Creators, Makers, & Doers: Rachael Mayer

Posted on 12/13/23 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History, Edited by HJ Moon & Brooke Burton

Rachael Mayer is a fiber artist who was commissioned by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History to create and install artwork for the Linen District Fence in 2022. Rachael’s skills in sewing, weaving, and quilting have been passed down from mother to daughter to granddaughter. This is a pattern (see what we did there?) commonly found in the tradition of fiber-based craft, the contributions of which have been historically overlooked and undervalued as “women’s work.” With one foot in a community of makers who produce functional and non-functional art objects, and her other foot in contemporary art culture, Rachael strives for balance in the continual practice of accepting the idea that there are many, many, MANY ways to lead a creative life. Her personal work currently explores the inherited ideas around mental health and boundaries. What’s her approach? To come from a place of curiosity, lean into moments of uncertainty, and use her voice to empower. Also, in our convo, Rachael unleashed a cure for burnout. No joke. And sometimes, a knot will untangle itself.

I’m looking around and I see fiber, thread, (and) a loom. If I were to take a guess, I’d guess quilting? But that’s not what you do. What do you do?

I’m looking around and I see fiber, thread, (and) a loom. If I were to take a guess, I’d guess quilting? But that’s not what you do. What do you do?

My practice is rooted in craft tradition, weaving and quilting, but I don’t make blankets or quilts—functional items. I do have a family history of that; my mom is an amazing quilter, my (great) grandmother made blankets for purpose, but nothing I make is something that you’d want to cozy up with. I am relying on those craft traditions and being informed by them, conceptually, which is really important, it’s why I do what I do. It feels like an inherited skill set.

Did someone teach you?

My mom taught me to sew and embroider when I was eight years old. I didn’t really appreciate it, as one does not when they’re eight. But, you know, my mom learned how to sew from her grandmother, who learned from her mother. I use my grandmother’s sewing machine, I have my mom’s quilts all around me, and my dad is a craftsman himself, in woodworking.

Your dad made the bench seat at the loom, which is a work of art, itself.

It is. It’s gorgeous.

Your parents are making functional pieces.

Yes, but if you were to ask them, “Are you creative?” they don’t think so… I disagree. I think creativity is like finding a problem, or an idea around something, and then just failing [at it] over and over again. What I love about the process is, often, that failure sparks another idea, one that’s so much better than the original solution you were seeking. So—yeah, they’re creative.

I agree.

I think if my great‑grandmother were here looking at my work, she’d be, “What are you doing?” She’d have a lot of questions. [laughter].

What kinds of questions?

Cutting up a quilt, or weaving, is sacrilege. Actually, I texted my mom a picture of what’s on my loom right now, and she says, “I just want to talk to you about not cutting it up.”

Oh, it’s a big deal! Are you taking a found quilt and repurposing it?

I’m actually quilting it. I often hand‑paint fabric, then go in and quilt over the top of it. Then I take a big piece of fabric I’ve quilted, and cut it into smaller pieces.

So the quilt you’ve worked so hard on, for hours and hours—just as your mother did—you then proceed to cut up everything you made?

[Laughter.] Yes.

I can see her concern. [Laughter.]

Exactly. It’s a hard thing for real traditionalists to understand. And I get that.

