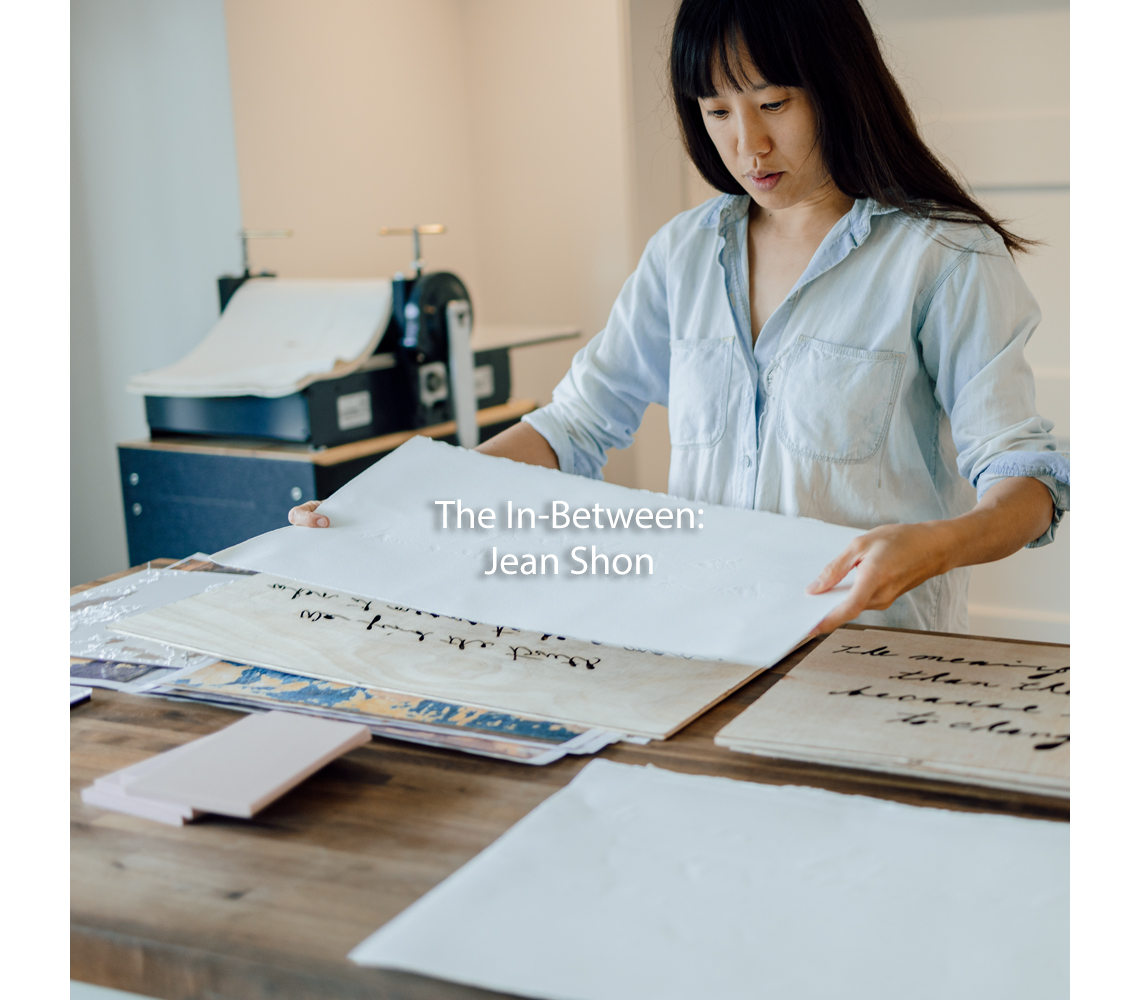

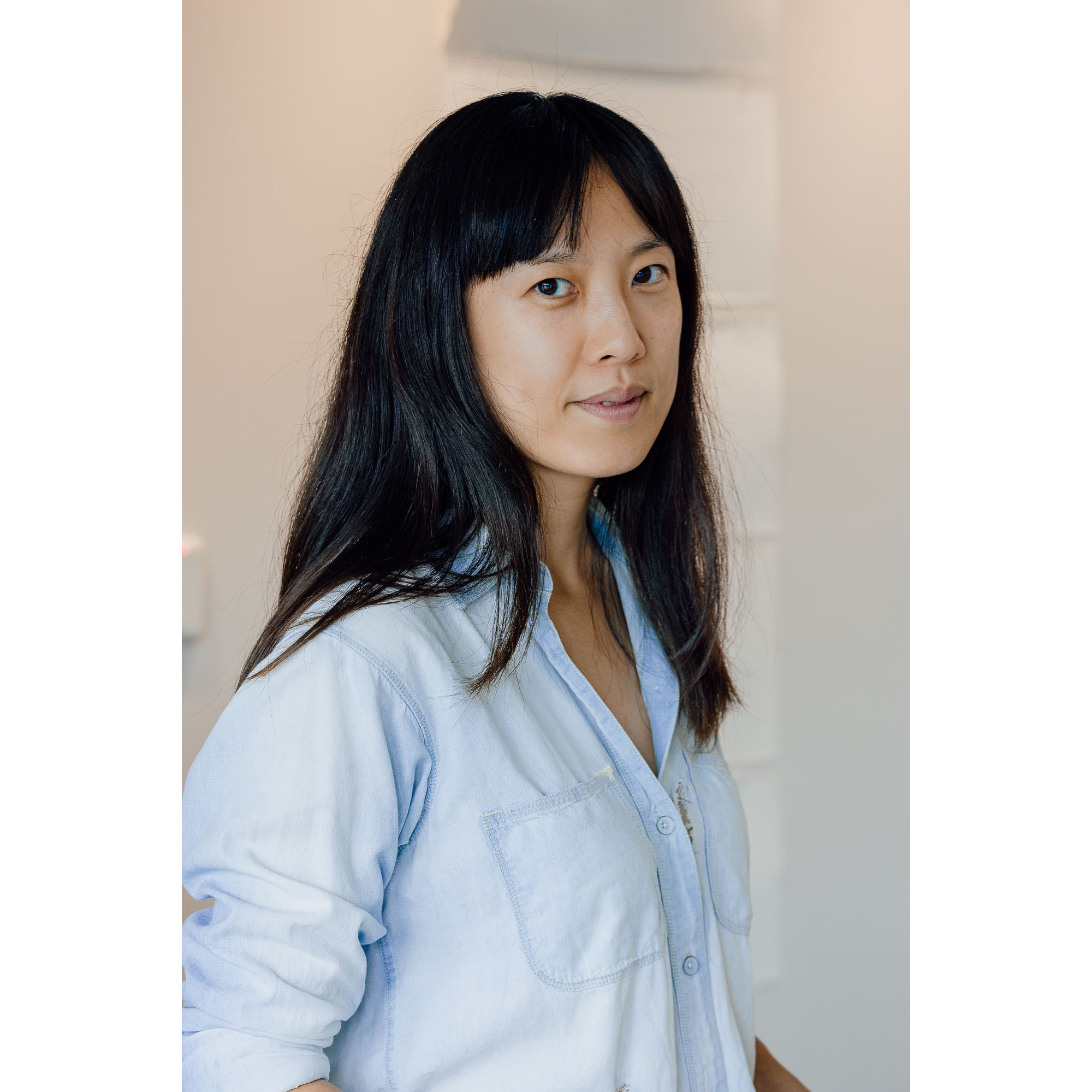

Jean Shon, Artist-in-Residence at the James Castle House, is a visual artist making image based work to create a space for sitting with melancholy and loss. She draws inspiration from memory and from items gathered from her family’s archives: journals, documents, letters. She shares with us about a search for closure; on her father’s death, and the mystery surrounding her grandfather’s death in the Korean War. But what she finds is far more valuable: meaning is found in the in-between, and that honoring your grief, not getting over it, is how you keep your loved ones close. Jean describes her creative process as one of hidden labor and discovery: of herself, her family, and her community. And, we both agree that art can heal, if you put in the work.

