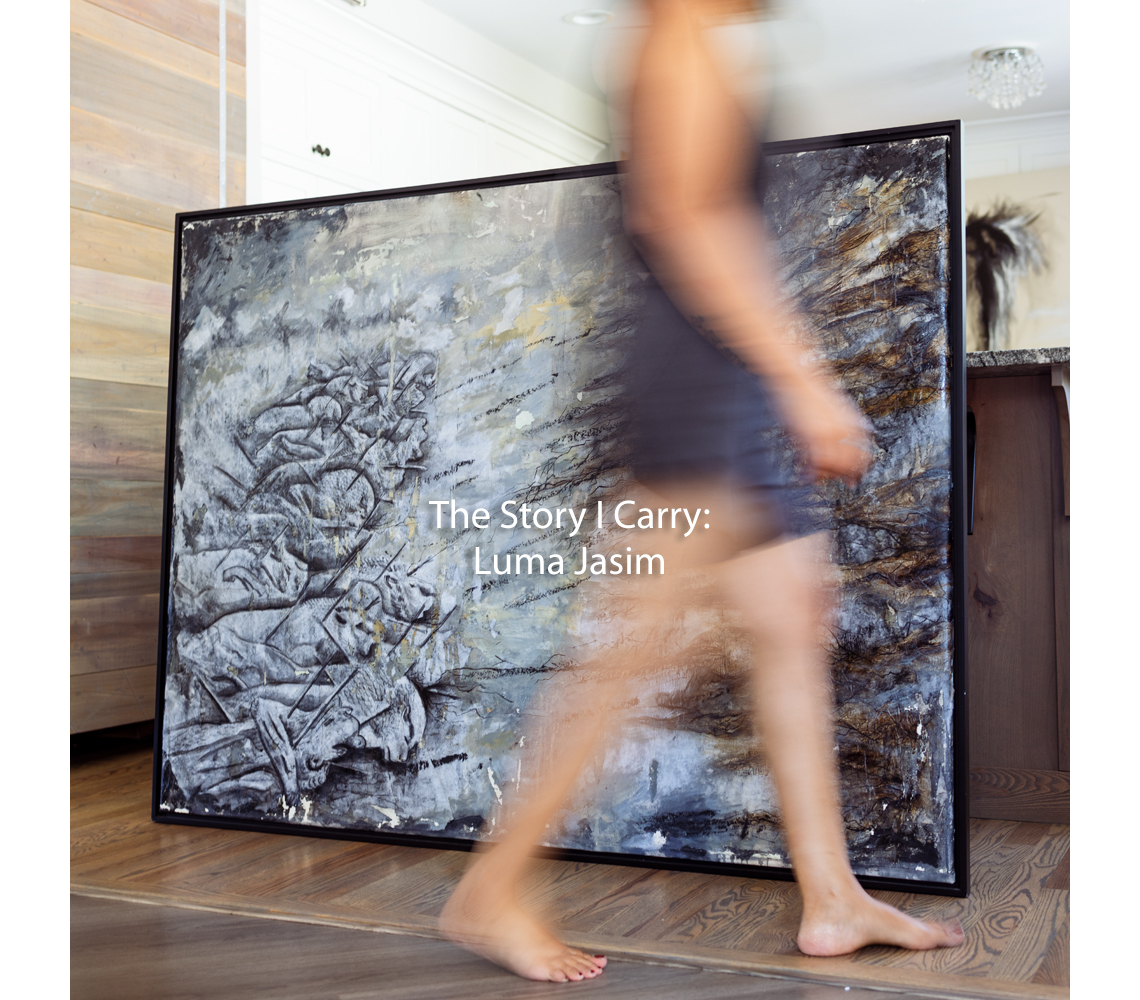

Creators, Makers, & Doers: Luma Jasim

Posted on 9/15/23 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History

Luma Jasim is an Iraqi-American interdisciplinary artist living and working in Boise. She possesses joy, curiosity, and a love for movement and dance; and, as she puts it, a hunger for life and learning. Born in Baghdad, Luma shares with us the heartbreak of one life stolen under the dictatorship of Saddam Hussein, and the beginning of another life after immigrating to the United States. Here, she took the opportunity to find her creative voice, and earn a (second!) bachelor’s and master’s degree, this time in fine arts. During her graduate studies at Parsons School of Design, The New School, in New York, Luma found inspiration in the elevator, just minutes before midterm critiques. It was a way to share the truth of her experience, and it begins with a question, “Would you like to hear a story?” Yes. Always yes.