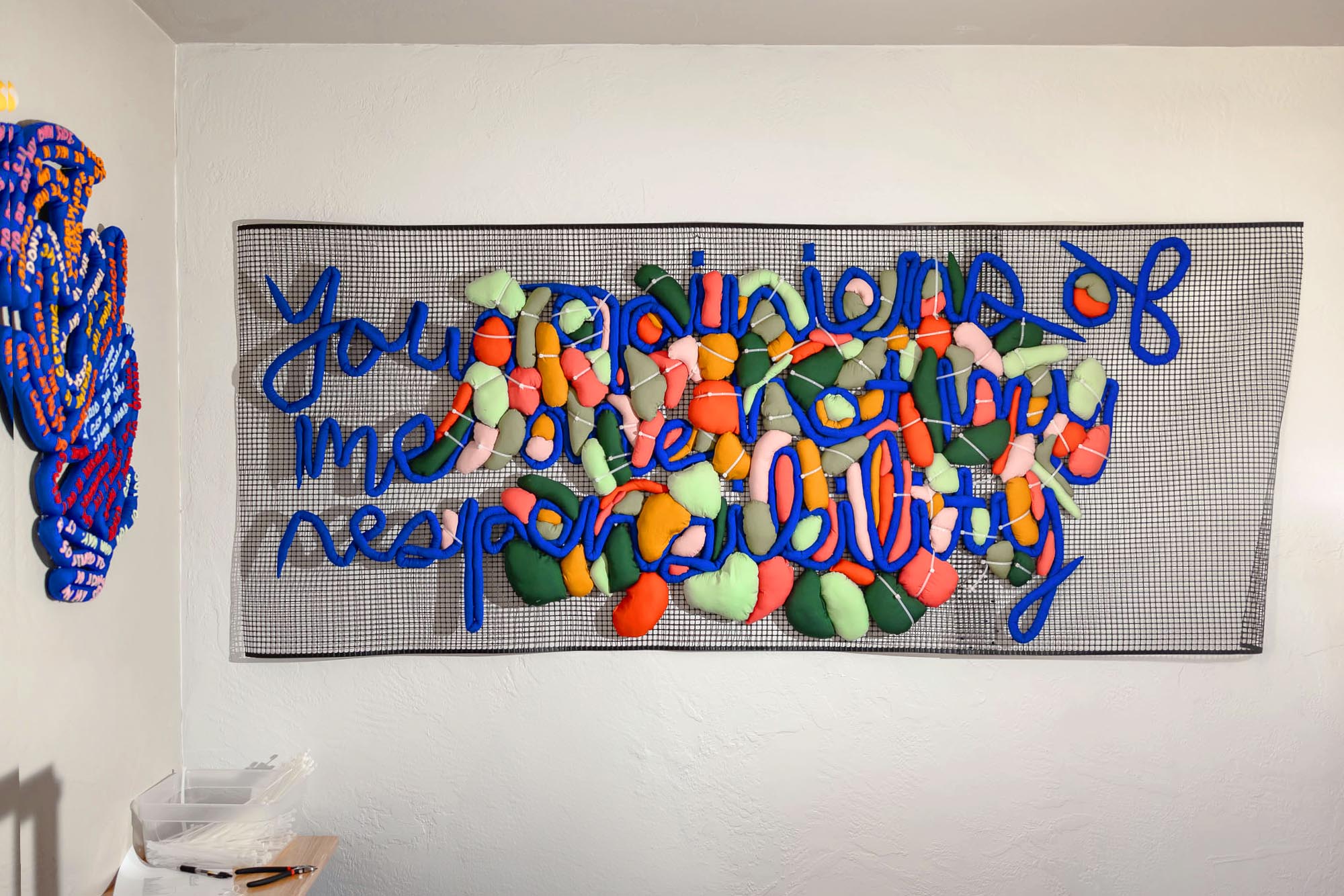

The large work on the wall, the one that says the phrase, “Your opinion,” tell me about it. The tube shapes remind me of kindergarten, using play dough to roll out ‘snakes’. What does is say?

Oh, yeah. “Your opinions of me are not my responsibility”.

Those snake shapes used to be fabric; a two-dimensional surface, which you’ve sewn and stuffed, then made into text, like handwriting. In formal art terminology: you are transforming a picture plane into a sculpture into a line into words into another picture plane. Whew. I’m tired.

Yes, I know, right? [Laughter.] Someone once told me they can tell it’s my work because it looks like it took a long time, which I take as a compliment. But I argue that even things that look simple, can take a really long time.

Are there misconceptions about textile art?

Sometimes there’s a lack of value placed on textiles. We could talk for hours about how “It’s a woman’s craft,” and about how women’s work has been undervalued historically. Fabric is something that’s part of our everyday lives; there’s a cliché about textiles: “When you’re born, you’re wrapped in fabric, and when you die, you’re wrapped in fabric.” It’s really a part of every single stage of life. And, archaeologically, [textiles] often decompose the fastest, so we don’t always have a great record.

Disintegration? We should talk about the Linen District fence project!

I love that piece because I created it to be interactive—for folks to touch it as they go by.

It’s not behind glass, or out of reach?

So often, it’s like, you go into a gallery—don’t touch anything. I respect that, but there’s something about textiles that really invite you to touch. I love that interaction from people, and also from the environment; that [the work is] faded and changing.