How do you describe your work?

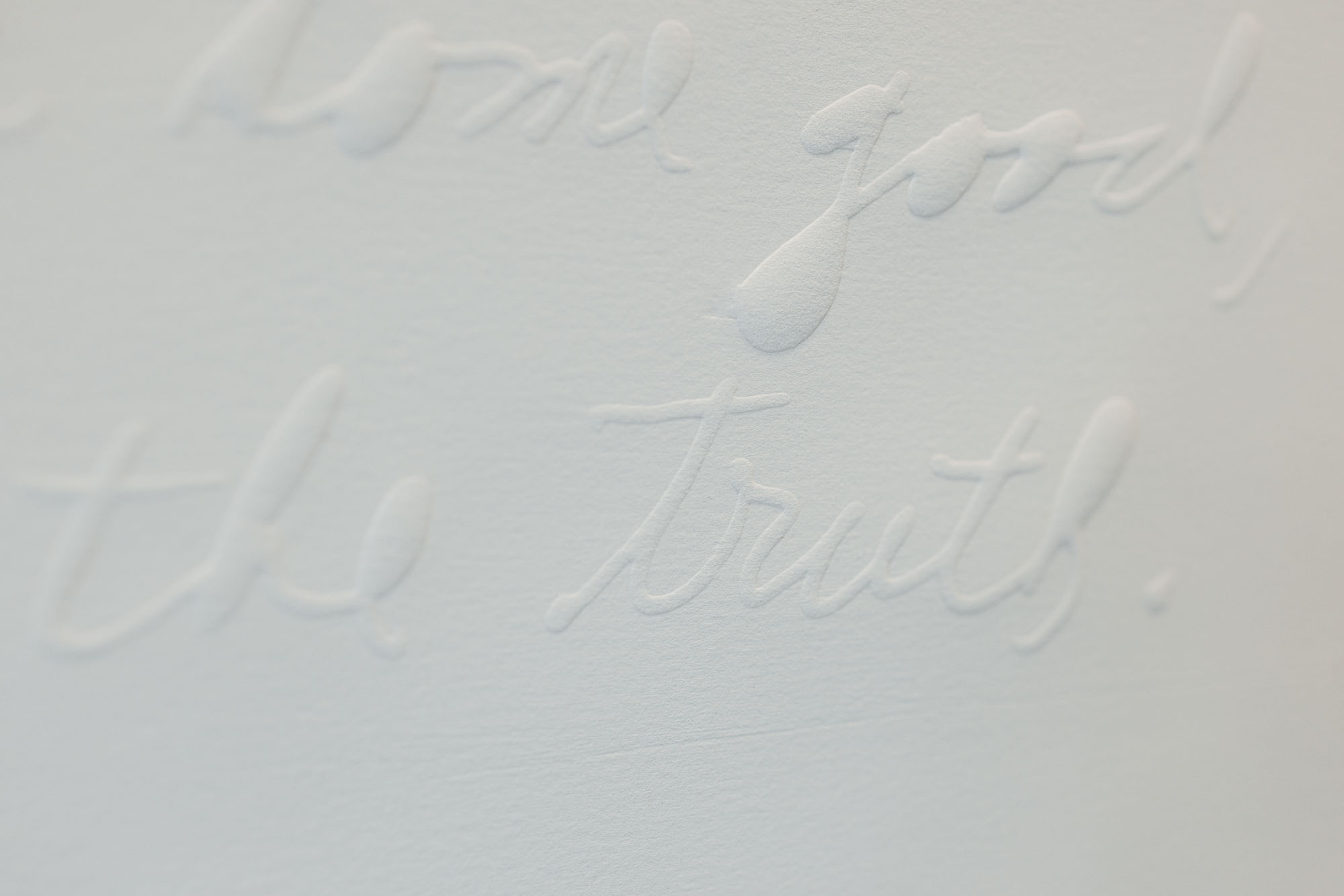

I started with more straight photography, kind of a documentary style, then I started moving towards image‑based work. Still photo‑based, but using family archival things like letters and envelopes, photographs, notebooks, journals.