Do you consider yourself a painter?

Do you consider yourself a painter?

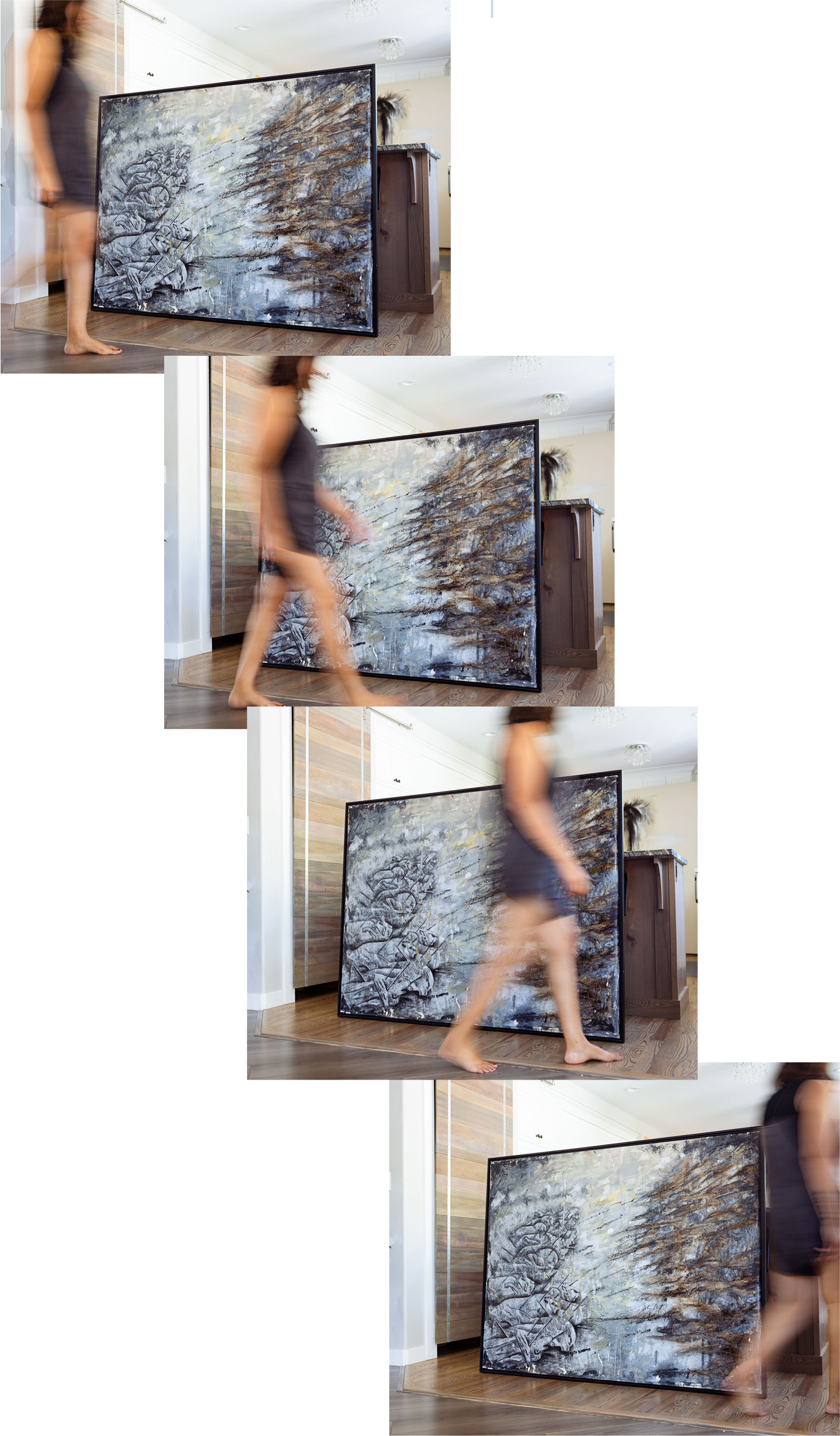

I consider myself an interdisciplinary artist. I work in painting, performance, animation, video, sculpture, and work that involves photography sometimes. I love to try so many things, I get bored working in one medium. I like to surprise myself, it makes me excited and makes me want to know the result of this—it’s almost like chemistry.