It’s being degraded by UV light, the fastest way to disintegrate material, I think. Maybe? I am a scientist.

Yes, as am I. [Chuckling].

Coupla’ scientists here. Okay, back to disintegrating art. We want art to, in the very least, outlive its maker?

The idea of conservation, that it has to be archival, it has to last forever.

Forever. Capital “A” artwork, ideally should outlive its collector and be passed down from generation to generation as an heirloom, and to appreciate in value many times over.

Exactly, yes.

Aha, just as quilts are passed down as heirlooms.

They are indeed. But, if you have a quilt that’s been passed down as an heirloom, it’s in rough shape, it’s been used. It’s softer in some areas— stitches are pulling at fabric; batting gets a bit lumpy if you wash it too many times…

What is your work about?

My work is shifting right now. At its core, it’s around ideas about what gets passed down. Whether it’s skills like quilting and weaving and stitching or—the things passed down through family like body image issues and mental health. And not just by family, but also by community.

Your internal voice is something passed down.

I’m thinking a lot about inherited ideas. I enjoy mixing these bright, happy colors with something more serious or subdued. I think that’s true of anything inherited—we inherit the good with the bad. It can look happy and shiny on the surface, but there’s always something else going on there. I have a great family, but even then, you know, we all do things that, kind of, mess each other up. I’ve been exploring this idea of tension. Fiber is so soft and I have all these stuffed forms that are cushy, but then they’re tied in knots or twisted around. My friend calls them candy pretzels, and that brings me a lot of joy to think of them that way.

Tell me about the works tied in knots. Are they sailor knots, or . . . ?

I tried really hard to do actual knots people could recognize, and it just turns out that is not my skill set, so—

So they’re your own?

Yeah, so, I make them up. Sometimes I tie them, and I’m like, “Oh, my God, I’m never going to be able to recreate this,” or “I don’t know why this [knot] is staying [tied] the way it is.” Some of them are very temporary, too, they’ll fall off the table and suddenly unwind.

It’s like when I get very stressed about a problem and then it suddenly solves itself, without any work on my part. We create plenty of problems for ourselves don’t we?

I always had in my head that I wanted to be an artist in a certain way, or that I wanted to live a certain type of creative life. One thing I am constantly learning and having to reteach myself is that there are so many different ways to exist as a maker.

And as a human.

And as a human. It gets to shift and change. Had we talked a year ago, I’d have had different answers to questions. Three years ago would have been completely different.

What is a change you’re excited about now?

Pre pandemic, I didn’t use a lot of color, or the colors were subdued; a lot of different shades of white and—

Oh, Museum colors. [Laughter.]

Museum colors, sophisticated. I think I felt like [my work] would be more acceptable, whereas vibrant, clashing colors felt a little more kitschy…

Kitschy is a big risk if you want to be taken seriously by people who hold power in fine art institutions.

Absolutely. But during the pandemic I was, “Who am I? What am I doing?” I think we all have that shared collective memory, even if we were doing different things at the time. I was like, “Well, I have a bunch of white yarn, and I have a bunch of dye…” so, I dyed yarn in my bathtub every night, without a plan, which is super odd for me because I love plans. At the end of it, I ended up with all this yarn and all these different colors. And combining those colors…I don’t know…just releases something in my brain. It just makes me so happy.

We talked earlier about the idea of limerence. You have limerence for color and I have limerence for shiny. You’re excited about your new color palette?

I’m really excited; and also about the different color combinations. That’s what’s really exciting about textiles—you get to mix colors. If you’re a hard‑core dyer, you can mix any sort of dye color you want. What I’ve really been enjoying is taking all this yarn that I dyed years ago, and seeing how the colors play off of each other. It’s almost like pointillism. Impressionistic. It offers a whole new way to think of color, but with constrictions. But it is super interesting because of those constrictions.

What are some of the challenges that you’ve faced in your creative journey?

Um, yeah…

The energy in this room just went way down. [Laughter.]

Yeah [laughter]. It’s tough. I mean, I think there are opportunities you lose out on; that really feels like a challenge. I was up for a huge commission in 2020. Then, “How do we COVID clean textiles?” We were just learning about the virus, so we didn’t have answers for that. I lost a $70,000 commission. It would have been totally life-, and career‑changing.