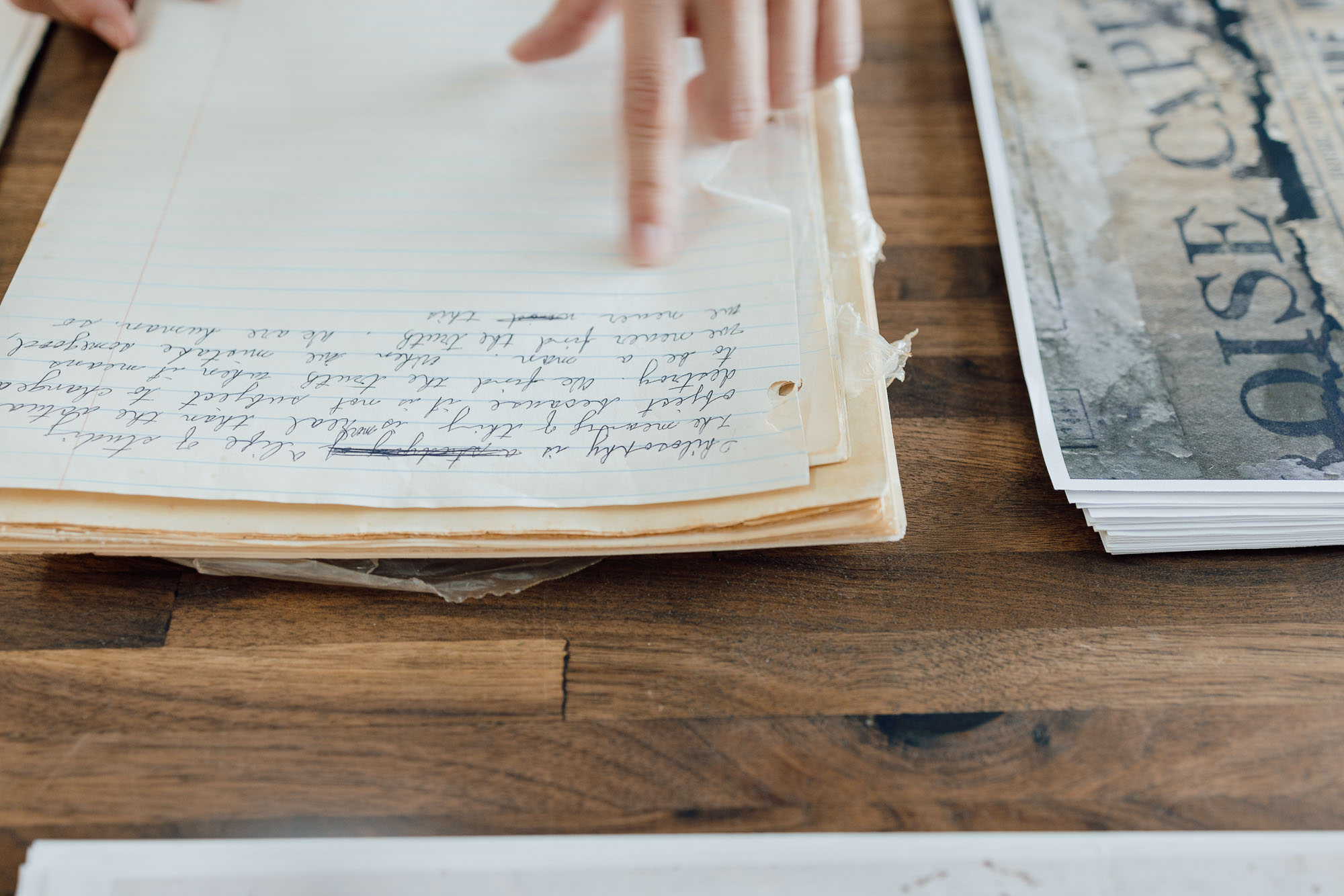

We looked at these pages, things your dad had written.