You also do performance art? Is that feeling of surprise, that chemistry, like riding a rollercoaster?

Exactly. Especially with performance. With performance, you work hard, try to make a plan, but there’s a lot of improvising on stage. I would get this really bad stomach feeling, before [a performance].

Oh, butterflies in your stomach? [Laughter.]

But then I do it, and I’m good, you know.

You feel comfortable, confident once you get into it?

Confident. Then, you leave it and think, I want to do it again. Like you want to jump, and you are scared, but you jump, and you have this feeling of [inhale breath], but then you do it again. [Laughter.]

You want more! How did you get into the arts?

I started back home in Iraq with graphic design; I worked in animation with a group of artists. I was mostly working digital with graphic design and animation, not because I didn’t want to work on art, but to survive living in Iraq at the time.

I read that you earned an MFA in graphic design in Iraq, then another MFA in fine arts from Parsons School of Design, at the New School in New York?

I was happy and lucky to work in fields that I love. But when I moved here, I started working as a medical interpreter for the hospital.

You’re bilingual?

My native language is Arabic. That gave me space away from working full‐time in the creative process. I wanted to put this energy somewhere, and I found the Quality Art store, and I started to paint. I finally found the time to start my own art and find my voice.

I’ve heard people say that when they have a job in the arts, it takes creative momentum away from their personal practice.

I’ve heard people say that when they have a job in the arts, it takes creative momentum away from their personal practice.

Definitely. I sometimes joke about why they picked Boise. At the UN [United Nations] when we did the interviews and all of that, I’m, like, please, send us to a big city, because I can work immediately in graphic design or animation. I will not be a burden.

When we came here, I couldn’t get into those fields. So I was, and still am, doing interpreting, which I feel was the main thing that got me away from the full‐time art job, and [into] just expressing myself. I started to reflect, and started painting. Then—I want to do exhibitions, I want to know people here; I don’t know how to connect. I decided to get my second bachelors. I went to [Boise State University], painting and drawing emphasis. I have two degrees from Iraq, so I didn’t take the core classes; I jumped immediately to studying art.

Was that good for you?