Oh, that’s crushing. I’m so proud of you for getting the commission in the first place, I want to honor that. And, while it is a large sum, it certainly reflects the artist’s large amount of creativity, time, and dedication.

I love thinking about time. I’m also constantly frustrated about time, always wishing I had more. But what’s so cool about time—it’s one of those things you give away, that you don’t get back, ever. We all have a finite amount of it. I think that’s what’s so special about it, too. It feels like, if you only have so much time and you’re putting it into this object; then, there’s got to be something there. I don’t know what I’m trying to say—

I think the energy transfer of time, care, and positive attention into an object will create value, not in a tangible way, but it’s there. And that value will have a positive effect somewhere, somehow. That kind of value?

Yeah, exactly.

What are some positives to balance out the struggles?

Hmm. When I think back over, even just a few years, I’m really proud of the flexibility I’ve had. That commission fell through in 2020—I was, “I need to make money as fast as possible.” So I started doing craft fairs and making smaller objects that are more accessible.

Something at a price point for everyday people?

Yes, and something to buy without needing a 12‑foot wall to put it on. I had amazing conversations with random people who I never would have met [otherwise] and created a community out of all these makers who also do the whole slog of the craft fair. My work shifted for a few years, I wasn’t doing as much conceptual work and I was really missing it. I do fewer craft fairs now; I’m able to focus more on the conceptual side. That flexibility is something I’ve had to pull out of myself. It’s difficult to do because I don’t like it, but at the same time I crave it. I think I have a hard time with uncertainty, but I also recognize that in those moments of uncertainty are the best ideas I’ve ever had.

Creative problem‑solving?

Failing over and over again is uncomfortable, but worth it. [For] anyone in a creative field where you are your own boss, you’re trying to make money, an income, and a livelihood off your creative products, that puts a lot of stress on the creative process itself.

Does it compete for energy?

It can totally compete for energy. There are times in my career where I’ve thrived off that; then there are other times where, I’m like, I’m really tired. I need a moment, a hibernation moment, to be able to sit with my feelings and ideas and fail a lot in the studio.

What does a hibernation period look like for you?

It becomes very introspective. Lots of deep thinking and journaling; it becomes a meditation of sorts. Sometimes, when I’m really into quilting, or deep into a weaving, and I’ve memorized my pattern—I know exactly what I’m doing, I forget to—I need to set timers to remember to drink water because I just become so obsessive.

Your body is moving, but your mind is free?

It’s totally free, and I get to think about a lot of things. Or, sometimes I don’t want to think about anything, I listen to an audiobook or something. So, I think that hibernation period for me is turning my brain off a little bit.

I don’t know if this is of interest to you, but I know a lot of artists struggle with the business side. Do you have lessons there?

One thing I really value, that I think is pretty common especially in craft fields, is collaboration and collective problem-solving. When I have a question about a pattern or something… there’s this community [available,] figuring out patterns or issues or whatever, and not being gatekeepers of knowledge.

What is a gatekeeper of knowledge?

I think that it’s really hard to do what we all do, there’s a balance between you need(ing) to figure it out for yourself, but also, if you know something that is going to substantially change someone’s life or going to help them in some way, within the craft world, I’m going to share every single part of my process with you so that you can recreate it, which I think has roots in craftsmanship.

For instance, quilting circles, one work made by many.

Yeah, quilt circles are a great example of that. I think people are more likely to share advice and all the failures they had. And that doesn’t mean that you, yourself, are not going to fail. But it’s really helpful to be open and honest. I think sometimes within whatever field you’re in, there’s this idea that there aren’t enough seats at the table. That it’s too crowded, and you have to fight to stay at it. What I really love about crafts is, it’s like, “No, we can just make a bigger table.” And that, to me, feels so much better. I had quite a few mentors. It’s awesome how easy it is now to connect with folks who are far away. I have great mentors based out of California, or on the East Coast, or across the world, who are able to give advice on how they’ve made it work. I think also reminding yourself that just because it works for one person, doesn’t mean it’s going to work for you. It goes right back again to [the idea that] there’s more than one way to live creatively. There’s so many different ways to exist.

In many fields, especially in art, there’s a great deal of value placed on originality and having a unique personal voice. Is that related to gatekeeping knowledge?