I started using that as a base. I make manipulations to it. I was making these really large‑scale installations using tracing paper, laser‑cutting text or hand‑cutting designs onto the paper. Manipulating light and shadow.

You’re doing some printmaking? Tell us about these prints on the wall. They’re so colorful.

These are patterns found from the James Castle shed and the trailer. Patterns from the cabinets and the paint peeling, the ground, the window or the walls; stuff I found interesting. I’m interested in things that are left behind, traces of materials you wouldn’t notice until you spent some time with it. The colors kind of represent what was underneath that material, underneath the paint cracking.

What kinds of stories are you drawn to?

I think it’s just the act of learning and finding something new. There’s a lot of surprise in my work, getting to know someone from a different side or a different angle that you normally wouldn’t have, and not just a person but community or whatever it might be.

For example, with my dad, he passed away a couple years ago, I mainly see him as a father, but looking at some of his work before he had kids brings a different side, something new.

A side you’d hadn’t seen?

I knew some of the things, like he’s very meticulous. He’s a good writer, but I didn’t really care when I was a kid. Now, grown up, I can see the kind of things he was interested in; poems he had written down, probably for an assignment, but, I didn’t know he read poetry.

Are you more like your mom or more like your dad?

Oh, probably more like my dad. We’re both very, really organized, you know, particular about specific things. We did find some pages of a journal. I did a previous project on that, a big installation. I wrote some poetry and text based on his journals, using some of his language. My mom translated it for me.

What language is that?

Korean. There was definitely a side to him I didn’t really know, his longing to be back home. When he joined the American military, I think in ’76, he was stationed in Korea for a little bit, so he was able to go back and forth. But once he got settled in the US, he never went back to Korea. That was over 30 years. He never got a chance to go back before he passed away. He wrote letters back and forth to his mother who was still in Korea. There was a strong relationship with his family.

But he never got to go back?

No. His family ended up coming to the US. But there’s a lot of sentimentality. He cared very deeply for his family and his place of home. His father died when he was a couple of months old, in the Korean War; I created a piece talking about how he wished he could take care of his [father’s] grave. There’s a lot of love and longing.

That’s the melancholy you talk about in your artist statement.

I think it’s this idea of like staying—I don’t know, staying within something—

Sitting with it?

Sitting with it?