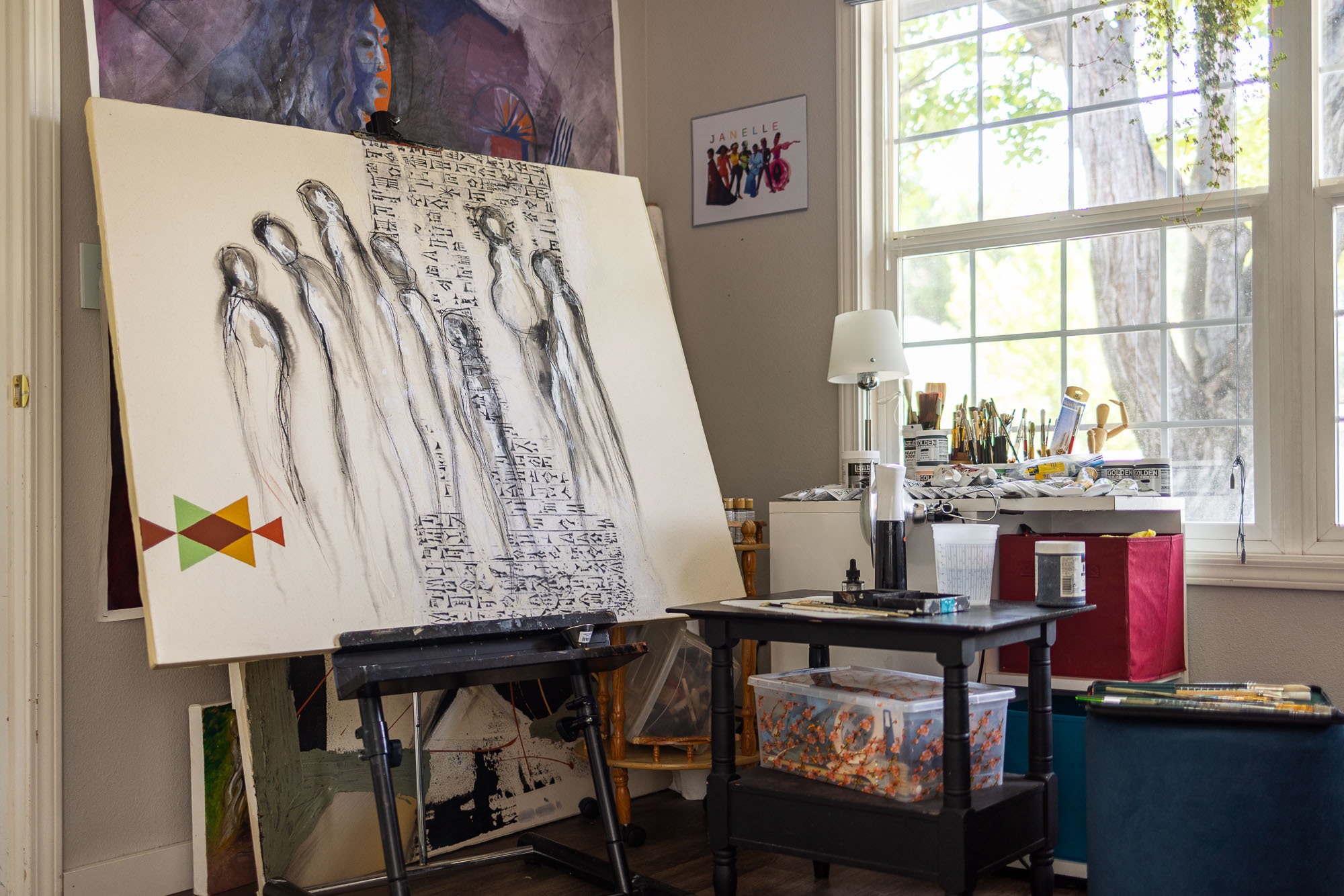

I am someone who’s hungry for life, hungry for learning and making. I took all the classes possible, from cast forming, to sculpture, printmaking, ceramics, photography, painting, drawing—everything. I think the only class I didn’t take was illustration. I loved it. It exposed me to a lot of materials. I started to express myself in different mediums, then started to mix them together, mixed media.

What might I see at one of your performances?

What might I see at one of your performances?

You would see a combination of storytelling, live action painting, projection of animation or video, abstract music, sometimes spoken word or poetry. At the end, it’s a conversation; all the mediums together. I’m affected by the music; I do the painting on the floor, and the musician is affected by what I’m doing. The story and the development, thinking of memories from war…

You allow it to change as you work? Tell me about the storytelling portion.

In New York, in graduate school, the first performance I did was three hours long. It was an open studio, so there were a lot of people coming and going. I covered the space with paper, the walls, the floor, using tar material, symbolizing oil and petroleum because that’s the main reason for the chaos in Iraq. People would be drinking wine and coming to look, while my wine glass was filled with thinned tar, and I’d say, would you like to hear a story? I start, just, remembering stories from the war and what happened. I wasn’t prepared to see people sitting and staying and waiting for more.

People were invested in your story.

I’m telling you, it was three hours; I was telling my story and saying at the end, “But guess what? I survived, so cheers for that.” I’d throw tar on the wall, start painting and scrubbing. By the end, you have the floors and walls [covered] with tar painting. Since then, I’m hooked.

You had been doing sculptural work before?

I did some sculptures in Boise and in New York City, during my MFA studies. I was casting students’ hands, faculty’s hands, and made them look like they are coming out of this oil pool in the shape of Iraq’s map. The day of the critique, or midterm, I was in the elevator talking to my peer, and I’m like, you know what, I’m so tired of people asking me what this work is about. So, I will say, “In 1991, I was in a village two hours away from Bagdad, there was a war, and we needed water and . . .” It was such a spontaneous in‐the‐elevator idea, five minutes before we started, and I just did it.

I told the story of that day—after the Kuwait invasion, how we escaped to the countryside. There was no water, no electricity, nothing. We had to walk to the river to get some water. The siren went off and it went on for 43 days, nonstop. Then you hear the defense, there is an attack, but you are in the middle of nowhere, by the river. It’s open and empty. We started hearing these [hissing sounds] in the water because hot shrapnel was falling in the cold water. We felt that at any minute, something will hit me in the head, right?