It’s a hard question. My approach to that within my own practice is to always come from a place of curiosity. Even within quilting or weaving, there are only so many combinations—how you put things together, or common quilt patterns. We could all do a bear paw pattern, or we have the northern star—these different patterns that have been the same across hundreds and hundreds of years. If we go back far enough, our ancestors were stitching or they were weaving. It’s this commonality that we all have. In terms of originality—I don’t want to ever make someone feel like I am copying them in some way. But also within quilting, again, I’m doing the same patterns.

Tricky.

But when I approach something out of curiosity, I want to know more about it, and I want to figure out how it connects to me. Once I’m curious about something and I’m curious enough to create some version of it, then it becomes connected to me conceptually. Because I’m changing it. Because I have a curiosity for it.

And you have your own perspective, your own history, and your own future that cannot be duplicated.

Exactly.

Has there been feedback on your art, or reactions to it that were unexpected?

I’m always surprised and delighted when younger people, children, interact with my art, especially if I’m there and I tell them they can touch it, or tell them they can put their face on it—

I would do that.

—because we easily forget that, especially when artwork is up in galleries. [The work] can have this really physical connection. We all know, for the most part, what a quilt feels like. Even though we know what it feels like, [knowing is] different than actually, physically touching it. I love that moment where they touch it.

The look of surprise, curiosity, or pleasure?

Yeah, exactly. But, this piece where all the rope is spelling out, “Your opinions of me are not my responsibility.” It’s really heavy, you wouldn’t think so because it’s all stuffed forms.

Let’s talk about that one, the text is written in first‑person narrative, There is a “you” and a “my.” Some of the text in this room I see as affirming to the viewer and some of it I suspect can be challenging. What would you call it? It’s not aggressive, but it’s—

—like erecting boundaries. Text in my work is a new thing, it’s exciting. It’s influenced by creating marketable items for craft fairs; putting quippy sayings on embroidery hoops. It’s the other part of my practice. What I’ve always wanted to do is to be affirming and empowering, and also remind us to have those boundaries we that need. It felt really natural to start incorporating that into my conceptual work.

Especially when I was younger, I was so concerned with how I was perceived by others, or wanting to be gentle and soft and not confrontational… make myself smaller so it wouldn’t inconvenience other people. As I have gotten older, I have gone the complete opposite. Now, I’m coming back to what feels more balanced. That piece in particular is clearly communicating a boundary, but it’s also all these soft forms; I love that. It’s also kind of hard to read; you kind of have to work for it, to read it.

For our readers, Rachael literally just watched me do this. I looked at the work, and you, Rachael, watched me attempt to sound out all the words. And it took two… eight minutes?

For our readers, Rachael literally just watched me do this. I looked at the work, and you, Rachael, watched me attempt to sound out all the words. And it took two… eight minutes?

Yeah, yeah.

I read out what I thought it says, then I had to go back and make corrections. Was watching me work at it fun for you? [Laughter.]

It was. I did give you a hint on one word because I was, like, “I can’t let Brooke do this any longer.” [Laughter.] But I love that it is this firm sentiment. Yeah, it’s kind of camouflaged; these fluffy, organic forms are not—

It’s too pretty and colorful to be aggressive.

It’s a gentle opportunity.

I agree. It’s an honorable, gentle opportunity for me. Maybe for you too.

I think a lot of my work right now is dealing with mental health and thinking about the expectations I have of myself that other people do not have of me. There’s almost this idea of aspiration fatigue. You know, we talked about time and how I often feel like I never have enough time, and if I just had more time I could do all these things and reach all these goals.

But, when I reflect back on my career thus far, there have been so many opportunities. Two years ago I would have never assumed I would be making a quilt for the Linen District fence. There are unexpected opportunities and problems to solve. As many times as I say “There are so many different ways to live creatively,” that is still a constant practice I try embody.

If aspiration fatigue is a barrier to creative practice because it sucks energy…now what?

What I hope is that there’s a reprieve and a little hibernation of just making and existing; see what comes from that.

Goin back, you were remembering and celebrating past opportunities and problem solving, things that you didn’t appreciate at the time because you were too busy aspiring.

Oh, my God, that’s literally, I think, almost word for word what is on that little twisty blue snake with all the words cut out.

What does it say?

“What could we do if we didn’t get in our own way? What could I do if, instead of disparaging all I didn’t do, I was proud of what I have done?”

Thank you.

West End Boise

December 15, 2023

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History. The views expressed in this publication are those of the individuals