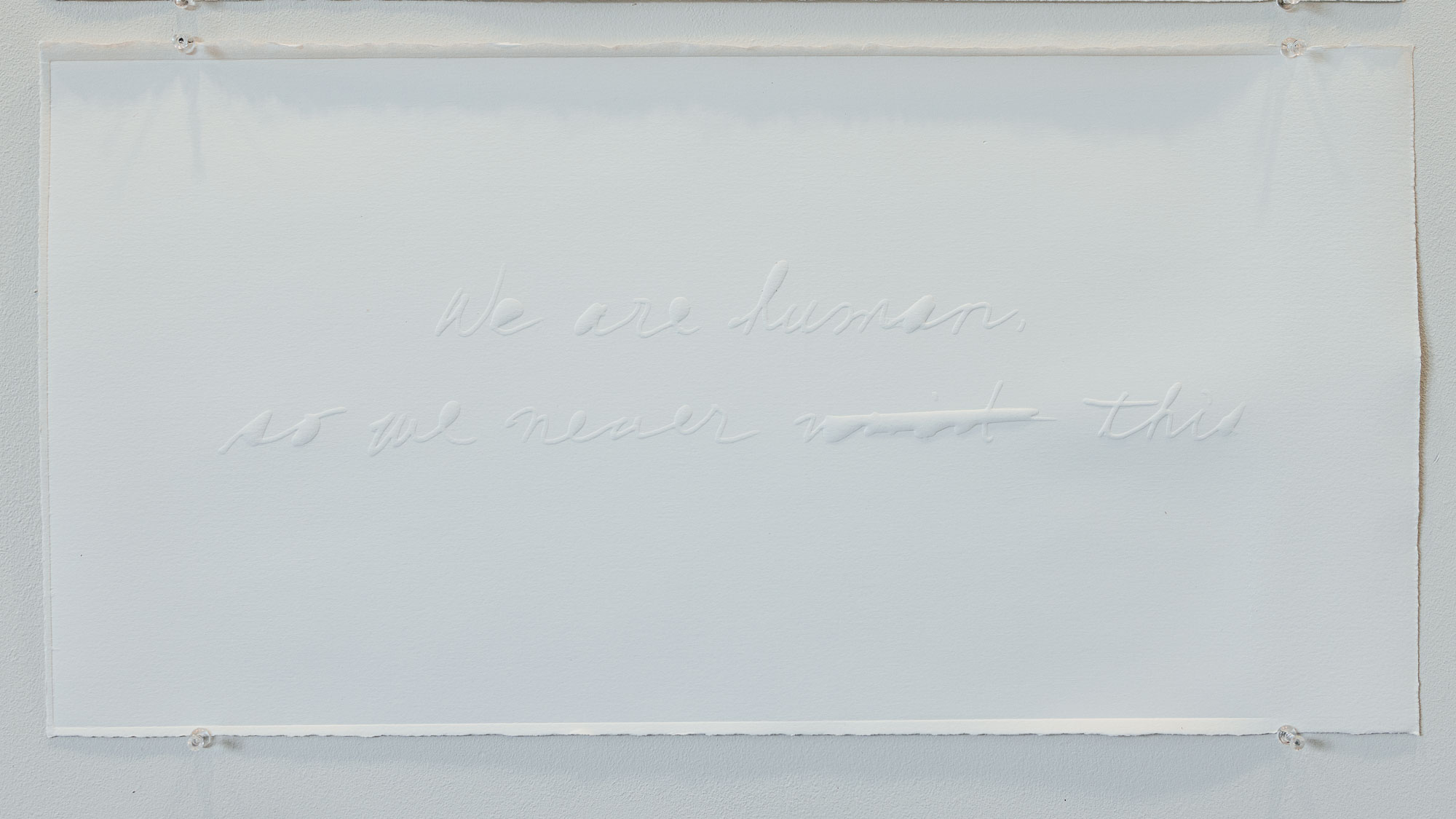

Yeah, sitting with it, versus having to get over it, something like grief. Melancholy is something that stays with you. I’m trying to think of it more as, I don’t want to say positive, but think of it in a way that is sustainable. It’s not being dour or sad, or constantly thinking about the past; but, it’s a way to keep someone close. A desire to keep that loss with you versus getting rid of it or getting over it.

To honor the loss maybe?

I think a lot of my work is to honor, or, a memorial; a way to keep things remembered. On my dad’s gravestone—he’s buried in a National Cemetery—my mom chose “Always remember.” It’s kind of a trite saying, but that’s the reason I started creating this work, if I don’t do it, then nobody else will.

It’s a very human thing, the fear of being forgotten, right?

Yes. So, keeping that memory always, always there.

How did you go from an undergraduate degree in architecture to pursuing an MFA?

I did architecture because I didn’t know what else to do. It felt like a good mix of science, math, and art, so I figured I could be okay at it. [laughter]

Do you regret getting that architecture degree?

Do you regret getting that architecture degree?

No, not at all, now that I’m thinking back, there’s nothing else I would get a degree in. I took a lot of art classes, I took the required science and math classes, but I knew once it was over, once I graduated, I probably wasn’t going to pursue it. It just didn’t seem like the life that I wanted.

When you were a kid, did you ever think you would grow up to be an artist?

Never. Honestly, I probably thought I was going to be a librarian because I loved the library. It was like my second home. But, no, I don’t generally plan for more than like a couple of months ahead, I’ve always just taken things as they go. Between architecture and the MFA, I’ve done a ton of different jobs. I had a pretty big gap between my degrees.

What made you decide to go back?

I tried a lot of different things, worked in a lot of different industries, and I couldn’t really find anything that I would have enjoyed. I’d started working for an art school and took some classes—you know, why not take advantage of the opportunity? After that I started taking art more seriously. And that’s how I applied to grad school.