I told the story of that day—after the Kuwait invasion, how we escaped to the countryside. There was no water, no electricity, nothing. We had to walk to the river to get some water. The siren went off and it went on for 43 days, nonstop. Then you hear the defense, there is an attack, but you are in the middle of nowhere, by the river. It’s open and empty. We started hearing these [hissing sounds] in the water because hot shrapnel was falling in the cold water. We felt that at any minute, something will hit me in the head, right?

There is something about war and about knowing you are about to be attacked—when the siren goes off, everything will go so silent, you feel like no one is breathing, not even the birds.

That gives me the chills.

It’s so scary. And to hear this shrapnel hitting the water, making circles and making the noise, hot metal hitting the water.

It’s something you will never forget.

It’s like seeing death, but you didn’t die.

Where did you go?

Where did you go?

We drove to our family in the countryside. It was 1991 when Saddam invaded Kuwait. We knew maybe even Saddam would hit us with chemicals. He said, if I leave Iraq, I will leave it just dust or dirt. At 1 a.m., in cold January, the war started. There was bombing everywhere, all the bridges, everywhere. The ground didn’t stop shaking.

Since that critique, where we were sitting on the ground, looking at my sculpture, and I was telling this story, I decided to do performance. I graduated in 2017 from Parsons, and I had so much [to tell]; I just wanted to, like—

Get it out?

—to get it out. I was sick for two weeks after that [performance] because it’s such traumatic information.

Is performance a sort of therapy for you?

I’m not sure about that. Sometimes it’s conflicting; I feel sometimes it’s too much, I feel what I’m doing gets to my body, and I get sick. But I can’t get away from it, whatever I’m saying is not enough. I didn’t tell you ten percent of what I have to share; it’s very important. An entire society has been destroyed completely. The human mind changed from secular to very closed because of these wars and sanctions.

It’s like large-scale abuse?

Abuse. A crime. It is like going in slow motion, you watch, but you have no power to change anything, especially as a woman. Everything I saw when I was little, and hoped for, and that I see as beautiful, was taken away or forbidden.

Do you mean rights?

Do you mean rights?

Yes. The status of women changed dramatically. She was in every field of work, you didn’t see a lot of women with the veil, the religious looks. You see one or two who wear the veil, and you love them, and they chose that. It’s beautiful.

It was a choice?

Yes. But, after the Kuwait invasion, and the sanctions that we were punished with, which lasted fifteen years, everything went backward. You had civilization, then corruption. Education went down, cinemas and theaters closed because the economy went down. Suddenly your salary is not enough for two days and you have a family. What is the point of an education, why do we go to school, if we can’t work? Of course, it’s not everybody, some people, the rich—it depends how much you have at the time.

You said the mind went from secular to closed. What do you mean?

Women, for instance, were working and doing a lot of things in life—they wore beautiful hairstyles, and the fashion, the way they dress, all of that; that’s secular, that’s freedom. It’s a certain amount of respect for the individuality of women and their participation in society. But during the ‘90s, the religion started to grow in a backward way. It wasn’t the religion itself, it wasn’t what we used to know. It’s become corrupted and abused.

It’s almost like a disease that started to grow; people start to switch the way they’re thinking. They start to have their daughters not wear certain things, then “Why you don’t wear a veil?” And then the [United States] invasion happened in 2003, it’s like the feather that broke the back of the camel.

The straw that broke the camel’s back?

Yeah, the feather, we say. It was like we were very exhausted and tired and done with everything.

You were still in the country at the time?

You were still in the country at the time?

Yes, I was in Baghdad. The invasion happened in 2003. I’m one of the people who was like, “Okay, let’s be done. We know the West wants the oil, it’s not about us. It’s not about liberation, it’s not about freedom, it’s not about these big words. We know that.” But at the same time, we were an oil country, and whatever Saddam was doing wasn’t for his people.

When you said, “Let’s be done,” what did that mean to you?

I felt there was no way we could get rid of Saddam. Every time someone tried to rebel, he would bury entire families alive. And if that’s the price, to get rid of him, then: you take the oil, it’s fine. I want to breathe.