Was graduate school what you expected?

Yes and no. I guess I didn’t know what to expect in a lot of ways. There’s a lot of freedom, and I think I’m used to a lot of structure.

Like having specific assignments?

Like having specific assignments?

Yes. In some ways I’m super organized and you think of as an artist like, oh, it’s people who have paint splattered everywhere. [laughter] I could never be that, that’s not the way I work. So, when you have, basically, limitless things to do—

Limitless options?

—limitless options, it’s actually harder for me. When I first started, I kept myself in a little bit of a box. I realized, like, okay, I need to go outside of that. At school, it’s pretty low stakes, but because I had never been in that situation before, I was really nervous. I was always nervous during critiques and showing my work.

What advice would you give a student going through the same thing?

The first thing I would say is you should take a lot of time before you go to grad school. I think making art comes from your experiences, I’m just thinking of myself, about how in my early 20s, I don’t think I would made anything of substance back then. I didn’t know anything. I was just in a totally different headspace.

Well, talking about pulling from your life and from your experience, what kinds of things do you look back on, to pull meaning into your work?

An exercise I did was writing down all my memories; the same things kind of reoccur, you get the same memories, mainly childhood memories. When my father passed away there was certainly a lot of reflection, but also researching, finding out more. There were a lot of unanswered questions about my dad and his life.

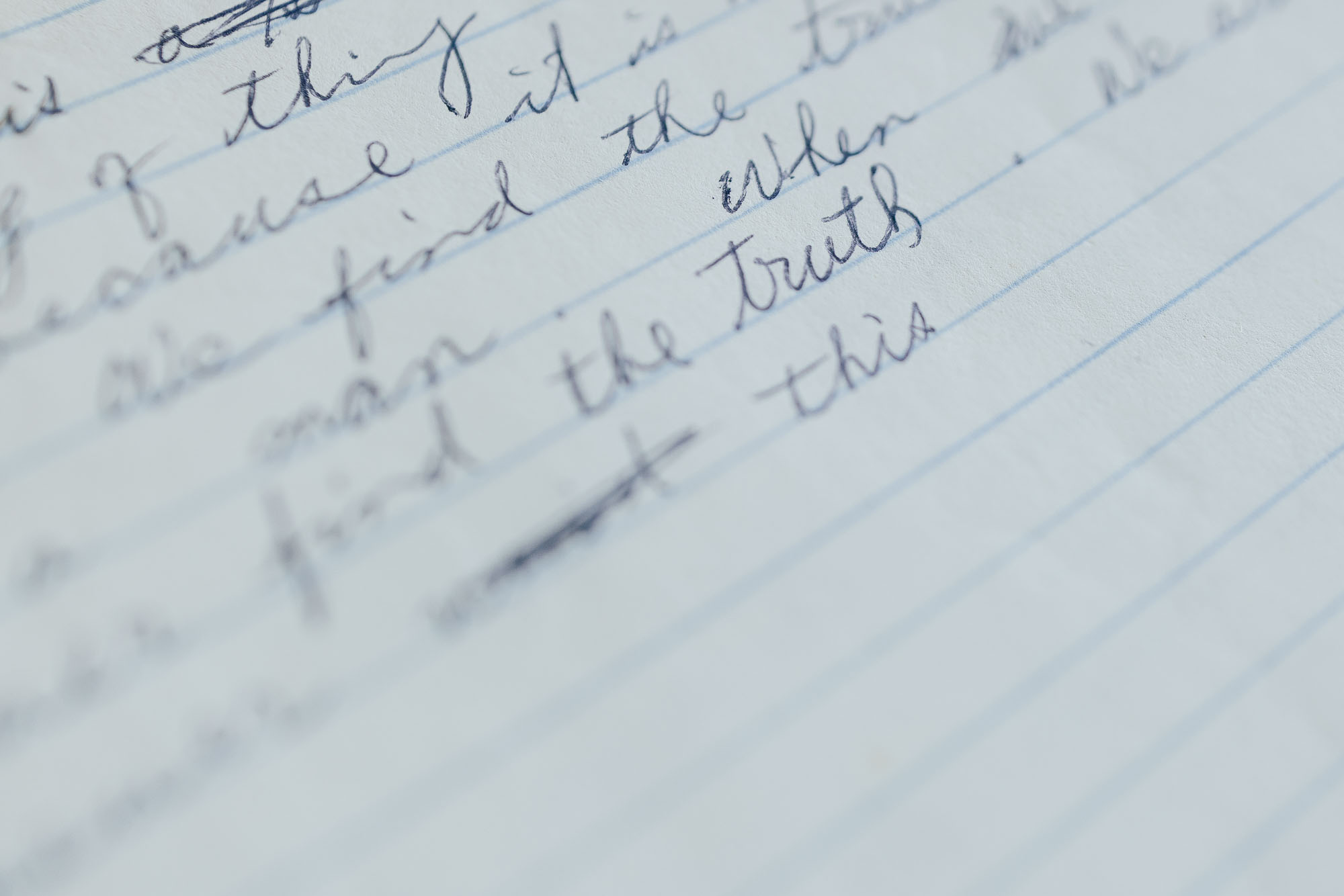

I went to Korea—my mom came with me at one point, and my sister came with me at one point—and we visited his hometown, tried to figure out what happened to his father. We took little clues: we knew [his father] was a police officer, so we went to the police station and found bits of information. I feel like I’m going to get the details wrong, but, we found out that the day he was killed, he was taken away. He said goodbye to his family, and they took him to a jail or a holding cell.

During the war?

The beginning of the Korean War. There were some weird things—his birthday was different from what—

From what you knew?

Yeah. It’s things, like that, weird slippages, where [you question] what is the truth, and what’s not? Maybe it lies in between. With a lot of my work it’s the in‑between.

Is exploring the in‑between a form of healing?

Yes. There’s this book a good friend gave to me, a book of poems edited by Kevin Young. He organizes the book in six stages: reckoning, remembrance, rituals, recovery, and redemption. I was going through a lot of those things, thinking a lot about recovery and healing; it’s a very laborious process.

It’s work.

It’s a lot of work. A lot of the pieces I’m doing require a lot of labor; tedious or repetitive; a lot of it is hidden labor.

Do you feel like art, in itself, is a healing process, or can be?

Art can be very restorative and healing. I think the act of researching or learning or doing it is part of the process for sure—my work isn’t just this final product that you can see. There’s so much that goes into the piece. I think of the research as part of the work.

When you were researching your grandfather in Korea, did learning about how he passed away give you a sense of closure?

I found that the more we learn, the more questions there are. I thought okay, we’re going to find out the answer. There’s not really an answer, it just kind of opens up a portal—

To more questions?

—to more questions. I think that’s with anything. I realized that there’s no real closure. That’s my whole thing about sitting and about melancholy. I want to create a more reflective, meditative space where you are able to sit with it because there is no end or closure.

What do you find difficult about being an artist?

Oh, there’s a lot of things. For me, it’s—it’s like chasing after something and you don’t even know what it is. There’s never an end. That’s one thing. I also always fear, what if I have nothing else to talk about? What if I have nothing else to make work about?

That’s a big one for artists. What is something that comes easily for you as an artist?

I don’t know. I find it really hard. It’s the hardest thing that I’ve done. It’s so mentally exhausting. I have to intentionally carve out time and immerse myself because it’s hard to get into the right headspace.

What’s something you are proud of?

The main thing is that I’m pursuing it. I never thought I’d be making art—actually sticking with it. I’ve done so many different things and I generally quit after a couple of months because I get really bored, or it’s not interesting, or I don’t feel like it’s useful, whatever it might be. It’s not easy to continue.

Is art useful?

It’s useful in that I’m learning about myself, I’m learning about my family, I’m learning about my community, I’m learning about all these things that have meaning and that I care about. And I hope people find value in those things too.

North End

July 20, 2023

James Castle House Artist-In-Residence

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History. The views expressed in this publication are those of the individuals interviewed.