How did you feel about how the war ended?

It’s the most disappointing thing that ever happened in my life. You hope for, finally, maybe, a new beginning—and then, it just gets worse.

First of all, we never had terror attacks before 2003. From that day on, it was our everyday reality. A bomb in a market, a bomb in the university. And not one a day, several. There is a picture of Bagdad from [above]—I don’t know, CNN, or who did it—marking a red dot for every explosion from 2003 to 2011, or something like that. It’s all red. We had to keep working, living, so we kiss my mom every morning because we don’t know if we will be back.

That’s no way to live, huh?

That’s how it was. Then sectarian wars started, kidnapping became everywhere. You don’t know who is your enemy, what’s going on, who is in the street?

You were living in fear?

That’s why I’m making a documentary—for now it’s a short documentary, but I’m hoping to get more grants to make a really big film, because there’s so many details—I got a fellowship from Alexa Rose [Foundation].

Congratulations!

Thank you.

You seem in touch with your emotions. Does that help you as an artist?

I think I’m—all of me is emotions, I feel. [Laughter.] People ask “What do you [want] people to get from your art?” I want them to feel something. It doesn’t matter what it is, I’m not directing them, but I want them to meditate with it, to stop and look, and to have feeling.

I remember the first exhibition I had here, 2013, at [Boise State], in the Student Union Gallery, and at the time I had a lot of dark subjects, but very colorful canvases. People came to me and said, “When we look from a distance, it’s so colorful and inviting, then we come and look close and—wow! What? Were you there?” They would see me talking and laughing at the reception, and ask, “How are you like this? With all these things?”.

They thought you couldn’t laugh or smile or joke, with the trauma you’ve been through? You have layers.

Yes, I have all the layers. My personality is—I love to dance, I love to jump, I love to joke, I love to be silly, I love to be a kid. But at the same time, there is this seriousness about what happened to Iraq and what happened to other countries. At the time of wars and chaos, laughter was a mechanism for survival.

Are people here surprised when they learn you are from Iraq? Do they assume you would wear a head covering?

Are people here surprised when they learn you are from Iraq? Do they assume you would wear a head covering?

Oh, yeah. At the beginning, a lot of people would ask me that. I was surprised. I think a lot of people have this stereotype of the Middle East and Iraq, that it is a desert, it’s camels, and it’s women with a burqa.

Do you want to go back and visit?

I do. I’ve been wanting to go. Problem is, it’s so far and expensive. Also I’m scared. I’m scared emotionally of how I would react. Maybe it’s good, maybe it’s bad. Maybe I’ll go and feel like, oh, I need to go again and again. Or maybe I will go, and I will say I don’t want to come here again. I don’t know. As much as I hurt in Iraq, and I have this anger, I also have this nostalgic feeling. It’s so hard when your life gets stolen from you.

Why is sharing your story important?

I want to have our voices heard in a place like Idaho, as someone from the Middle East. I think the story I carry with me is very important. Not only here, but anywhere.

I think sharing your story creates empathy in me, the listener.

Yes. To understand what war does, even if it’s far away from you. A lot of people don’t even know which language we speak. They don’t know anything about Iraq. They know there is a war somewhere, but they have no idea what it is. Most people who came to invade Iraq, even, had no idea what the culture is, and what they left us with. It is important to understand the effect of sanctions; [sanctions] are not hurting the government, they are hurting innocent people. We couldn’t get medications anymore. That word, unhuman—

Inhumane. To share your story and create empathy, could lead to positive change.

Inhumane. To share your story and create empathy, could lead to positive change.

Hopefully.

What would you say to someone who is afraid to share their story?

It’s hard. My sibling, for instance, didn’t want to talk about it. They still don’t. They don’t want to look back on these awful—excuse me—

I—many times, I feel like I’m not someone who loves to be in politics. I love art, I don’t want it to be all about war—but somehow, when I do something beautiful or colorful, I can’t—I feel like I’m betraying—[tearful]

The truth?

Yes—I’m sorry.

I think the truth is pretty important.

It’s good that you took photos before—[laughter.]

West Boise

September 16, 2023

Treefort Music Fest Public Art

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History. The views expressed in this publication are those of the individuals